Laurie Klein explores how our childhood is always with us

Begin with a house. Perhaps it’s the house you grew up in. Or the house you remember best as a child. I can remember lying awake at night, looking at how the hall light made a triangular shadow on my bedroom door, and forever associating that shadow with the murmur of my parents’ voices in the kitchen. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but hearing the murmur was always reassuring.

Memories float through that house, some vivid and some vague. The house is its own presence, but it also serves as a kind of table of contents or a framework surrounding what we really remember from our childhoods. And that’s usually the people — parents, siblings, friends, neighbors, and relatives. It’s odd that some of my sharpest memories of my maternal grandmother and my aunts, uncles and cousins are associated with my own house, not theirs. Perhaps it’s because our house was the gathering place for family celebrations and holiday dinners, and my relatives always stood out more clearly in a different environment from their own.

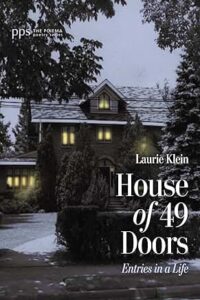

In House of 49 Doors: Poems, Laurie Klein starts and ends with a house, too — the Fowler house. It serves as the framework through which the memories of childhood and family are channeled. It’s the Fowler House that has 49 doors. You might, or night not, know what each door opens to.

The poems are “told” through one of two personas. Larkin is the child, owning and discovering the world around her. Eldergirl is the older, and presumably wiser, persona. Their poems weave back and forth from past to present, underscoring that the past is never really past and the present was once the unknown future. Both Larkin and Eldergirl are our hosts for a tour, which includes the premises, the hall, the first floor, the stairwell, the second floor, that tic, the roof, and even the laundry chute.

I didn’t grow up with a laundry chute; we didn’t have basements in New Orleans. Our oldest child, however, did have a laundry chute, and put everything imaginable down it. We learned that opening the chute door in the basement could almost be a lethal experience.

As Klein reminds us, childhood memories can erupt into our adult minds at the smallest prompting, or in the most unexpected ways. You might be walking along a shore, getting over the flu, seeing a snail on the sidewalk, or even swimming in a pool, and suddenly years disappear and you’re a child again.

While Swimming Laps, Eldergirl Remembers

Her Childhood Tree House

its yellowing gloves,

and in my freckled, believing

hands, those oblong leaves

became funnels for fireflies,

each tenderly rolled cone

painstakingly stitched

closed, with a twig. I remember,

now, during lightless times,

those teeming jewels no longer

afloat in autumn twilight. And,

like an exile, I keep feeling around for

the old contours. Shelter. Mostly,

the twinkling.

Some of the most moving poems are about “Uncle Dunkel.” We see him first through a child’s eyes; we’ll eventually see him through an adult’s understanding. Not every family has an Uncle Dunkel, but he’s instantly recognizable and familiar. He might be an uncle, a brother, or an older cousin, but he occupies, or comes to occupy, the position of family irregular, if not black sheep. Klein’s poems about him will make you smile in recognition and in memory.

Laurie Klein

Klein has been a songwriter, artist, actress, mime, clown, storyteller, audiobook narrator, teacher, director, writer, and editor. She wrote the classic praise song “I Love You, Lord” and received the Thomas Merton Prize for Poetry of the Sacred. Nominated for both poetry and prose for the Pushcart Prize, she previously published the poetry collection Where the Sky Belongs. She blogs at Laurie Klein Scribe and lives in the Pacific Northwest.

House of 49 Doors surprises, saddens, and evokes more than one smile. Klein is opening her memory and her heart here. Memories of childhood can often be funny and sometimes painful. But we cling to the living, and we cling to the loss, and we’re human for knowing both.

Related:

Poets and Poems: Laurie Klein and Where the Sky Opens

Photo by ulricaloeb, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- 10 Great Resources for Teaching the Civil War - March 6, 2025

- Relearning Civil War History to Write a Novel - March 4, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Marjorie Maddox and “Seeing Things” - February 27, 2025

bethany says

What a beautiful image you’ve shared about that trianglular shadow on your childhood door and its connection with your parents’ voices. Thanks for sharing this with us.

I’m currently reading Laurie’s collection and appreciate your take on it. She’s an incredible writer and artist. Love so much that firefly poem of hers. “Once upon a tree…” <3

Glynn says

Bethany, thanks for the comment. It really is a beautiful collection.

Laurie Klein says

Glynn, forgive me, I am late to the party. I hadn’t realized you’d already posted this. (Thanks, too, for posting on Amazon!)

I too was arrested by that triangular shadow you describe.

I am so grateful for your observations and responses, and for the time and care you’ve taken with my collection. And for this: What an elegant, generous, powerful closing line!

“But we cling to the living, and we cling to the loss, and we’re human for knowing both.”