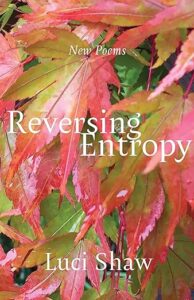

Luci Shaw strives to bring order and meaning from the chaos of life

You read the poetry collection Reversing Entropy by Luci Shaw, and you’re surprised by how consistent, and often confused, your responses are.

You know these poems had to have been written in a plainly finished, almost spare room, at a table in the center, as the early morning light streamed in. And yet you also know, from the evidence within the poems themselves, that they’ve been written indoors, outdoors, in the midst of wrenching grief and great joy, and sometimes even from the front seat of a moving car. Shaw uses the word “scribbled” a lot. How can these beautiful poems be merely “scribbled”?

If you’ve read any of Shaw’s previous poetry collections, you know what a practiced, precise eye she has for nature — the light reflected from a lake’s surface, the individual perfection of flowers like lilies of the valley, the leaves of a ginkgo tree. Description can be a kind of ordering and defining. Shaw goes beyond — far beyond — description, though, like finding meaning in the one fallen leaf that has managed to adhere to the car’s windshield courtesy of the rain.

These poems must have been worked over, every word carefully measured, every image defined and enlarged, every metaphor carefully chosen and weighed, discarded and replaced if deemed necessary. You do not expect Shaw’s words and ideas to have shown up like a gaggle of noisy tourists, snapping smartphone pictures of everything that can be photographed. But, she tells us, that’s what often happens.

How It Happens

like tourists with cameras primed for the views,

they show up to be introduced. Yesterday they

arrived late morning, bringing with them

bunches of exotic wildflowers and birds

with songs like bells ringing. For snacks, they

unpacked fragrant fruit to be nibbled

under the jacaranda trees. I inhaled their syllables’

soft breath, allowing them time to simmer into

some crisp internal identity, some fresh, surprising

sound or color. The words arrive visible,

like dandelion seeds that speak themselves into the air…

Then, surprise, a fresh phrase shows up,

tingling, excited to be invited, welcomed to

the party. I begin to sense the phrases thinking back

at me, thinking me in a sweet, internal colloquy—

interested in how our words sound

when spoken together into the bright air.

This is how my mind disputes amicably with

itself, one of the ways creation happens,

how freshness breaks in. How a new, crunchy

poem can begin, impatient, demanding to be

written down. And that is how a poem happens.

What we don’t see is the chaos in which these poems originated. And that is the idea of Reversing Entropy. The poet helps to bring order from the chaos of life. Life, and the universe, tend toward chaos and disorder, and creative activities like poetry, she writes, “are human efforts to halt and reverse this loss of meaning.”

Luci Shaw

That’s what Shaw is about in these poems — reversing the loss of meaning. It’s in her poems about nature and in the poems she writes about poetry itself. She writes of her faith and of “love in the time of plague.” The poems written in memory of her late younger brother John are aimed at bringing meaning out of loss, in itself a kind of chaos.

Shaw, a native of England, has lived in Canada, Australia, and the United States. Since 1988, she’s been writer-in-residence at Regents College in Vancouver, British Columbia. She has published 15 poetry collections and several nonfiction books, including three co-authored with Madeleine L’Engle. She has also edited three poetry anthologies and served as editor of Radix Magazine. She graduated with high honors from Wheaton College in Illinois.

Shaw is 96 this year. I don’t know whether she plans more collections after Reversing Entropy, but I do know that she will always see her work — what she’s called to do — as bringing order from disorder; taking the words, ideas, images, and metaphors that arrive as noisy tourists, and organizing them so that their meaning becomes clear.

Related:

Eating and Drinking Poems: Storytelling and Luci Shaw’s Eating the Whole Egg

Photo by Paul can de Velde, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Leave a Reply