Photo by William Topa on Unsplash

The Political Nature of War in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness

In The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin argues that war is primarily a national phenomenon, a product of fear; as opposed to a human activity dictated by biology. To do so, she creates a detailed study on the cultural preconditions of war, through the example of the dispute on Gethen, and how this plays out in Karhide.

In “The Question of Sex”, through the character of Investigator Ong Tot Oppong, Le Guin sets up two early possibilities for why the Gethenians don’t have war, the first being that it is because of their biology—that, as Oppong wonders, continuous sexual capacity and organized social aggression may be linked, or that war is a product of the masculine against the feminine. The second idea is that the weather on the planet is so cold and inhospitable that it gives no opportunity for war. “The dominant factor in Gethenian life … is their environment … Here man has a crueler enemy than even himself.” [96] Though the Gethenians have never yet experienced war, they come very close to doing so in the course of the novel—and by setting the Gethenians up as biologically different from humans, without a gender divide, and yet playing out the familiar patterns leading to war, Le Guin takes ammunition away from both the argument that war is a natural or necessary human activity, and the argument that it is a gendered activity.

It seems apt at this moment to point out that when Le Guin or her protagonist Genly Ai talk about war in The Left Hand of Darkness, they are referring to modern warfare. In our own history, war has evolved to become what it is today. Le Guin—rejecting the biological explanation—takes on the question of why. What are the cultural preconditions for war?

Well, usually there is a real dispute to start. In chapter one Estraven explains the quarrel that is at play between both nations. There is a border dispute; Karhide had recently taken land from Orgoreyn, but the decision was never recognized by Orgoreyn. Estraven explains that he has “been helping some Karhidish farmers who live in the Valley to move back east across [it], thinking the argument might settle itself if the Valley were simply left to the Orgota, who have lived there for several thousand years.” He further explains, “I … got to know some of those farmers. I dislike the thought of their being killed in forays, or sent to Voluntary Farms in Orgoreyn. Why not obviate the subject of dispute?…But that’s not a patriotic idea.” [15] The difference traced out here—between caring about other people, and being patriotic—caring about the idea of country—will turn out to be of immense importance to Le Guin’s argument, and she will come to focus particularly on patriotism as a negative, national ideology that leads to the possibility of war.

Late in the book, Le Guin’s character, Genly, says “I remembered Estraven’s comment … when I had asked him if he hated Orgoreyn; I remembered his voice last night, saying with all mildness, ‘I’d rather be in Karhide…’ And I wondered, not for the first time, what patriotism is, what the love of country truly consists of, how that yearning loyalty that had shaken my friend’s voice arises: and how so real a love can become, too often, so foolish and vile a bigotry. Where does it go wrong?” [279] This question is one the novel answers, at least in part, through the process of example. Le Guin shows, in Karhide, the emergence of a nation-state and a national mindset. But in this quote she also touches on some of the answers to this very question. There is a real, essentially human thing that exists behind and before the idea of patriotism—that is love of one’s homeland, loyalty to the place you belong. But somehow, this “real love” becomes a “foolish and vile … bigotry.” How?

What causes patriotism? In an early conversation between Estraven and Genly, Estraven brings the idea to the fore in the novel for the first time. “Let me ask you this, Mr. Ai:,” he says. “Do you know, by your own experience, what patriotism is?” “No,” Genly answers. “I don’t think I do. If by patriotism you don’t mean the love of one’s homeland, for that I do know.” Already, patriotism is being differentiated from love of homeland, and Estraven’s answer will lead to a clearer definition: “No, I don’t mean love, when I say patriotism. I mean fear. The fear of the other. And its expressions are political, not poetical: hate, rivalry, aggression.” This, then: patriotism is in fact the opposite of love of homeland—it is fear of everything else. And, Estraven believes, this fear leads to hate, and that hate to aggression—to war. He continues, speaking of Karhide’s political situation, “It grows in us, that fear. It grows in us year by year. We’ve followed our road too far.” [18] He will then go on to compare this impulse to the message Genly brings, of the coalition of the Ekumen, a peaceful, interplanetary federation—the “new road.” This adds evidence to Le Guin’s argument that the state of war is not biological, natural or necessary. It is a road, an option. And there is another road.

Later in the book, Genly describes the general feeling in Karhide after Tibe becomes regent. Genly notices the reaction to one of Tibe’s speeches where he talks about Karhidish farmers, “brave… true patriots” who had (of their own accord!) gone across the border, attacked and burned a nearby Orgoreyn village, killed nine people and dumped their bodies in the river. “‘Such a grave,’ said the Regent, ‘as all the enemies of our nation will find!’ Some people looked grim as they listened [to the radio reports], others uninterested, others satisfied, but in these various expressions there was one common element, a little tic or facial cramp that had not used to be there, a look of anxiety.” Here, Genly pinpoints the fear Estraven talks about that is the root of patriotism.

