I thought I knew the history of the Civil War. I was wrong.

I was born and grew up in New Orleans, a city saturated with French, Spanish, American, and Black American history and culture. Louisiana law wasn’t based on English common law but on Napoleonic Code. Counties are called parishes. Mardi Gras was an official holiday.

The state was, and to some extent still is, three regions, each with a distinct accent. North Louisiana, where my father came from, resembled East Texas and Mississippi, including the Southern accent. Southwest Louisiana is Cajun country and where my maternal grandfather was born and raised. And then there was New Orleans, with its own distinct accent that sounds vaguely Brooklynese. My mother and her family were all born there, and that’s where I lived with my two brothers.

Benjamin “Spoons” Butler

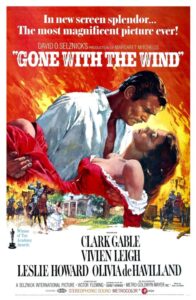

If one subject tied and unified the state of Louisiana, it was history, specifically Civil War history. Long before I took my first history class, I heard about Benjamin “Spoons” Butler and the Union occupation of New Orleans, that Louisiana had had the most expansive and wealthiest plantation system in the South (cotton and sugar cane), and that it was the state’s shame that the first president of LSU had been none other than William Tecumseh Sherman, the Yankee who marched through Georgia. To make sure I understood the Civil War’s origins, my paternal grandmother never called it the Civil War; it was the “War of Northern Aggression.” And my mother’s favorite movie was the one that glorified the Lost Cause — Gone with the Wind.

A century after its end, the Civil War was still very much a part of my family.

Poster for “Gone with the Wind”

In high school, my American history class was the first major step in my re-education, and it had everything to do with the teacher. Mrs. Isenhower was young, brilliant, and came from Indiana (i.e. a Yankee). She taught three classes of senior English and two classes of American history. She was also one of the toughest teachers in the school.

She graded hard. She expected you to keep up with lectures and read the textbook and supplemental reading on your own. And — the key for me — she believed in studying primary historical sources. At the time, every American history class in the state was required to teach six weeks of communism. The recommended text was a newly published book entitled Masters of Deceit by J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI. Mrs. Isenhower said no, she wouldn’t use it, because we needed to know where communism had come from. Our class spent six weeks reading Das Kapital (the abridged version) by Karl Marx, learning the basic ideas envisioned by communism.

T. Harry Williams

Our required research paper for the overall class was one-fourth of the final grade. You could choose the subject, but she had to approve it. I chose the pre-Civil War plantation system, and I spent considerable time in the libraries of Tulane and the University of New Orleans (then part of the LSU system) as well as the largest public library in metropolitan New Orleans — the big library downtown.

My research turned up one surprise after another. Most Southerners never owned slaves; the average price was more than $30,000 in today’s dollars, with a skilled slave (like a blacksmith) costing the equivalent of more than $60,000. A tiny elite occupied homes like Tara and Twelve Oaks in Gone with the Wind; most plantation homes had two rooms and perhaps a porch. Plantation owners themselves worked in the fields. Louisiana, with its sugar cane, likely had more famous planation homes than most Southern states. They lined the River Road on both sides of the Mississippi from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. But these operations were nowhere close to it.

Over the years, I occasionally read Civil War history, but it wasn’t a major interest. Within my own family, I told my sons about the legendary ancestor who fought in the war as a boy, was stranded in Virginia at war’s end, and walked his way home to Mississippi. My father had told me that story, including how the family had never owned slaves and had always been shopkeepers.

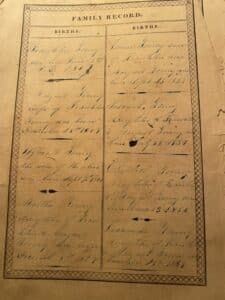

A page from the family Bible

Many decades later, I became interested in my family’s history, helped by relatives on both sides who were amateur genealogists. And I had the Young family Bible, with its pages of births, deaths, and marriages, and a couple of mysteries. I’d started rereading Civil War history, and I began to think about that family ancestor and what a novel he would make. I had no background in historical fiction, but I decided to give it a try. It would eventually become Brookhaven, a historical novel that is also a historical romance.

But first I needed to do a huge amount of research. I didn’t need to understand battle strategy; I needed to grasp how people lived, worked, fought, and survived, what they ate and how diets changed, what happened when they couldn’t get the basic necessities we take for granted. And I remembered my high school and college studies — go to the primary sources.

I turned to letters, speeches, diaries, census records, and newspaper reports. And I learned that virtually everything I’d been told about my legendary ancestor, the hero of my story, was not merely wrong; it was 180 degrees wrong.

It stopped my writing cold.

Next: 10 Great Sources for Learning and Teaching the Civil War (and how I decided to accept the truth about my ancestor but write the original story anyway).

Photo by Tatrattery, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

Oh, I really enjoyed this post.

And what a bold teacher (especially at that time?) to say, “Nah. We’re going straight to Das!” That totally made me smile. 🙂

Dave Malone says

That was a cruel cliffhanger at the end, Glynn, lol. I can’t wait to hear what transpired—how the story flipped 180 degrees .

Glynn Young says

Dave – see the followup story. https://www.tweetspeakpoetry.com/2025/03/06/10-great-resources-for-teaching-the-civil-war/

Dave Malone says

Thank you!

Michelle Ortega says

What an undertaking, but how rich a discovery!