Poet Jeanine Hathaway startles as she plays with words.

Poetry speaks to us differently than both prose nonfiction and fiction. It’s older than the printed word, of course, recited and repeated long before language was codified into letters, spellings, and definitions. Even in its written or printed form, poetry stands apart, like the older, sole child of a previous marriage. And it’s the literary form that most readily changes when it’s read silently and read aloud.

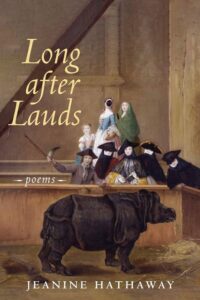

These differences between poetry and prose came quickly to mind when I read Long After Lauds: Poems by Jeanine Hathaway, published in 2020. And I will be an honest consumer. It wasn’t the poet’s reputation, or reading one of her poems in a journal or online, or the title that attracted me to the collection.

It was the painting used for the cover. I had seen it before, most recently last fall. And it’s just as odd when you study it in person as when you see it reproduced on a book cover.

The painting is Exhibition of a Rhinoceros at Venice (1751), with a group of mostly masked Venetians gazing at the armored animal. Painted by Pietro Longhi (1701-1785), the artwork is part of the collection in the National Gallery in London. What’s fascinating is that the animal, standing in patient solitude and munching on hay, seems more normal than the people observing it. It even bears the somewhat prosaic name of Clara, according to the poem (“Whose Expectation”) Hathaway includes in the collection.

Study it long enough, and the painting becomes startling, almost jarring. The same can be said of most, perhaps all, of the poems in Hathaway’s collection. You begin reading one of her poems, and what you think it’s going to be about might unexpectedly shift.

Several of the poems in Long After Lauds have the word “ex-nun” in the title, which sounds a bit more abrupt than “former sister” or “former nun.” Hathaway had published a chapbook in 2011, The Ex-Nun Poems, some of which might be included in this more recent collection. You meet poems with titles like “The Ex-Nun Volunteers on the Dig,” “The Ex-Nun Does Not Consider Rejoining,” and “The Ex-Nun Grows Restless Again,” among others.

No matter what former nun Hathaway is writing about, you’re in for a surprising ride. This is a poem that you might think is about aging, and it ends up with wordplay that invites you to reinterpret what you just read.

Near the End

of the Periodic Table, #79

bare ghastly elements

vastly attractive to

rejuvenating ads:

face filled in

by botulinum toxin

or spackle. Truss,

sling flab and that

floppy wobbleneck.

What droops firms

by goop, whitening

for yellow feet and teeth.

Sallow cheeks sag on

jaws not jowly;

hold their own classed by weight

as gold, we know, is. Atomic

Number 79. Pronounce aloud

its symbol, Au. Awww.

On another table, fill with awe

your bowl, the late fruit a little

soft on the surface. A windfall.

The symbol for gold is indeed Au. Pronounce it, and it seems something like what Hatahway indicates, “Awww.” But is that the shy, bashful sense of “Awww,” or is it the “Awww” that you cry in frustration? To add another layer of meaning, she adds a homonym, awe. Is she expressing awe at the realization that the Golden Years, like the “fruit a little soft on the surface,” can be about more than BT (or spackled?) facial treatments, sagging skin, and discolored teeth?

Jeanine Hathaway

Hathaway is a professor emerita at Wichita State University, where she taught writing and literature. She also served as a poetry mentor for the MFA program at Seattle Pacific University. In addition to her ex-nun chapbook, she has published an autobiographical novel, Motherhouse (perhaps drawing on her experience as a nun), and The Self as Constellation: Poems (2002), which won the Vassar Miller Poetry Prize.

No matter what subject Hathaway writes about in her poems, Long After Lauds is itself a kind of “praise of the ordinary.” Her poems require you to sit up and ask “Huh?” and then go back to reread them, preferably aloud. And you watch in wonder (awe, or perhaps “Awww” in the bashful sense) as she skillfully delivers images and metaphors than change even as you read them.

Related:

Photo by mislav-m, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Leave a Reply