Edwin Arlington Robinson was the first great American Modernist poet

My favorite period of American literary history is roughly 1895 to 1940. As literary periods go, it’s a large swath of time, and it includes both the Realists and Modernists> (Perhaps it’s because I don’t see a clear delineation between those two schools of literature.)

For novelists, that includes Stephen Crane, Jack London, Willa Cather, Edith Wharton, Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and William Faulkner. My wife thinks I’m slightly crazy, but I’m one of the few people she’s ever heard of who enjoys reading Faulkner.

For poets, it’s T.S. Eliot, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Edgar Lee Masters, Vachel Lindsay, Robert Frost, and others — including Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935).

If I ask myself why this period is my favorite, I might answer by saying I really like the writers. I could also say it is these poets and novelists who most influenced the outstanding English teachers I had in middle school, high school, and college (not a bad or even mediocre apple in the lot). It’s not that I dislike later writers or contemporaries, or that I think literature has gone to rack and ruin. It is, I think, more about the writers I keep coming back to when I need to “center” or “re-center” my reading and even my mental and emotional states.

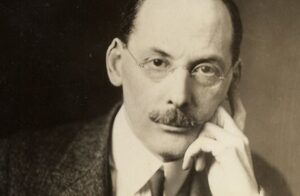

Edwin Arlington Robinson

In short, I find these writers calming, even in their often stark and unsympathetic depictions of life and people. Consider Robinson.

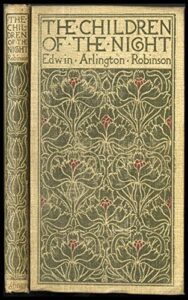

He was, and wasn’t, the proverbial overnight success. A Maine-born poet struggling to make it in New York City, he scraped together enough money in 1896 to self-publish 500 copies of his first collection, The Torrent and the Night Before. He hoped to give a copy to his ailing mother, but she died a few days before the published copies arrived. His second volume, The Children of the Night, was traditionally published in 1897. It caught the attention of Kermit Roosevelt, son of the then vice-president, who told his father about it. Teddy liked it so much that he eventually offered Robinson a job in the New York Customs Office, one that allowed Robinson to write almost full-time.

The poet’s reputation grew steadily. By 1920, he was one of the most read poets in America. In the 1920s, he received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry three times, including the first ever awarded for a poetry book in 1922. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times. He wrote two plays. Between his last Pulitzer Prize in 1929 and his death from cancer in 1935, he published seven more poetry collections.

Two of his poems were commonly taught and included in anthologies during my school years. “Miniver Cheevy” was published in 1910 as part of his collection The Town Down the River. But it was a poem he published in that 1897 volume, The Children of the Night, that is likely his most famous.

Richard Cory

The cover of the first edition

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,

We people on the pavement looked at him:

He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed,

And he was always human when he talked,

But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

“Good-morning,” and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich—yes, richer than a king—

And admirably schooled in every grace:

In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat and cursed the bread;

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night,

Went home and put a bullet through his head.

Robinson was known for getting inside the heads and the lives of the people he wrote about. “Richard Cory” reads almost like an epitaph; you might expect to find it in Edgar Lee Masters’ 1915 book Spoon River Anthology. “Miniver Cheevy” has a similar feel; you might think Masters evokes Robinson in his famous anthology, and you wouldn’t be wrong.

His poems often have haunting lines, seemingly pulled from real-life experiences. In “Old Trails,” a poem in The Man Against the Sky (1916), the poet by chance meets an old friend in Washing Square in New York City. The friend has not been a successful writer. “Behold a ruin who meant well,” he says. “My dreams have all come true to other men.” It is a poem about fame and success, how elusive it is, and what can happen when one gives up a dream.

Many of the volumes of Robinson’s poems are post-copyright and easily (and rather cheaply) accessible. Many are available in both e-book and print versions. There’s also a well-regarded biography of Robinson published in 2007 by Scott Donaldson (for some strange reason, it’s considerably cheaper in the print version). I read a Kindle version of both The Children of the Night (free), and the Delphi Project edition of his works and plays (at $1.99, a bargain).

Robinson was a poet who believed he was put on earth to do one primary thing, and that was to write poetry. And he wrote some astoundingly beautiful poems, ranging from his fictitious town to Arthurian legends about Merlin and Lancelot. He had a major and lasting influence on poetry, and he is still well worth reading today.

Photo by alvaroreguly, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

Leave a Reply