Meet Poet Jules Jacob!

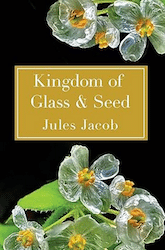

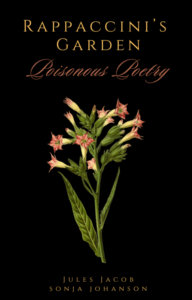

Jules Jacob is the author of Kingdom of Glass & Seed, The Glass Sponge, a semi-finalist in The New Women’s Voices Series (Finishing Line Press), and co-author with Sonja Johanson of Rappaccini’s Garden. Her poems are featured in Lily Poetry Review, Plume Poetry, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Rust + Moth, and elsewhere. Jules is the recipient of a fellowship from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts at Le Moulin à Nef, Auvillar, France. She is an Emeritus Master Gardener and has studied Horticultural Therapy.

Tweetspeak Poetry (TSP): Jules, you have had two collections come out within a year. One as a co-author and one solo. How has it been to try to promote two collections at once? And, we’d love to hear some specifics regarding your happiest promotional efforts.

Jules Jacob (JJ): Promoting two collections—Rappaccini’s Garden was officially released August 12, 2024, and Kingdom of Glass & Seed (Lily Poetry Review Books) October 9, 2023—has been exhilarating and at times tricky as far as dividing my attention between two books. It’s required good organizational skills, patience, and assistance from my publishers and co-author. Peer support and social media networking and opportunities such as this interview have helped with publicizing two collections, which coincidentally were accepted within one month of each other. Thank you!

I was delighted when Martha McCullough, Lily Poetry Review Books Designer, accepted my idea of using a photograph of a skeleton flower (Diphylleia grayi) for the cover of Kingdom of Glass & Seed. Sonja Johanson and I were hoping for a few botanical illustrations in Rappaccini’s Garden and were thrilled when Courtney Jameson told us White Stag Publishing would illustrate every poem.

TSP: Two of your poetry collections have glass in the title. Tell us more about that. Do you have a special affinity for glass? (Or did it find its way to you? ☺ )

JJ: I learned about glass sponges—creatures made from silica, thriving in the sea for thousands of years, and thought to be extinct until 1970—while writing my first chapbook. When I was searching for cold tolerant plants, I came upon the skeleton flower, which turns clear as glass when it rains.

When I was a kid I found several antique bottles on my grandparents land in New Hampshire. I thought they were fascinating. They reminded me of sand and the sea, plus glass bottles were inexpensive to collect. I learned to differentiate between hand-blown bottles and those with side seams molded in factories. I looked for bottles that turned blue or purple over time when exposed to sunlight due to the addition of manganese dioxide from the years 1885 to 1914.

I love the aesthetics of conservatories, old greenhouses, and pre-WWI Christmas ornaments. I learned to cut glass, solder lead, and create glass art while working part-time in a stained-glass shop in my mid-forties. I find the transformative and potentially harmful properties of glass, and juxtaposition of fragility and beauty intriguing. I’d say I have an affinity for glass—or an affliction. It’s hard to ignore a broken window with a hole the size of a baseball in an abandoned blacksmith shop.

TSP: You’ve won a lot of contests with your poetry. How did you get started doing contests? Why should (or shouldn’t) a poet spend time on entering them?

JJ: I entered poems and ultra-short stories in contests early on when there were few entrance fees. My first chap collection, The Glass Sponge, was awarded publication in a contest in 2012. I’ve entered contests in the last six years; however Kingdom of Glass & Seed and Rappaccini’s Garden were both accepted for publication during open reading periods. In 2022, I invested fee money in two full-length manuscript consultations. I don’t recommend spending hundreds of dollars on contests. Open reading periods and low fee or no fee contests are worthwhile for poets who are willing to spend time scouting journals and presses they believe would best represent their work.

TSP: You were born and raised in Colorado. Has that influenced your poetry in ways you could point us to? (And, did you start writing poetry while you were in Colorado? Or did it enter your life later on?)

JJ: Colorado was foremost in influencing nature and place-based poetry. My family explored, hiked, and camped in the Rockies. We traveled to national parks across the country and spent summers in New Hampshire. My father, a former high school botany and chemistry teacher, still manages the family’s blueberry farm. I was twenty-eight when my first poem, ironically about my grandfather’s sawmill in New Hampshire, was published in the Colorado Gallery of the Arts.

TSP: We’re curious how you met your co-author Sonja Johanson. Also, what led you to work together on Rappaccini’s Garden?

JJ: Sonja and I were in the same online group of poets, but it wasn’t until I attended an International Master Gardener Conference in 2015 and learned the Master Gardener Coordinator for Massachusetts was named Sonja Johanson, that I realized the woman at the convention center was probably the poet, Sonja Johanson. I messaged poet Sonja and asked if she was at the international conference. She said yes, and promptly looked up my work, discovering that I’d written poisonous plant poems. Sonja also wrote poisonous plant poems and in 2016, she suggested we collaborate on a chapbook of poisonous plant poems.

TSP: Oh! You studied Horticultural Therapy and are an Emeritus Master Gardener. Tell us about these aspects of your background. And, did you ever foresee they’d inform your poetry?

JJ: I became a Master Gardener in 2005 to spread knowledge and information about gardening through community outreach programs as a volunteer for the University of Missouri Extension. I figured the experience would inform my poetry from a naturalist perspective but couldn’t fathom how deep and diverse the people-plant connection would be in a poor county in Southwest Missouri. My observations led me to enter a two-year Horticultural Therapy Certification program through the Horticultural Therapy Institute in Denver, accredited through Colorado State University. This experience deepened my understanding of the creative/destructive duality inherent in mankind and nature.

TSP: If you had it to do over again, would you still become a poet? Whether yes or no, what has it meant to you to be part of this world?

JJ: I don’t know if I became a poet, was poetically inclined and/or was just exposed to poetry as a child. My mother, an English teacher, told me my great-grandfather recited W.B. Yeats to her when she was young. I read avidly as a kid and had access to the library and old books, including poetry. I hope I’d follow the same path given the same set of childhood circumstances. As I’ve become more immersed in the poetry community and made lasting friendships, I can’t conceive of a different life.

Photo by Hannah Murrell, Creative Commons, via Unsplash.

Come to the Garden Party

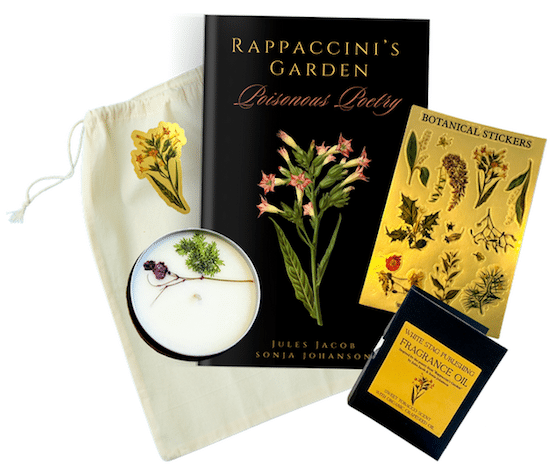

You can hear Jules and Sonja read from Rappaccini’s Garden on Tuesday, October 8, 2024. Sign up for the event, here. There will also be a chance to win a copy of their book + fun things that their publisher has paired with it for the “full set.”

- Top 10 Dip into Poetry - August 13, 2025

- Poetry Club Tea Date ✨ At the End - August 4, 2025

- Poetry Prompt: Gathering Flowers - June 16, 2025

Leave a Reply