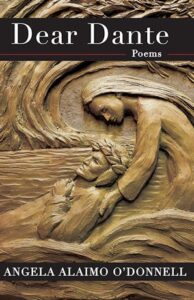

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell has a (poetic) conversation with Dante

If I were asked to name the greatest poets in human history, I would likely name five: Homer, Virgil, Dante Alighieri, Geoffrey Chaucer, and John Milton. There they are: a Greek, a Roman, a Florentine, and two Englishmen. Yes, the list reflects my Eurocentric perspective, but there it is.

Dante (1265-1321) serves as a pivot point between the classical world of Greece and Rome and the more recognizable modern world of Milton. Chaucer (ca. 1340s-1400) is chronologically close to Dante and is believed to have memorized at least parts of Dante’s The Divine Comedy by heart. While many of the people mentioned in The Divine Comedy are not well known today outside their own historical era, that doesn’t detract from the greatness of the poetical work.

Dante Alighieri

In the summer of 2021, to mark the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, poet Angela Alaimo O’Donnell decided to reread The Divine Comedy by one canto a day (100 cantos, she wrote, and about 100 days of summer, seemed an almost perfect match). She discovered that while she remained deeply impressed by “the beauty, power, and wisdom of Dante’s epic account of sin, purgation, and salvation,” she did take issue with some aspects of his worldview.

Fair enough. But having read the great work, I discovered that, Reformed Presbyterian that I am, I might be more comfortable with Dante’s medieval worldview than a contemporary one. But then, I also like G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) and J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973), two other somewhat medieval Catholics in outlook, if not chronologically.

O’Donnell did more than read the cantos. She responded to them, sometimes deeply so. Then then she did what you might expect a poet to do: she began a conversation with Dante, in the form of poems. The result is her latest poetry collection of 42 poems, Dear Dante, consisting of a prologue poem, two epilogue poems, and 39 poems in between, with 13 for each of the divisions of The Divine Comedy — Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

In responding to Dante, she’s almost paying homage, in both subject and form. The reader begins to imagine that O’Donnell is quietly following Dante and his guide Virgil as they traverse Hell and Purgatory, and then Dante alone in Paradise (as a non-believer, Virgil couldn’t enter Paradise, despite how much admiration and guidance Dante felt). Because she had read Dante before, she generally knows the way he’s following. But she discovers, like any rereading will provide, new insights, and not only about Dante.

Swimming with Dante

Have stepped in it a time or two, and more.

Have felt it burn in my soles. Left the shore

of sanity and love to wade its waters,

immerse myself in wrongs I could not right,

conjure violent wars I could not fight,

boil awhile in blood, my own and others’.

Anger is a pleasure. Anger is a cage

that holds the soul in bondage to its whim.

Once you’ve wandered in, all the brim-

stone in Hell cannot save you. No centaur

will rescue you (like lucky Dante). Forever

caught between desire and desire, you swim

until the madness leave you again.

The poems are personal, conversational, and accessible, whether O’Donnell is walking with Dante among the lovers or suicides, the envious or the avaricious, the blessed souls, or watching as Dante loses his muse Beatrice.

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell

O’Donnell’s ten other collections of poetry include Andalusian Hours, Still Pilgrim, Saint Sinatra & Other Poems, Moving House, Waking My Mother, Lovers’ Almanac, Waiting for Ecstasy, and Mine. Her poems have been published in numerous literary journals and magazines. She’s a professor at Fordham University in New York City, where she teaches English, creative writing, and American Catholic Studies. She was graduated from Penn State University and received her master’s and Ph.D. degrees in English Language & Literature from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The translation read by O’Donnell is by Allen Mandelbaum. My own favorite is the John Ciardi translation. Well-known writers have also undertaken translations over the years, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Gustave Dore, and Dorothy Sayers.

Dear Dante is a response and an ode of tribute. It’s also something of a guide, not to Dante on his journey, but for the contemporary reader who might decide to read the great work. What O’Donnell does is suggest how so much of The Divine Comedy still resonates and still applies. As she makes clear, Dante struggled with many of the issues of the human condition we struggle with today.

Related:

Poets and Poems: Angela Alaimo O’Donnell and Holy Land

Poets and Poems: Angela Alaimo O’Donnell and Still Pilgrim

Poets and Poems: Angela Alaimo O’Donnell and Andalusian Hours

Poets and Poems: Angela Alaimo O’Donnell and Love in the Time of Coronavirus

Photo by TANAKA Juuyoh, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Boris Dralyuk and “My Hollywood” - September 9, 2025

Leave a Reply