We certainly didn’t think of “Catholic” poetry or fiction as something distinct. Poetry was poetry, and fiction was fiction. We did learn about the importance of Catholic faith when we studied T.S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and John Henry Cardinal Newman, or Reformation writers, or the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. But no one talked about a distinct Catholic literature, even if it might have existed. If anyone had asked me to name a Catholic writer, I would have said G.K. Chesterton, Flannery O’Connor, or Giovanni Guareschi, author of the Don Camillo stories (which I read in high school and loved). And that would have exhausted my knowledge.

But that was then, and this is now. Much has changed in the Catholic church, not the least being the changes of the Second Vatican Council and the abuse scandals, which not only engulfed the church but led to diocesan bankruptcies, school and church closings, and a staggering number of lawsuits and investigations. A church that was so much a part of my childhood and teen years was clearly diminished; many said it would never recover.

And yet.

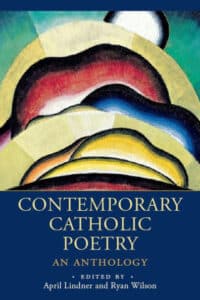

For at least the last 20 to 30 years, something has been happening in what we now call Catholic literature. It might be a mini-renaissance of a kind, and it might be a full-blown renewal. But something is clearly astir. Signs abound, like the founding of Paraclete Press in 1992 and Wiseblood Books in 2013, and the new Master of Fine Arts program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston. Catholic poets like Dana Gioia, James Matthew Wilson, and Angela Alaimo O’Donnell have gained widespread recognition for their work. Writers (and poets) like Joshua Hren and Sally Thomas have attracted attention far beyond Catholic media and literary critics.

The collection focuses on poets born after 1950, with the youngest being editor Wilson (1982) himself (Lindner is also included, with six poems). The format for each of the 23 poets is the same — a short biographical note, followed by five or six poems. Gioia, O’Donnell, and Wilson are included, as are Julia Alvarez (whose novel How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents I read more than 30 years ago), Maryann Corbett, Marie Howe, and Franz Wright, among others. The poets are not necessarily “practicing” Catholics; an editorial note explains the definition used was “baptized in the Roman Catholic faith.” But the point is well taken; being born and raised in any church will leave a lasting influence.

It’s an anthology that’s difficult not to enjoy. The Catholic influence is there, but these poets are also among the best writing today (a few of those included are deceased).

One poet whose selections I especially enjoyed and had not read before was Daniel Tobin, who’s won a considerable number of prizes and fellowships for his work and been published in such journals as Paris Review, The Hudson Review, Best American Poetry, The Southern Review, and many others. The following poem mirrors Shakespeare in a very deliberate way.

“Where the Late Sweet Birds” by Daniel Tobin

Daniel Tobin

As though I’d summoned it with the word behold,

A starling flew from maple leaves that hang

Above my patio, green shade, and summer cold

As fall. A plane flared overhead. Nothing sang.

Jackhammers clanged the heart out of the day

While the sun arced imperceptibly west.

The bird scavenged before it flew away,

Scraps among poly-noses and the rest

Of what spring had rained down: lust’s golden fire

To fill the earth with passing. It’s no lie,

The wind with its sleight from aspire to expire,

And the wish I wished as the bird streaked by

Longing, in its dumb way, to make the thing strong—

The nest toward which it flew that will not last long.

A footnote with this poem points out that this poem plays bouts-rimés with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, using the same rhyme-words in the same order.

The editors bring a wealth of experience to the collection. Lindner has written three young adult novels and two poetry collections. She’s also served as co-editor of Contemporary American Poetry. In addition to writing literary criticism, she teaches writing at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia. Wilson has published one poetry collection; another will be published this year by LSU Press. He’s received several poetry prizes and recognitions, and his work has been published in such journals and anthologies as Best American Poetry, Christian Poetry in America Since 1940, Birmingham Poetry Review, The New Criterion, The Hopkins Review, and many others. He teaches at Catholic University of America and the MFA program at the University of St. Thomas.

Wilson has also written a gem of an introduction to Contemporary Catholic Poetry.

It’s a stellar anthology, with the poems and poets chosen with care and informed understanding. The poems of each included poet easily serve as an introduction to his or her work. Reading a volume like this underscores the influence of the Catholic faith on their poetry as well as suggesting a cultural renewal is well underway.

Photo by Lukas Schlagenhauf, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Leave a Reply