And Tibe, through his broadcasts, through his vilification, is drumming up fear on purpose. Tibe talks “… in a ranting, canting, emotional tone that went shrill with vituperation or adulation.” Part of how he is creating fear is through the choice of words, part is through the extremity of expression. He is not talking politics, he is talking emotion. Genly adds, “[Tibe] talked much about pride of country and love of the parentland, but little about shifgrethor, personal pride or prestige.” Here, Genly marks the fact that Tibe is trying to draw people together in a national mindset of love for Karhide, hate of Orgoreyn, a sort of mob mentality that plays up the collective emotions of many people and brings them in line with each other, while ignoring personal, individual emotion. Genly decides that “[Tibe] was deliberately avoiding talk of shifgrethor because he wished to rouse emotions of a more elemental, uncontrollable kind. … He wanted his hearers to be frightened and angry. His themes were not pride and love at all, though he used the words perpetually; as he used them they meant self-praise and hate.” [100-101] This patriotism, this national mindset, this fear, as Estraven describes it, depends on seeing the other side as “the enemy”. And all of these things, though they play out in action, begin in the realm of ideas.

It is through the use of political ideas and modes of thinking that the national mindset is created, Le Guin is saying here. More than that, through drawing upon fear, it creates the enemy—and when there is an enemy, you have the possibility of war. It is a clear path she’s tracing here, and there is a definite cultural/political cause… it is not biological. Aggression is biological, fear is biological, but organized aggression, acted out against an enemy chosen by the state—in other words, war—is not.

The characteristics of nationality that lead to the possibility of war is caring about borders, having a sense of national identity, and having a civilization capable of being mobilized—both technologically and ideologically. In chapter five Genly observes, “Orgoreyn … had become … an increasingly mobilizable society, a real nation-state. [If Karhide became] a nation instead of a family quarrel … [became] … patriotic … the Gethenians might have an excellent chance of achieving the condition of war.” [49] Here, again, the condition of war is connected to a type of social organization; a nation-state, a patriotic, mobilizable entity.

Karhide is a monarchy—but it is in some important ways less centralized, less absolutely controlled, than the more “progressive” civilization of Orgoreyn. It runs on ancient ideas of hospitality (a social institution, and an individual one) and oral storytelling. “The seeming nation,” Genly explains at an earlier point in the novel, “unified for centuries, was a stew of uncoordinated principalities, towns, villages, ‘pseudo-feudal tribal economic units,’ … vigorous, competent, quarrelsome individualities over which a grid of authority was insecurely and lightly laid. Nothing, I thought, could ever unite Karhide as a nation.” When he considers how the Ekumen must appeal to them, he says “[it] could not appeal to these people as a social unit, a mobilizable entity rather it must speak to their … sense of humanity, of human unity.” [99] Here, against the mobilizable entity, the nation-state, comes another concept, that of human unity. Inclusive, instead of exclusive; individual instead of collective.

But Tibe, as Regent, uses the ability of mass media—language, propagandized, to influence people’s ideas, to create that exclusive collective ideology necessary for the state of war. He speaks on the radio, “praises of Karhide, disparagements of Orgoreyn, vilifications of ‘disloyal factions,’ discussions of the ‘integrity of the Kingdom’s borders…’” [100] These are all about creating a national identity. The concern about borders—the idea of loyalty to a nation, instead of to a person [248], family, or clan—the talk that makes Karhide out as good and Orgoreyn as terrible. The quote goes on. “…lectures in history and ethics and economics.” Again, the subjects here are being created to support the idea of a nation—a nation has a national history, a history curated by the nation.

But the change to nation-state is caused by more than just the radio. In fact, the change had already been occurring, it had to have been, or Tibe would not have been able to draw the people together. Genly observes, “Slow as their material and technological advance had been, little as they valued ‘progress’ in itself, they had finally, in the last five or ten or fifteen centuries, got a little ahead of Nature. They weren’t absolutely at the mercy of their merciless climate any longer; a bad harvest would not starve a whole province, or a bad winter isolate every city.” [101-102] This ability—to have larger, lasting connections to different places, and to live above subsistence level, are a prerequisite for nationhood. Le Guin adds to this idea through the observations of Oppong, who writes, “the marginal peoples, the races that just get by, are rarely the warriors.” [96] Why? This seems to be based on a combination of things. Ease, connectivity, yes. But also a change in mindset that comes from being “a little ahead of Nature.” Perhaps an exaggerated idea of your own importance in the world, or a furtherness from the awareness of death [70], an idea that nature can be controlled—and maybe, from there, that people can be controlled.

