About Karla Van Vliet

Karla Van Vliet is the new co-director at Anhinga Press. She is also a co-founder and editor of deLuge Journal, founder of the Van Vliet Gallery, and administrator of the New England Young Writers’ Conference at Bread Loaf, Middlebury College.

She is also the winner of the Bacopa Literary Review’s Visual Poetry Award, a finalist for the Edna St. Vincent Millay Poetry Prize, and a nominee for the Forward Prize and the Pushcart Prize (three times). Her poems have appeared in Acumen, Poet Lore, Green Mountains Review, Crannog Magazine and others. Her asemics have been published in WAAVe Global Gallery: Women Asemic Artists and Visual Poets 2021, Women Asemic Writing, UTSANGA.IT, Still Point Art Quarterly, Indelible Literary and Arts Journal, Harpy Hybrid Review, and Harbor Review.

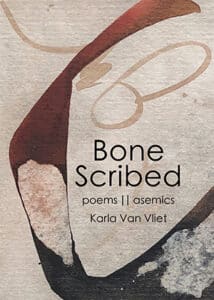

Van Vliet is the author of From the Book of Remembrance and The River From My Mouth, collections of poetry and paintings, published by Shanti Arts, a poem length chapbook, Fragments: From the Lost Book of the Bird Spirit, published by Folded Word, She Speaks in Tongues (Anhinga Press,) a collection of poems and asemic writings, and Fluency: A Collection of Asemic Writings (Shanti Arts.) Her latest books are Bone Scribed and Wildwood Devotions.

Listen In to Our Chat with Karla

Tweetspeak Poetry (TSP): Your work blurs the line between word and image. How does this play with or against linguistic “precision,” which is often something a poet seeks by trying to choose the just-right word or establish a just-right cadence?

Karla Van Vliet (KVV): Linguistic precision, very important to me… to follow the idea, thought, feeling, word, down to its root. Drawing nourishment from a word’s etymology, allows a deepening of the work, helps it land in the underlayers of one’s initial, or impulsive, word choice. And can, when done with intent, create multilayered meanings which adds to the work.

That said, there are times the words one wants or needs to express what is wanting to be expressed are not there for use. Either because they don’t exist in our language or are not yet fully formed in the writer… I think about asemic writing as filling that space between silence and word, that liminal space. The “precision” in the image aspect of my work comes from the use of asemic and image, abstract or not, to express that which has not yet come to me in word. I’m using image to gain that precision.

To push the meaning of cadence into the visual, if one can do that, cadence is found in spatial positioning, color, and tones.

TSP: Related, tell us if you admire any form poetry—or have worked with it as part of your artistic palette. Feel free to share any poem favorites.

KVV: I have, of course, put my hand to a few poetic forms; the sonnet for its turn, the villanelle for its repeating lines, Japanese haiku and tanka for their tightness of language and nature imagery. Forms can be helpful as they can force the writer to go beyond where they may otherwise go.

Still, I like the poem itself to dictate its rules. I call myself a lyrical poet. There is something in the leaping required by a lyrical poem that inspires me, opens the creative flow in me. This is one of my favorite feelings, both when I am reading a poem and when I am writing a poem. For me, the leaping is not only between images but through the feeling(s) that the images bring up in the reader. So that the understanding comes not so much through logic but through the felt experience of the poem. The lyrical poems I’m most attracted to incorporate nature imagery. This is something I use in my own work, too. I often say that I use the external landscape to describe my internal landscape.

TSP: Some of your work is described as “organic.” Can you tell us more about that? Does this concept spill into your life, beyond your art?

KVV: One aspect of “organic” that attracts me is that organic doesn’t need to be perfect. That a thing is as is it is naturally and that state holds a kind of beauty of its own.

It also resonates with the landscape that inspires my work; the river, rocks, the mountainous terrain I live in. Many of the abstract forms in my asemic paintings have the “organic” form of river stones.

Does the concept spill into my life, beyond my art? I’m not sure. The way it may spill into my life, beyond my art, is in my work to accept my own organic, non-perfect self, and in accepting others in their non-perfect selves. I think there is an emphasis in this country on being perfect, whatever that is, and it does a great disservice to us all.

