About Megan Merchant

Megan Merchant lives in the tall pines of Prescott, Arizona where she spends her days exploring, drinking too much coffee and avoiding the laundry.

She holds an MFA degree from UNLV and was the winner of the 2015 Lyrebird Prize, 2017 Beullah Rose Poetry Prize, the 2016-2017 Cog Literary Award, the Las Vegas Poets Prize, second place in the Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry, the Inaugural Michelle Boisseau Prize, and most recently The New American Book Prize. She is a multi-year Pushcart Prize nominee.

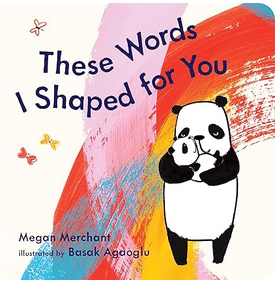

Megan has published five poetry collections: Hortensia, in Winter (2024) Gravel Ghosts (2016), The Dark’s Humming (2017), Grief Flowers (2018), and Before the Fevered Snow (2020); four poetry chapbooks; and a children’s book, These Words I Shaped for You. She is also the editor of the poetry journal Pirene’s Fountain and the owner of Shiversong, an editing, manuscript consultation, and mentoring business. She lives with her family in Arizona.

Listen In on our Conversation with Megan

Tweetspeak Poetry (TSP): You live in Arizona, where you spend your days exploring. Can you say a little more about what you explore? How do these explorations impact your writing life, if at all?

Megan Merchant (MM): When my youngest son was about four, he lost his ability to speak (he is on the spectrum and has epilepsy). We had recently moved from Las Vegas to Northern Arizona and, for the first time, had a small amount of acreage to explore. One of the only things that helped my son navigate the tantrums and frustrations of not being able to ask for what he needed was to wander outside, pick up stones and feathers, splash in our seasonal creek, watch the ravens flick from the pine tops. It was lifesaving, for both of us, this wandering, and a lot of the imagery in my earlier work came from the hours spent just being in nature with him. Eventually we were able to bring the words back, and we do less wandering now, but, for a few years, it was a crucial part of our existence.

TSP: Not only a writer but a translator, too? Wow! How did you get into translating? Do you think it has made you a better—or different—poet than you’d be otherwise? (Feel free to share a few snippets of a translation.)

From “Winter” (Luis Andres Figueroa)

Yes,

where a man’s space once was

that white of another world

has selfishly hidden the name of things,

sidewalks, birds, a bridge,

windows that turn off their light

in the coming of this violent season.

TSP: We admit: we didn’t know there was a university in Las Vegas! Did attending the University of Nevada in Las Vegas contribute anything unexpected to your life as a poet?

MM: I attended UNLV for undergrad as well—I was a Division One scholarship swimmer plucked from the Midwest. It is where I was able to sneak into my first creative writing course and fell instantly in love with poetry. I had no idea what was ahead when I applied for my MFA. Despite my parents’ protestations, I absolutely loved shifting my entire focus to poetry and creating. I learned how to be poet in the full sense of the word—how to be present with the world, develop an awareness for the ways in which I am able to (or not able to) move through it, how to look at language as more than just my personal history with it—understand the political, cultural, and social aspects to word and image choice. I spent significant time abroad working on a book of translation. I learned how to think critically about the work and was given space and time to develop my voice with support from a wonderful group of writers and teachers. Speaking of which, I have the opportunity to read with one of my former professors, Claudia Keelan, in Las Vegas on Nov. 15th—something that my twenty-two-year-old self would have never believed. I also had a lot of fun during my time at UNLV… and will leave it off there.