Genly says, of Tibe, “He was after something surer, the sure, quick, and lasting way to make people into a nation: war.” [102] Why is it lasting? Because it is unifying. The unification leads to war, the war to unification. “The number of Palace Guards and city police on the streets of Erhenrang seemed to multiply every day; they were armed, and they were even developing a sort of uniform. The mood of the city was bleak, although business was good, prosperity general, and the weather fair.” [102] Here, already, you see some of the changes being wrought. Yes, Tibe is influencing people, but it is the people who are “develop[ing] a sort of uniform”—who are, in other words, becoming an army. It is the people, the farmers who, spurred to action, are attacking Orgota villages… and Tibe is spinning it, driving up a frenzy of fear of the other, of what is outside the borders.

“[Tibe] talked a great deal about Truth also,” Genly says, “for he was, he said, ‘cutting down beneath the veneer of civilization.’” The idea of “cutting down beneath the veneer of civilization” is a call to a more natural state—it is the idea that all this talk, enemies and war, is Truth—might, in fact, be a kind of biological, necessary human action. But Genly continues, “Of course there is no veneer, the process is one of growth, and primitiveness and civilization are degrees of the same thing. If civilization has an opposite, it is war. Of those two things, you have either one, or the other. Not both. It seemed to me as I listened to Tibe’s dull fierce speeches that what he sought to do by fear and by persuasion was to force his people to change a choice they had made before their history began, the choice between those opposites.” [101] Here, Le Guin calls to attention the danger of believing something like war to be natural and necessary. “By fear and persuasion” she says—not by logic, or truth—Tibe was trying to force his people to “change a choice they had made.” Again, you see the two roads, with the emphasis on choice. War, Le Guin is saying, is a choice, but it is one made through fear. The danger Tibe presents, specifically, to Karhide is that he may be able to fool the people into forgetting that war is a choice.

Estraven and Genly later have a conversation that seems to encapsulate Le Guin’s reflection on the difference between love of homeland and patriotism-fear-hate, and the arbitrariness, the politically-motivated nature of the whole conception of the nation-state. In return to Genly’s question, Estraven asks:

“Hate Orgoreyn? No, how should I? How does one hate a country, or love one? Tibe talks about it; I lack the trick of it. I know people, I know towns, farms, hills and rivers and rocks, I know how the sun at sunset in autumn falls on the side of a certain plowland in the hills; but what is the sense of giving a boundary to all that, of giving it a name and ceasing to love where the name ceases to apply? What is love of one’s country; is it hate of one’s uncountry? Then it’s not a good thing. Is it simply self-love? That’s a good thing, but one mustn’t make a virtue of it, or a profession… Insofar as I love life, I love the hills of the Domain of Estre, but that sort of love does not have a boundary-line of hate. And beyond that, I am ignorant, I hope.” [212]

The line of country, Le Guin deftly draws through her description, is arbitrary. It is not real. It is not the “towns, farms, hills and rivers and rocks,” it is not “how the sun at sunset in autumn falls on the side of a certain plowland in the hills,” it is, in fact, just a line—a line that someone drew with no necessary connection to truth or to individual things. And to draw a line is to deny the possibility of the love of these things wherever you may find them.

If there is a positive theme to this story, and I believe that there is, it is in the ability for individual thought and choice, and in seeing others as individuals instead of enemies—and there is no better example of this in the novel than the story of Estraven and Genly. They are able, despite the lines others have drawn and that they exist within, to view each other, by the end of the book, as human, and despite all their differences, to recognize each other as individuals. This incredible action has not just personal repercussions, but large-scale political ones—through their actions, Estraven and Genly did manage to avert war; through hardship and sacrifice, even if Estraven didn’t make it.

For though humans on earth may be disposed towards war—and Le Guin shows the temptation towards it as a real danger—it is not dictated by biology—there is another road, showed in this book both on Gethen and in the Ekumen, brought together through the power of communication and shared humanity.

—Sara Barkat (2017)

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Left Hand of Darkness. Ace Paperback ed., Ace Books, 2000.

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy this science fiction short story,Brianna

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy this Urula K. Le Guin poetry prompt!

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy this Ray Bradbury Poetry prompt!

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy this Tony Wolk poetry prompt!

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy this article, Strange and Wonderful Worlds: How I Discovered Science Fiction by Glynn Young

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy steampunk art!

If you enjoyed this study of war in The Left Hand of Darkness, you might also enjoy the William Blake Arts and Experience Library!

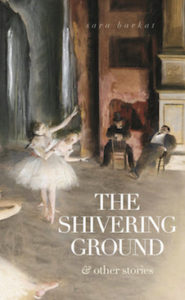

“Stunning…from start to finish. Barkat is a fierce new voice.”