Poet Juana Inés de la Cruz knew love, faith, and controversy

Reading about the life of Sor (Sister) Juana Inés de la Cruz (ca. 1650-1695) brings to mind the old, old adage of “the irresistible force meets the immoveable object.” The immoveable object was the culture of 17th century Baroque society of New Spain (Mexico). The irresistible force was a young woman’s love of learning and her writing. Something would eventually have to give, and eventually, something did.

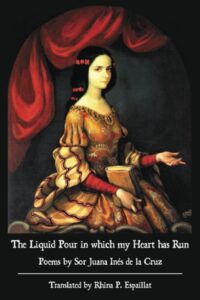

A new translation of 23 of her poems, The Liquid Pour in which my Heart has Run, has been published by Rhina Espaillat, herself a poet. It’s a small but representative sample of Juana Inés’s poetry

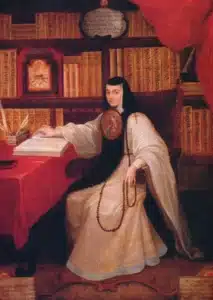

Juana Inés de la Cruz

Born out of wedlock to a Spanish officer and a New Spain Creole, Juana grew up on her maternal grandfather’s hacienda, with full access to and use of his library. She became a sponge for learning. When she was 16, she was sent from the hacienda to relatives in Mexico City. She caught the eye of the viceroy and vicereine of New Spain, and their patronage led to her growing recognition as a poet, philosopher, and scholar. Preferring a scholarly life, she declined to marry and instead joined the Discalced Carmelites. She was about 17 years old.

It wasn’t Juana’s poetry but her criticism that got her into trouble with the church. As poet Sally Read explains in her excellent introduction, Juana wrote a criticism of a local priest’s sermon. The bishop of Puebla published it, without her consent. The upshot of the controversy was that Juana’s penance was to forgo writing and literary study altogether. She would die in 1695 from the plague that afflicted her while caring for other nuns suffering from it.

Translator Espaillat has selected an array of Juana’s themes — love, unrequited love, truth, pain, and the general experiences of life. The English translations are placed adjacent to the original Spanish versions. Juana’s poems are neither plaintive nor shrill, even when she writes of unfulfilled love. She exhibits the mind of the scholar and philosopher she was. But she is also passionate. And you realize what a force she must have been to reckon with in both the church and the viceroy’s court.

In Pain as From a Mortal Wound

lamenting how Love did me injury,

and wished approaching death would set me free

if agony were only amplified.

My soul, with pain alone preoccupied,

tallied its sum of griefs incessantly,

concluding that a single life must be

a thousand deaths endured, and more beside.

And now, after another blow, my heart,

going down in defeat, uttered a sigh,

contemplating the end. But with a start

I turned toward reason—though I don’t know why;

recalled—and told myself—this wiser part:

Who has been luckier in love than I?

Rhina Espaillat

Espaillat is the author of 11 books of poetry, short stories, and essays, and three poetry chapbooks. She’s received numerous awards for her poetry and translations, including the T.S. Eliot Prize, the Richard Wilbur Award, the Howard Nemerov Prize, the May Sarton Award, the Robert Frost Award, and others. Her poetry translations have included works by Richard Wilbur and Robert Frost, translated into Spanish. She is also active with the Powow River Poets, a literary group she founded in 1992.

Juana Inés de la Cruz died still doing her penance. But the bishop and the priest involved in the controversy are long forgotten, while she became known as the “Phoenix of the Americas,” one of the finest poets and writers of the Spanish Golden Age. With The Liquid Pour in which my Heart has Run, Rhina Espaillat has created a wonderful introduction to this remarkable poet.

Related:

Take Your Poet to Work Day: Juana Inés de la Cruz

Poets and Poems: Rhina Espaillat and After All

Photo by John-Morgan, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

Leave a Reply