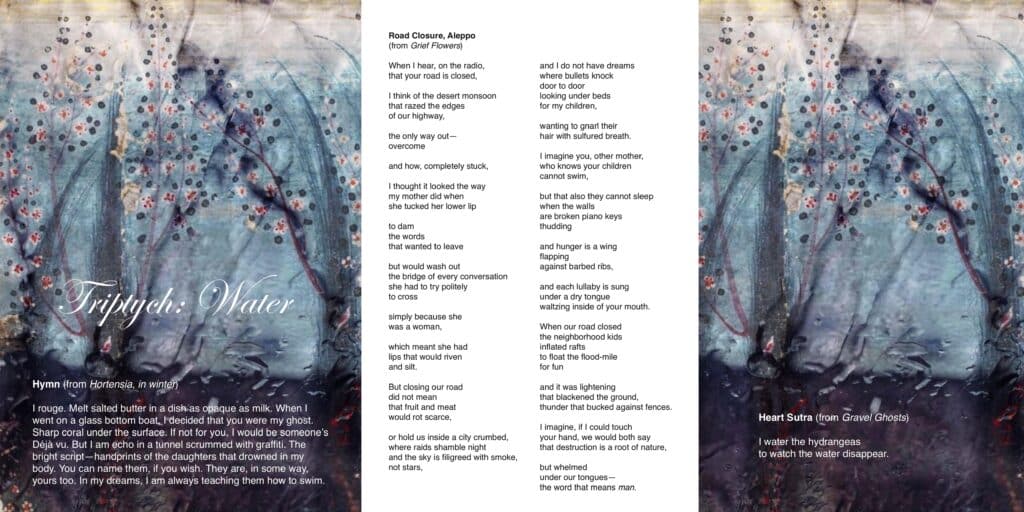

TSP: Here’s a small creative challenge: can you juxtapose three short poems, taken from three different published collections of yours, that maybe tell a new story here through their juxtaposition? Sure, you can give the triptych a name. ☺

MM: See below…

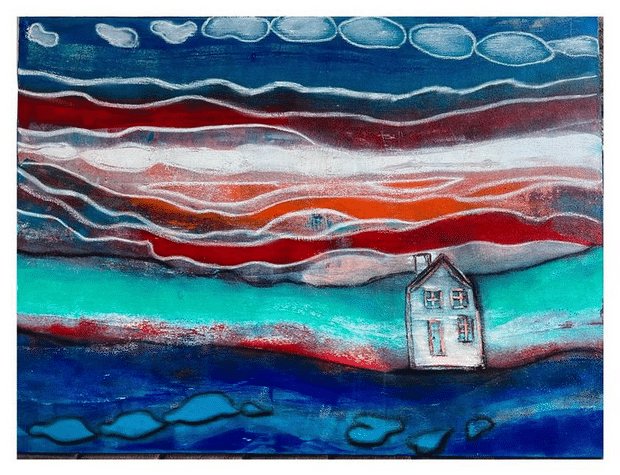

TSP: Speaking of triptychs, you are also an artist. We love your art! Here’s a piece, for example, that you said you realized needed to be painted after it wasn’t working out as a poem. How do you know when a creative idea needs to be a poem versus a painting? Do you ever take an idea and make it both?

(in the lost house, 2024)

MM: It’s funny, there are many times that I feel the creative impulse and sit down to write only to quickly figure out that I should, instead, be painting. Or vice versa. The creative process for me is very embodied—I feel it first, sometimes as a stirring or heaviness in my chest, and I have learned, over time, how to honor that without too much force of will or control. It’s usually a “sit down and find out” kind of situation. And sometimes I find out that what I am feeling can be translated into language, other times that image takes a more physical form and involves scissors and glue. I do really love ekphrastic writing, but only in response to other’s work. I haven’t yet figured out to access both avenues in my own sphere—the act of creating seems to want to live in separate boxes, but I’m hopeful that someday the two disciplines will have a more connected relationship.

TSP: Tell us about your children’s book, These Words I Shaped for You. How did it happen? What do you love about it?

TSP: Any advice for creatives who maybe feel a little doubtful about working cross-genre and cross-media? Is it harder to build audience when you do so? Should that matter? Advise us as if our souls depended on it. 🙂

MM: Life is short and weird—DO IT. The people who need to find your work because it speaks to what they are going through, or what they need to hear / feel / learn will find you. And at the end of the day, it’s not about displaying something for an audience, but connecting with them. It’s also about creating something rather than just consuming and honoring whatever it is that you have inside of you that needs a container. The container isn’t as important as what it contains. The most inspiring art is authentic art, and that takes vulnerability to create. I often urge the poets that I work with to get weird with it, share their oddities and quirks—what makes them unique and interesting. When that space is accessed and shared, it allows for that connection to grow—which, in my experience, has been the most profound and rewarding element of creating. It is also a way to connect with myself—to grow in understanding about the person that I have become, am becoming, and want to become. When I first embarked upon visual arts, I had no idea what I was doing and made beautiful “messterpieces”, but it offered me a whole new way of navigating the world. It’s more than okay to create a lot of sloppy copies and be terrible at something new. That kind of space offers a lot of freedom and playfulness. So, yeah—DO IT!!!!!

All art by Megan Merchant. Triptych image created by T.S. Poetry, using Megan’s art and poems she chose for the triptych.

Read our review of Megan Merchant’s new collection Hortensia, in Winter

- Braving the Poem: Interview with Catherine Abbey Hodges - March 24, 2025

- National Poetry Month Is Here + Prompt! - March 14, 2025

- Making & Unmaking Meaning: Interview with Wendy Wisner - March 3, 2025

Leave a Reply