In his own epic, John Rateliff documents how J.R.R. Tolkien wrote The Hobbit

I’m no Middle Earth scholar, but everything I know about J.R.R. Tolkien tells me The Hobbit was written carefully, over a long period of time, and regularly revised. Tolkien scholar John Rateliff documents precisely how that happened.

First, something of a confession. I bought Rateliff’s The History of the Hobbit last year, ordering it online. I was so excited I didn’t pay attention to the number of pages.

Including the index, it’s 938 pages. That doesn’t include the 41-page introduction.

To read a nearly 1,000-page volume requires determination and time. I had the former but not the latter. For several months, the book rested on my desk, almost staring at me in a kind of silent reproach. The only path forward in tackling it was the one I eventually followed.

I read it gradually and in spurts, until I could finally read it straight through.

He documents five phases of the writing and revision of The Hobbit. The first manuscript didn’t have a Gandalf; instead, the wizard was named Bladorthin. Smaug the dragon was originally Pryftan. Gollum doesn’t try to kill Bilbo; instead, he remains a faithful guide to the end. And there are other significant differences.

This first phase includes the “Pryftan Fragment” and the “Bladorthin Typescript.” Rateliff also notes that the original opening written by Tolkien has been lost.

The second phase is the longest section of the book. This is where the story that is most familiar to us took shape and involves most of the plot and character development. The third phase of writing and revision began when the story was set to typescript. This was the version eventually published in 1937. Ten years later in 1947, Tolkien made some revisions, proposing “corrections” to better align with the draft already under way — The Lord of the Rings trilogy. In 1960, the date of the fifth phase, some revisions made their way into a new edition of The Hobbit, and some found a place in The Lord of the Rings.

What emerges from this study is a writer who never “finished” the works he’s best known for, but instead kept editing and making small but important changes.

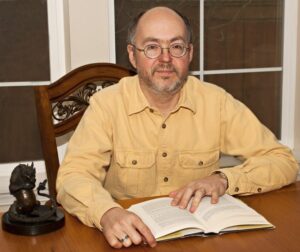

John Rateliff

The book is incredibly, and carefully, documented. The breadth of Rateliff’s knowledge and understanding is huge. This wasn’t a simple matter of comparing the different versions of a manuscript and seeing the notes in the margins. Instead, Rateliff examined notes, files, letters, biographies, histories, published articles, and studies.

Rateliff is an author, independent scholar, speaker, and creator of roleplaying games. For decades, he has specialized in the writings of Tolkien and presented numerous papers, published books, and given speeches and lectures. He also worked with Christopher Tolkien on History of Middle-earth, coordinating the holdings at Marquette University on Tolkien. He lives in the Seattle area.

This volume was published in 2023, the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death. Rateliff had previously published the two-part History of the Hobbit, Mr. Baggins and Return to Bag-End, and a one-volume edition of The History of the Hobbit in 2007. He also served as editor for The Rhetoric of Vision: Essays on Charles Williams.

If you’re a Tolkien scholar, The History of the Hobbit is a welcome addition to the literature. If you’re a Ringhead (aka Tolkien fan), the book is full of fascinating information about how Tolkien wrote his beloved story. Even if you’re neither, the book is a solid, well-documented account about how one of the most influential books of the 20th century came to be written.

Just remember to check the number of pages. At the very least, it will help you plan your reading.

Photo by Doug Scortegagna, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Bethany says

Fascinating indeed, thank you for this. I recognize John Rateliff from the behind the scenes appendices of the making of The Hobbit movie (for research). So glad you pointed his [massive] book out. And how interesting that Gandalf was at first not in The Hobbit! So glad Tolkien did add him, and endearing to know that Gollum was at first a faithful guide to the end. Hm, that makes me think about his character some more.