Laura Cumming has penned a deep reflection on growing up, art, and sudden death

Delft, The Dutch Republic, Oct. 12, 1654.

Imagine a quiet fall morning. It’s sunny; people are going about their usual activities. A painter, caught somewhere between down-at-heels and famous, is talking with his subject as he paints the portrait. A few blocks away, a clerk goes to the basement to check inventory, using a candle for light. The inventory is 90,000 pounds of gunpowder.

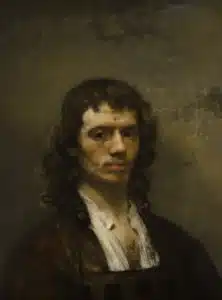

The explosion of what comes to be known as the “Thunderclap” levels whole city blocks. The sound is heard 70 miles away. Almost every building in Delft is damaged. Hundreds are dead; some bodies will never be found. Among the fatalities is the painter, Carel Fabritius, the only survivor of the people in his home but who dies a short time later. While he must have painted numerous pictures, what has survived is barely a dozen, including a few self-portraits. Some were likely destroyed in the explosion. One or two were misattributed to Rembrandt, in whose studio Fabritius had studied. But the fate of the rest is unknown.

The few we do have are astonishing. One is “The Goldfinch,” made famous to contemporary audiences thanks to another tale of an explosion, The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. A second is “The Sentry,” which could easily pass for an Impressionist painting 200 years later. A third is “A View of Delft,” a small painting likely done for a camera obscura and one which from childhood captivated Laura Cumming, chief art critic for the Observer in London.

That painting — how it was done, why it was done, and what it depicts — became the heart, and perhaps the soul, of Cumming’s latest book, Thunderclap: A memoir of art and life & sudden death. But the book is also much more. It’s a story about Cumming’s own family and especially her father, Scottish painter James Cumming (1922-1991). It’s about art in the Dutch Golden Age, roughly two decades in the middle of the 17th century. It’s a tale of how paintings can often be misattributed, until they are eventually cleaned, and the artist’s name discovered. And it’s the story of what happened in Delft that October morning, when so many people died, including a painter.

Carel Fabritius

It’s a marvelous, mesmerizing, and poetic story she weaves. And the work is filled with color reproductions of the paintings she discusses. It could serve as a concise introduction to Dutch 17th century art, and it is that, but it’s so much more. She’s telling the story of Fabritius and what little is known about him, and she’s telling a slice of her own story, of growing up with her painter father, the time they spent in Holland, and how she became fascinated with Dutch art, especially “A View of Delft.”

Laura Cumming

Cumming has been the chief art critic at the Observer since 1999. She previously published A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits (2009), The Vanishing Man: In Search of Velazquez (2016), and On Chapel Sands: My Mother and Other Missing Persons (2019). Earlier she worked for The Guardian, New Statesman, and the BBC.

Thunderclap is so well written that I’m inspired to read her other works, which were shortlisted for (and often received) other literary and arts prizes. This book also has received deserved accolades, being named a Top 100 Must Read Books of 2023 by Time and a Best Book of 2023 by The New Yorker, and shortlisted for the 2024 Writer’s Prize.

Photo by Pai Shih, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Leave a Reply