I started writing my historical novel in ignorance. But I learned.

Writing one historical novel does not make one an expert in the genre. I have written exactly one historical novel, Brookhaven, a romance set in the Civil War era and in 1915.

To write Brookhaven, I didn’t turn to how-to works by historical novelists, historians, or romance writers, or read articles on the subject on web sites. In fact, I never intended to write a historical novel at all. Because I had the time, I began to pursue a lifelong interest in the Civil War, with a side-interest in the role of my great-grandfather.

I also continued to read and do research, because writing this kind of story demands it. What did people wear? What did they eat? How would they send a letter when railroads and the mail service weren’t functioning? What were prisons like for captured soldiers? How does a society function when social order breaks down?

I learned some lessons along the way. Each was hard-learned and hard-earned. I stopped counting the times I had to go back and revise something, sometimes extending to almost everything I’d previously written.

If you’re thinking about writing a historical novel, I have seven suggestions for how to do it and not do it.

Tip #1: There is such a thing as too much historical research

You can research a topic, a person, an event, or an era to death. I know because that’s what I did. Brookhaven has an eight-page bibliography, and I didn’t even scratch the surface of what’s available on the Civil War. Civil War history is not a minor industry; it’s a major one. You must be selective about what you read and study.

Tip #2: Be open to what history can offer your story

Union graves at Shiloh

You think of military cemeteries, and you think of places like Arlington or (closer to my home) Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis. You see all those rows of white crosses, Stars of David, and other memorial stones. And then there’s a battlefield like Shiloh, where the Union dead were buried with markers, but the bodies of dead Confederate soldiers were dumped in unmarked mass graves. That became an element in Brookhaven.

Another interesting note: At the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia in 1864, Robert E. Lee was meeting next to a road with his commanders, when a Union detachment suddenly emerged from the woods not 50 yards away. Had those soldiers realized what they had almost stumbled upon, the Civil War might have been over much earlier. It’s a true story, and it found its way into Brookhaven.

Tip #3: Don’t let facts get in the way of your story

You don’t do something dumb, like rewrite the Battle of Gettysburg so the Confederacy wins. But I learned during the writing that my extended family believed something that simply wasn’t true. The reality was more prosaic, but I stuck with the original story because it was better.

Tip #4: Historians have biases

Historians write about past events, but they write within a particular cultural context. When I was in college, the “Lost Cause,” the belief that the Southern people had nobly fought to preserve American ideals and a way of life (never mind slavery), was losing its grip. The 1939 movie Gone With the Wind might have been the high-water mark of the Lost Cause belief. Today, the bias has flip-flopped. I started reading a biography of Robert E. Lee, and right in the introduction, the highly esteemed author wrote, “Of course, Lee was a traitor.” He had to write that in today’s cultural context (“You mean you wrote a whole book about a traitor?”). The biases extend to far more than leaders. What I did was to read old and new books, collections of letters and memoirs, and contemporary accounts to get some balance.

Tip #5: Consider family stories and legends as suspect until you find proof

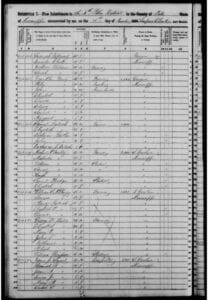

A page from the 1850 census showing the family

My novel started its life because of a family legend about my great-grandfather. Coming from a family of non-slave-owning shopkeepers, he’d been too young to enlist, so he became a messenger boy. At the end of the war, he’d had to walk home from Virginia or North Carolina to southern Mississippi. When he arrived, he discovered the family was gone, having fled to Texas. So, he continued his journey until he found them.

Virtually everything in that family legend turned out to be wrong. And I mean everything. The legend began to unravel when I looked closely at census records. Most especially difficult: I discovered that every census from 1830 to 1890 classified the family as “farmers” (who owned slaves) rather than a family of non-slave-owning shopkeepers. And the story continued to unravel.

Tip #6: Online genealogy sites can be more helpful than you realize

Sites like Ancestry.com and Family Search can provide a wealth of information about significant dates, lines of ancestors and descendants, and locations of births, marriages, and deaths. The web site contributors—the people who add information—are another great source. One of them even provided me with an alternative legend about my great-grandfather, the one that rang true and had some facts to back it up.

Of course, these sites can also provide surprises. There was a discussion thread in one in which a family member was complaining about how the Young family Bible had ended up with my great-grandfather’s youngest son, instead of the oldest, and “even now it’s in the hands of a great-grandson who lives in St. Louis.” Nothing to see here; move along, move along.

