full list of every character in The Yellow Wallpaper & who they are — narrator, John, Jennie, Jane, Mary, baby, brother, mother, cousins & Weir Mitchell!

go here if you just want a summary of The Yellow Wallpaper

and here for the full text of The Yellow Wallpaper

Our unnamed protagonist is the narrator of the story “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” a short story published in 1892 by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which uses the conceit that the protagonist is writing the entire story in a journal. The protagonist is a middle to upper class mother of a young baby; the woman either works as a writer, or writes extensively enough that she considers it her life’s work.

The protagonist is a writer who not only doesn’t have “any advice and companionship about [her] work” but is treated by John’s sister, Jennie, as though “it is the writing which made [her] sick!”

Suffering from a “nervous depression” in the opening of the story, the protagonist’s husband, John, brings her to an old country estate to take the “rest cure”, which as the protagonist describes it involves “tonics” “air” and “exercise” as well as an injunction not to work or visit friends—to do anything stimulating.

Over the course of the story, our protagonist becomes more and more convinced that being isolated and bored (primarily in a room with hideous wallpaper) is in fact exacerbating her mental breakdown, but she’s not able to convince her husband of the fact.

John is the protagonist’s husband, a physician who thinks he knows how to cure his wife. He will, unfortunately, turn out to be dead wrong about that.

John is an ordinary husband. He expects a wife of the times, when what he has instead is a flighty, intellectual, easily bored companion who craves his respect. As the story goes on, John increasingly spends days and even nights away from home. Our protagonist is convinced that he’s treating serious cases the whole time, though he could also be avoiding his increasingly unstable wife (and perhaps a room with yellow wallpaper in it). John “has no patience with faith, an intense horror of superstition, and he scoffs openly at any talk of things not to be felt and seen and put down in figures.” This is his fatal flaw. Because he can’t measure his wife’s deterioration, it doesn’t exist—even if she tells him she’s getting worse and not better.

After spending much of the story begging to have her opinions heard, our protagonist finally gives her husband up for lost, and turns her full attention to the mystery of the wallpaper. As she is truly slipping into her delusions late in the story, she describes the situation with John thus: “I really do eat better, and am more quiet than I was. John is so pleased to see me improve!” Because she’s playing the part of the perfect wife outwardly—and better than she probably ever did before her illness—John thinks everything is fine. And no wonder he would thinks so; he has no respect for her interiority.

Still, he does love her, and puts these strictures on his wife out of love, erroneously thinking that he can make her be exactly what he wants without destroying her utterly.

“My brother is also a physician, and also of high standing,” our protagonist explains at the beginning of the story, “and he says the same thing [as John]”, convincing friends and relatives that she isn’t sick, despite the protagonist’s gut feeling that she is in fact suffering something real. Instead her husband and brother would agree that she’s just suffering from “a slight hysterical tendency”, excess of “imagination” and a number of “fancies” about her own condition.

The protagonist can’t rely upon her brother, and knows it. When thinking about the possibility that she might have to visit another doctor, she confides, “I had a friend who was in [Weir Mitchell’s] hands once, and she says he is just like John and my brother, only more so!”

“John says if I don’t pick up faster he shall send me to Weir Mitchell in the fall,” says our protagonist. “But I don’t want to go there at all.” Weir Mitchell was a real-life physician and author (1829-1914) who popularized the “rest cure” that our protagonist is suffering through. The rest cure’s basic idea is to treat a disease or other malady by going to a good environment (normally, away from the smoke of the city to a place such as a coast, mountains or other rural area) and then isolating, resting and relaxing away from the stresses of ordinary life.

“It is fortunate Mary is so good with the baby,” our protagonist says. Presumably, Mary is a wet nurse for the infant. Wet nursing was a common practice at the time among all social strata.

“It is fortunate Mary is so good with the baby. Such a dear baby! And yet I cannot be with him, it makes me so nervous.” Our protagonist seems to care about her baby and yet be terrified of him at the same time—either because she feels she doesn’t know how to care for him and feels out of her depth, or perhaps because the baby seems to symbolize to her a future as a full-time mother and homemaker, which she never wanted. The protagonist is ambivalent about her child, who exists more as an idea of a child than as an actual baby. She’s never around him and so never gets to know him at all.

“There’s one comfort, the baby is well and happy, and does not have to occupy this nursery with the horrid wallpaper. If we had not used it that blessed child would have! What a fortunate escape! Why, I wouldn’t have a child of mine, an impressionable little thing, live in such a room for worlds. I never thought of it before, but it is lucky that John kept me here after all. I can stand it so much easier than a baby, you see.”

Our narrator is isolated in what might have, in another time, been a nursery; and though she is not the baby she’s being effectively infantilized: not only is she not allowed to take care of her own child, her movements are restricted by others, she has to ask for everything she wants—and no one will allow her any of it, and she’s treated as though she doesn’t know her own mind. For instance, she’s referred to by her husband as a “blessed little goose” as he treats her whims with the same patronizing disdain as parents tend to unfairly treat children. To make sense of her situation, the protagonist spins it so that her being in the yellow room is a way of protecting her child from a worse fate; the only way she can “protect” him when she isn’t even allowed to interact with the baby.

“Well, the Fourth of July is over! The people are gone and I am tired out. John thought it might do me good to see a little company, so we just had mother and Nellie and the children down for a week.”