TSP: You do a lot of asemic writing. It’s a form that is, paradoxically, wordless. Yet it seeks to make a mark. Can you explain how a poet might try asemic writing? What challenges might they face—and how can they meet those challenges?

KVV: For me asemic writing is the gesture of writing before defined meaning. I started writing asemics during the first time the one I will not name was voted in. I felt frozen and silenced in a trauma response. Asemic writing was my antidote to that. I thought of asemics as a way to keep my hand in practice so that when words returned, I would be ready.

Anyone who is interested in writing asemics need only to take up a writing instrument and move their hand in the gesture of writing. There is no right way. I think that is likely where the largest challenge might be, thinking there is a right way. There isn’t. Each person has their own gesture. Here are a few techniques to get your head out of the way…

Anyone who is interested in writing asemics need only to take up a writing instrument and move their hand in the gesture of writing. There is no right way. I think that is likely where the largest challenge might be, thinking there is a right way. There isn’t. Each person has their own gesture.

Here are a few techniques to get your head out of the way. Put on music, feel into the music and move your hand to it. Meditate for a time, in that state of being, move your hand across the paper letting the movements that rise up in you lead your hand. Prepare 20 pieces of paper, give yourself one minute to make gestures on each page. At the end of each minute switch to a new piece of paper.

Try using a pencil, a pen, a dip pen with ink. Use a paint brush, try using ink or watercolors.

As a writer I am comfortable with the horizontal line and with the vertical line. My writing follows those traditional customs. But one doesn’t need to follow those customs. Look up asemics online and see the great variety of asemics out there. Be inspired.

TSP: You have a collection of asemic writing that is “based on the voices of five women.” In what way does the collection interact with, or amplify, or honor, or… something else… the voices of these women?

KVV: For several years I drew the faces of women, hundreds and hundreds of faces. I drew them out of my head, that is, I wasn’t looking at faces and drawing them, I was just drawing them. I thought about my drawing of these faces as giving image to the women who have never been seen. Giving face to the anonymous. When I moved on to asemics I wondered if these women were rising up with voices. Voices that were not yet fully developed but developing through that liminal space asemics fill.

When Angina Press reached out to me to publish a collection, I realized that I had the opportunity to give voice to these five women. Each woman has her own voiced poem and five asemic images that reflect her as an individual. The project is an honoring of that process. From being seen to being heard. I think of this as an historical honoring of the anonymous as well as the personal journey I think many women must undergo bringing themselves into the world.

The title of the book, She Speaks Tongues, references this… the woman speaks tongues, as in languages, and also tongues, as in she speaks the holy language of her soul.

TSP: We’ve been thinking about the power of a single word—and considering a creative challenge around the concept. So we were especially intrigued with how your work often isolates words or phrases by bounding them with punctuation—specifically the forward slash. How did you begin this practice in your poetry? What effect do you hope it will have? (And are you familiar with the work of Juan Gelman, who also used slashes in what appears to be a similar way—but perhaps for different effect?)

KVV: I started using the forward slash as a way of noting time, a pause, a leap in image or idea, at the same time as holding the container of space. I frequently use them within the form of a prose poem. Often, I use them where I would have made a line break or stanza break if I wasn’t wanting the condensed shape of prose. Like musical notation they tell the reader how to read the line when I’m not using the traditional poetic ways of doing so.

I was not familiar with the work of Juan Gelman but am glad to have been introduced to his work. Reading his poems I think you are right that we use the slashes in a similar way.

TSP: DeLuge Journal. You’re the co-founder and editor. How did this effort begin? What do you hope others will receive from it?

KVV: I am co-founder and editor of deLuge Journal with Sue Scavo. We are both poets and dreamworkers (a way of working with dreams for personal growth) and we wanted to create a space to share quality creative work that speaks to, from, and about the inner experience. Our inaugural issue came out in 2015.

Our hope is that the work we present touches people, opens them to a space people often don’t allow themselves to enter.

TSP: And the Van Vliet Gallery! Ooo. We love the sound of that. Invite us into its space. (Do so with a small poem, with just a few words, or with some art.) How did this gallery come into being? What in your own life urged you forward in its creation?