Tip #7: The family Bible can be a great source of facts—and mystery

The family Bible after preservation

Yes, I confess, there is a great-grandson in St. Lous who has the family Bible in his possession. He received it in poor-to-awful condition, wrapped in a paper sack and held together with twine older than he was. He did have the Bible rebound and preserved; the cost to restore it would have been prohibitive. But it contained family records stretching back to 1801, all written in the hand of my great-grandfather: eight pages of marriages, births, and deaths.

It also contained one mystery: the death of a Jarvis Seale was recorded. No birth or burial place; just the date of his death. My father had theorized it might be a distant cousin. My research for Brookhaven led me to the truth, and the key was the date of his death—April 6, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Shiloh. According to Family Search, he was married to a sister of my great-grandfather.

The online records say Jarvis Seale is buried in a cemetery in north Texas, and a tombstone certainly suggests that. As it turns out, the cemetery is in the same town where his oldest daughter lived and was buried; it is simply a memorial stone, so that he might be remembered. Jarvis had been buried in an unmarked mass grave in Shiloh. My great-grandfather had enough regard for him to include him in the Bible.

And I included Jarvis Seale, or his memory, in Brookhaven.

By the way, to mollify the complaining family member, I sent her photographs of the pages of Bible’s family records. I was a hero.

Photo by Fresh Waffles, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

I love this, Glynn.

Do you really think a writer can research too much? I felt that your book was so authentic, and it seems to me that maybe your deep immersion in the research helped that happen.

Brookhaven taught me so much about the American Civil War. I wish this is how I’d been taught the subject instead of the lackluster way I learned about it in school long ago! 🙂

And I loved the story. It made me think a lot. People just don’t know what they are saying when they suggest maybe America should step into another Civil War. Just, no. Read Brookhaven and think again. 🙂

Glynn says

I had to become selective; there’s so much that’s been written and researched on the Civil War that it can be overwhelming. I kept a writing diary for “Brookhaven,” starting in June of 2022. But the research began about 2016. And you can get mesmerized; the Civil War has so many incredible stories that you want to include.

One of those stories: I discovered during the research that my great-grandmother was descended from John Alden and Priscilla Mullins of “The Courtship of Miles Standish” fame. The temptation was huge to work that in somehow, given the Longfellow theme throughout the book. I decided not to; it would have been a side-story that would detract from the overall story.

The major impetus for the writing was the preservation of the family Bible, starting in the early spring of 2022. The expert who did it found (buried somewhere in the Old Testament) a lock of hair. Because the Bible had been in my great-grandfather’s possession for 50 years, and that all the family records were in his hand, I knew that lock had to belong to my great-grandmother. She died in 1888 at the age of 42, and he never remarried (he lived until 1920). I told myself that was a love story – and all that reading and research began to focus on how to tell it.

Sandra Fox Murphy says

Glynn, I loved this essay. So much great advice. I love writing historical fiction; however, my primary characters are mostly fictional, so I have more leeway. My first novel was “inspired by” a true family story (in the 1600s of Rhode Island). Much of it is truth based on facts and records, but I embellished and I always like to add a bit of mystical. Because it was my first novel, I always feel it could be better written, but I found the story to be fascinating. I did make good use of Ancestry.com in my research, in addition to other sources. My fifth book (the end of a trilogy) was set squarely in the Civil War–so much research!! The main characters were fictional, but the reality of place and time was important to me. Such a great way to learn history and to share history. I can’t wait to read your novel, Brookhaven, and I sent a copy to my sister who is reading it now. Glad to hear the story travels into Texas–I didn’t come from here, but after all the years, Texas has my heart.

Glynn says

We get some leeway with historical fiction, particularly with the characters. I turned one of my characters into something of a composite; virtually everything he does happened to someone during the period. And you’re right – it is a great way to learn history. I thought I knew a lot about the Civil War, but I didn’t.

Jody Collins says

Glynn, I enjoyed reading “Brookhaven” greatly–there was a lot of family to keep straight but the love story came through beautifully. What a labor of love–thank you for telling this story.

Glynn says

Jody, thank you! I’m so glad you enjoyed it (and you see why my wife told me to include a character list, which is toward the end.)

Sandra Heska King says

Oh my goodness. I love this piece so much I’m going to print it out. I tend to get bogged down in rabbit trails, but maybe that’s not so awful. Years ago I started what could maybe be a book if I live long enough based on a family story of my grandmother who fled through flames on a train to escape a Michigan fire. I got caught up in research. And then decided what I had written was pretty much junk. Maybe I’ll pull it out again one day.

Good, good stuff here. As always.