‘Mother’ presumably refers to the protagonist’s mother, though it could also refer to John’s mother. Nellie is probably a caretaker for “the children”—though she could also be the children’s mother. We are never told who the children belong to, or what the exact relations are here.

“I tried to have a real earnest reasonable talk with [John] the other day, and tell him how I wish he would let me go and make a visit to Cousin Henry and Julia,” our protagonist admits. But John won’t let her. John does hold up seeing them as a reward for good behavior though, knowing how much it matters to her:

“When I get really well John says we will ask Cousin Henry and Julia down for a long visit; but he says he would as soon put fire-works in my pillow-case as to let me have those stimulating people about now.”

Henry is probably the protagonist’s cousin, although he could also be John’s cousin. Julia is probably Henry’s wife, although it’s also possible she could be a blood relation, like an unmarried sister. Either way, this is the family that our protagonist shows the most enthusiasm for in the story, obviously enjoying their company. Why? Well, John described them as “stimulating people” so presumably they’re people our protagonist can talk with, laugh with, and possibly read and discuss writing with.

“There comes John’s sister. Such a dear girl as she is, and so careful of me!,” our protagonist writes. “I must not let her find me writing. She is a perfect, and enthusiastic housekeeper, and hopes for no better profession.” Jennie is John’s sister, and she’s the woman our protagonist “should” be. This puts some tension between them, as our protagonist feels like she can’t rely on Jennie or trust her. And yet Jennie has more depth than our protagonist wants to admit.

Jennie increasingly does all the work around the house as our protagonist slips into depression, and our protagonist is resentful of it, even as she is grateful. The best thing our protagonist thinks about Jennie is that Jennie will leave her alone when she wants to be alone.

Jennie seems to realize that our protagonist is not getting better over the course of the story, though she may not know why. Near the end of the story our protagonist says “I heard [John] ask Jennie a lot of professional questions about me. She had a very good report to give. She said I slept a good deal in the daytime.”

Although our protagonist describes this as a “good report” it seems clear that Jennie has noticed something is wrong. Either John hasn’t noticed, or he has, and asks a lot of questions because he wants a second opinion. Our protagonist says after that “John is to stay in town over night, and won’t be out until this evening. Jennie wanted to sleep with me—the sly thing! but I told her I should undoubtedly rest better for a night all alone.” Whether this was Jennie’s idea or John’s, Jennie knows our protagonist is not doing too well, but is persuaded to leave her be—this is in fact her defining trait. She doesn’t push her own opinions, she’s persuadable.

The closest Jennie ever gets to being really forthright is late in the game when she’s staring at the wallpaper: “She didn’t know I was in the room,” our protagonist describes, “and when I asked her in a quiet, a very quiet voice, with the most restrained manner possible, what she was doing with the paper she turned around as if she had been caught stealing, and looked quite angry—asked me why I should frighten her so! Then she said that the paper stained everything it touched, that she had found yellow smooches on all my clothes and John’s, and she wished we would be more careful!”

Our protagonist may be right that though she’s the only one interested in the wallpaper, “John and Jennie are secretly affected by it.” In fact, the pigments used in green and yellow wallpaper contained arsenic, and there were known cases of poisoning from ingesting wallpaper. It’s entirely possible that Jennie was worried not just about the state of their clothes.

The night before they’re supposed to leave the country estate, our protagonist starts ripping the wallpaper off. In the morning, when Jennie comes in, “Jennie looked at the wall in amazement, but I told her merrily that I did it out of pure spite at the vicious thing,” our protagonist says. “She laughed and said she wouldn’t mind doing it herself, but I must not get tired.” Whether or not Jennie thought the wallpaper was nefarious, she obviously hated it too. And yet our protagonist missed this information, since the two never really talked or interacted.

This infamous character exists in only the second-to-last line of the story, as our protagonist has made her break with reality and truly become the creeping woman. “‘I’ve got out at last,’ said I, ‘in spite of you and Jane! And I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t put me back!'” the protagonist writes. This “mistake” has collected a lot of interest over the years. Is Jane supposed to be Jennie? Mary? The narrator and protagonist herself? Whoever she is, she’s spent the story trying to keep the creeping woman behind bars, at least in our protagonist’s mind. In that sense Jane could be any one of the female characters in the story. Still, it’s interesting to remember at this crescendo that our protagonist is still writing this story, and whoever Jane is, she’s probably named purposefully here.

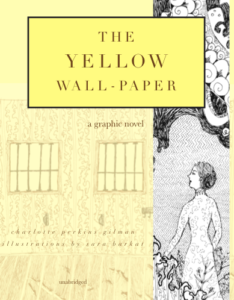

The Yellow Wallpaper characters list by Sara Barkat.

Read The Yellow Wall-Paper summary

Read Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s essay Why I Wrote the Yellow Wall-Paper

Read How to Do Literary Analysis: An Experimental Reflection Based on the Yellow Wall-Paper

Read a poem by Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Fire with Fire

______________________

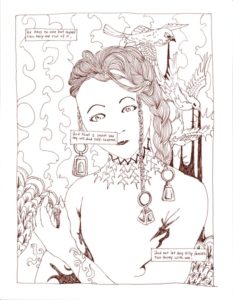

“Sara’s stunning, heartbreaking, and relevant illustrations help to tell a difficult, haunting story. I will return to the story, as I do with all those stories I love, again and again.”

—Callie Feyen, teacher

The Yellow Wall-Paper: A Graphic Novel Writing Series

Prompt 1-Out of One Window I Can See