For May Swenson, poetry was a box to unwrap

“A characteristic of all poetry,” poet May Swenson once wrote, “is that more is hidden it in than in prose. A poem, read for the first time, can offer the same pleasure as opening a wrapped box.” The pleasure, I suspect, was in both the anticipation and the discovery.

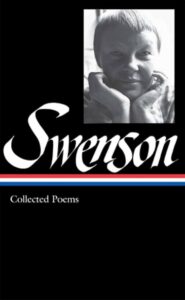

Swenson (1913-1989) is considered a major poet of the 20th century. She published nine collections during her lifetime; three additional collections were published posthumously. Her poems were widely published in literary journals and magazines. She received a bevy of awards, ranging from the American Introductions Prize in 1955 to Guggenheim and MacArthur fellowships. For the last nine years of her life, she served as chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. She also translated and published a volume of poems by Tomas Tranströmer.

May Swenson

Library of America published Swenson’s Collected Poems in 2013. The volume includes all of the collections published during her lifetime; a considerable number of her poems published posthumously; selected writings about poetry; and selected “iconographs,” or poems graphically displayed to illustrate the subject or theme of the poem. She explained her iconographs by saying the material and the “mold” evolved together to become a symbiotic whole. In 1970 she published a collection of these poems, aimed primarily for children, but similar poems are scattered throughout her published volumes.

The primary value of a volume like Collected Poems is to display how Swenson’s poetry evolved and changed over time, and how it remained the same. She was very much a proponent of “write in the present” or about current events, and a considerable number of poems are about different stages of NASA’s space program in the 1960s and early 1970s. You might expect these poems to be dated, and you would be wrong. Yes, they’re about events that happened 50 and 60 years ago, but in Swenson’s hands, they transcend their immediate subjects.

She wrote about every conceivable subject — family, nature, current events, time, emotions, self-discovery, travels in the western United States, and more. If there is one idea these collected poems suggest, it is that Swenson was a poet with a restless mind and imagination. She writes in arresting ways, using language to explain the immediate subject or theme but then making the poem about more than what it seems at first to be about.

One of the most moving poems in the entire volume is “In the Bodies of Words,” published in the collection In Other Words (1987). It’s dedicated to fellow poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979) and was composed a week after Bishop’s death in Boston in 1979. Bishop and Swenson were contemporaries, close friends, and maintained an extensive correspondence. More than 200 Bishop/Swenson letters are in the Swenson Archive at Washington University in St. Louis, part of the largest collection of Swenson’s literary efforts. It’s a beautiful poem: “Your vision lives, Elizabeth, your words / from lip to lip perpetuated.”

I like Swenson’s more simple poems best. They illustrate what she meant by poems being like unwrapping a box. Watch how this poem moves from a preoccupation with the characteristics of aging to something almost transcendent.

My glasses are

dirty. The window

is dirty. The binocs

don’t focus exactly.

Outside it’s about

to snow. Not to mention

my myopia, my migraine

this morning, mist on

the mirror, my age.

Oh, there is the cardinal,

color of apple I used to

eat off my daddy’s tree.

Tangy and cocky, he

drops to find

a sunflower seed in

the snow. New snow

is falling on top

of the dirty snow.

Swenson was born in Utah, the oldest of 10 children. English was a second language; the family regularly spoke Swedish. She received a B.A. degree from Utah State University, taught poetry at several universities, worked as a manuscript reviewer, and then shifted to being a full-time poet. While most of her papers are in St. Louis, some are also housed at Utah State; until 2016, Utah State University Press sponsored a competitive May Swenson Poetry Award annually for an outstanding collection in English.

Collected Poems tells an important story, one of a poet who both helped shape and was shaped by poetry in 20th-century America. May Swenson died 35 years ago, but her words, as she said of Elizabeth Bishop’s, are “from lip to lip perpetuated.”

Photo by Hafiz Issadeen, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Leave a Reply