KVV: This is how I say it on the VVG site…

“Adversity births innovation. In lieu of a brick-and-mortar gallery, I’m launching a virtual gallery to share the work of working artists I admire and to share my own work, as well.”

I launched VVG during Covid. I’d had several art shows cancelled and I was looking for a way to keep in relationship with the art world while in lockdown. I also wanted to open a space to share asmeics and present the work of asemic writers/artists from around the world.

I decided to try out a different business model from the usual gallery model. Any sales are made via the artist. This works well because the artists I show are worldwide and the shows are virtual. I take no percentage of those sales. I fund the project through sales of show catalogs. To date I’ve shared the work of twenty artists. Catalogs continue to be available for each show.

Last year I also published the anthology Glitchy Womyn, a collection of glitches (an art form using glitching as its foundation) by women around the world. Kristine Snodgrass and I edited the collection.

And I have just put out a series of blank books I call Catch Your Memories; each book uses the title as a writing prompt. For example: “What I Remember: Thoughts, Stories, and More of the Times We Spent Together” and “In Case I Didn’t Say: Thoughts, Stories, Lessons, and More For My Daughter After I’m Gone.” There are nine books in the series.

I love working in collaboration with the many artists I’ve shown; love curating the shows and creating the catalogs.

TSP: Speaking of being urged forward, if you could give wisdom to poets and artists about their own movement in the world of creative life, what would it be?

KVV: I urge those who want to create to listen to the “voice within” the intuitive voice, to trust it, follow it. Be inspired by what others are doing, sure, but let it be inspiration and not copying. Don’t even copy what you’ve done before; let what you’ve done before be only the starting point.

Allow your own creative journey to unfold. Go out on the so-called dangerous edge of your own knowing and jump into the void to see what is there. It’s brave and radical action. Be brave and radical.

Support in yourself the things that inspire you to create. Perhaps that is reading, always a good idea, or walking, or singing, or dancing, or working on the engine of your car, helping at a food shelf, talking to your neighbor. I like to gold pan in the stream near my home, listen to podcasts about history, survival stories, true crime, I garden. I look at the landscape around me, notice shapes, colors, textures. I pay attention to my dreams, my feelings, thoughts. Let all this be the ground your creative work draws from. Don’t let those voices of doubt stop you, do it anyway.

Try It: Asemics Prompt

Ever heard of asemics? Let’s try it out, using Karla Van Vliet’s techniques…

“Anyone who is interested in writing asemics need only to take up a writing instrument and move their hand in the gesture of writing. There is no right way. I think that is likely where the largest challenge might be, thinking there is a right way. There isn’t. Each person has their own gesture.

Here are a few techniques to get your head out of the way. Put on music, feel into the music and move your hand to it. Meditate for a time, in that state of being, move your hand across the paper letting the movements that rise up in you lead your hand. Prepare 20 pieces of paper, give yourself one minute to make gestures on each page. At the end of each minute switch to a new piece of paper.

Try using a pencil, a pen, a dip pen with ink. Use a paint brush, try using ink or watercolors.”

Photo by USGS, Creative Commons, via Unsplash.

- Top 10 Dip into Poetry - August 13, 2025

- Poetry Club Tea Date ✨ At the End - August 4, 2025

- Poetry Prompt: Gathering Flowers - June 16, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

I love the idea of using asemics when you feel in an inchoate state. I tried it over the weekend, and it was a very satisfying practice, Karla. Thank you for introducing me to this new form! 🙂 And thank you, too, for these stirring thoughts on art and poetry.

Laurie Klein says

Karla, what an elegant, lithe, fluidly striking expression you’ve shared as capstone to the interview! so invitational. For me, a summons to contagious gazing: watercolor wash, paper, ink—time’s fugitive palette giving a tip of the hat to copper’s patina.

A glimpse, perhaps, of a listening breathing, on paper . . .

Enchanting!

L.L. Barkat says

Laurie, your words here, a poem. I just love “time’s fugitive palette” and want to bring that with me, somehow, some way.

Laurie Klein says

L.L., thank you! Such a heartening start for my day, to picture that phrase traveling with you . . .