Herman Melville turned from fiction to writing poetry.

Writing and research can take you down some unexpected but rewarding alleyways.

For the last two-plus years, I’ve been involved in a writing project about the Civil War. Along the way, I learned that stories passed down as family lore turned out to be, well, stories of the fictional if well-meaning kind. History can teach you a lot about where you came from. Or not.

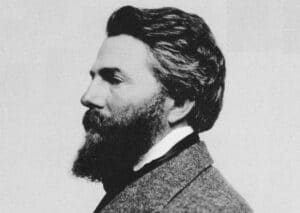

Part of my research has been reading novels and poetry about and from the Civil War. As I started, two poets who immediately came to mind were Walt Whitman (“O Captain! My Captain!”) and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (“Christmas Bells” and “A Nameless Grave,” not to mention his poems on slavery). One poet I did not consider, simply because I was ignorant of his poems, was Herman Melville (1819-1891).

In this case, my ignorance was rather profound. Only when I saw a listing in a promotional advertising flyer for Melville: Complete Poems from the Library of America did I discover that Melville was not only a novelist but also a poet.

Melville gained success early with his travel adventures Typee and Omoo in 1847. His next three novels weren’t successful. In 1851, he published Moby Dick, the novel for which he would become famous, primarily after his death. The work “didn’t find an audience,” which is the publisher’s way of saying “we really liked it but it didn’t sell.” His 1852 novel Pierre wasn’t well received by critics. He continued to write short stories and novellas like Bartleby the Scrivener. His final novel, The Confidence-Man, was published in 1857. In 1863, his literary career seemingly at an end, he obtained the post of customs inspector. Even writers have to eat and feed their families.

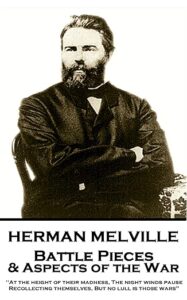

Melville didn’t stop all of his literary efforts, however. He turned to poetry. And the first poetry collection he published was Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866), some 72 poems about the Civil War.

Herman Melville

What we don’t know about these poems would make its own novella. As Stanton Garner, the author of The Civil War World of Herman Melville (1993) wrote, virtually no references exist for how Melville wrote these poems – no mentions in letters, no journal or diary entries, no notes, and no military experience. Melville did not participate or even try to enlist in the war, so the poems themselves contain no overt or implicit biographical information. It’s almost as if the poems arose on their own.

And yet, reading them, one can see the well of sometimes raw emotion from which they came. The Civil War deeply affected the lives of all Americans, no matter where they lived or their position in society. More Americans died in this war than other. Tens of thousands of veterans missing an arm or a leg continued to remind everyone of the war, long after it was over. For generations, the war became a fixture in American thought, either as a victory over slavery or the Lost Cause. My own beloved Louisiana grandmother always referred to it as “the war of northern aggression.”

So, the emotion of Melville’s poems is no surprise. The subjects of the poems show how closely he followed newspaper and other official accounts. Not even Whitman kept a poetic record of battle after battle and an account of many of the generals like Melville did. He wrote of Northern victories and defeats. He recognized William Tecumseh’s Sherman Atlanta campaign and march through Georgia. He felt the fall of Richmond in 1865.

And Melville mourned the soldiers who died. Known as an intensely private man, he bared his heart in these Civil War poems, and not only for the Union fallen.

On the Slain at Chickamauga

Who through long wars arrive unscarred

At peace. To such the wreath be given,

If they unfalteringly have striven —

In honor, as in limb, unmarred.

Let cheerful praise be rife,

And let them live their years at ease,

Musing on brothers who victorious died —

Loved mates whose memory shall ever please.

And yet mischance is honorable too —

Seeming defeat in conflict justified

Whose end to closing eyes is hid from view.

The will, that never can relent —

The aim, survivor of the bafflement,

Make this memorial due.

Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War is more than a poetic account of battles and generals. Melville, sitting in his home or customs office in New York City, grasped that the war was changing everything. His poems have some sense of nostalgia, as if he knew that nothing would ever be the same. He honors the dead, he recognizes the heroes, and he states his hope for the future.

Melville would publish five more collections of poetry, including Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land which runs for almost 500 pages. He would stop writing altogether in 1876, retire from his job in 1885, and die of a heart ailment in 1891.

He was never the “forgotten writer.” A few critics knew Moby Dick was a masterpiece. It was the posthumous publication of Billy Budd, an unfinished novella, in 1924 that made a major impact on Melville’s literary reputation. He would be fully recognized for the achievement that’s Moby Dick.

But there’s the image of the writer sitting at his desk, trying to make sense of a war that turned America upside down, carefully describing major battles and events as if he had to record them. Or else lose them.

Related:

J.D. McClatchy Tells the Story of the Civil War – in Poetry.

Photo by Holly Norval, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

The things we miss! I had no idea Melville turned to poetry. Let alone Civil War poetry.

Thanks for bringing this upwards, Glynn. History is important to keep close. And, literature helps us keep its soul.

Glynn says

I, too, didn’t know about Melville and poetry. I stumbled into his Civil War poetry via Longfellow. The novels that made his reputation were largely unsuccessful when published; it wasn’t until 30 years after his death that they were “discovered.”