For Ben Okri, even the darkest stories are about hope

Standing in Hatchard’s Bookstore on Piccadilly Street in London, I’m looking through the shelves of poetry. Hatchard’s is the oldest continuously operating bookstore in London, having opened in 1797. It’s next door to Fortnum & Mason, and across the street from the Royal Academy of Arts. The Ritz Hotel is one block west, while Piccadilly Circus is two long blocks to the east.

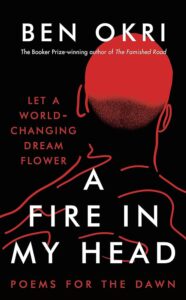

Hatchard’s poetry section is not huge, but it’s sizable, larger than what you find in most American bookstores. A small table display of books occupies the space in front of the shelves. Perhaps it’s the striking black, red, and white color design, but one volume draws my eye — A Fire in My Head: Poems for the Dawn by Ben Okri. The cover contains a sentence: “It was like a burnt matchbox in the sky.”

Okri has had a long and distinguished career as a novelist; he received the Booker Prize for his novel The Famished Road in 1991. He’s also written several collections of essays and short stories, a play, a movie script, a few television scripts, and several collections of poetry. With all of his writings and accolades, he says he considers himself a poet. He’s laid claim to inventing a new poetry form, which he calls the “stoku,” a cross between a short story and a haiku.

A Fire in My Head is his most recent volume of poetry, published in 2021. Its 43 poems occupy 139 pages. Some critics have described his poems and writings as “magic realism”; Okri describes that characterization as “lazy.” Perhaps a better description would be to say Okri is a poet who tells stories, and he often tells them in unusual ways. Here is how he describes his native Africa (he was born in Nigeria).

Africa Is a Reality Not Seen

a dream not understood

its wars are the scab of a wound

its famine the cracking of seeds

its dictatorships a child torturing

beetles in the field.

its soul’s older than atlantis

and like all things old,

it’s being reborn,

and doesn’t know it.

countless cycles of civilization

and destruction are lost in its memory

but not in its myths.

africa is a living enigma

an old woman taken for a child

a wise man taken for a fool

a beggar who is also a great king.

The collection contains two long poems, and they may be the most arresting in the collection. I found myself reading and rereading them several times. One is entitled “Saved Head Poem,” a deep and often moving reflection on civilization and where it may be headed: “we have refused to face / the dark truth that our civilisation / has become the greatest / threat to our civilisation.”

Ben Okri

The second long poem is one his best known, garnering 6 million views on Britain’s Channel 4 Facebook page. This is the poem that likely inspired the collection’s title and that cover sentence. “Grenfell Tower, June 2017” is Okri’s response to the tragedy of a high-rise fire in North Kensington in 2017, in which 72 people died during the 60-hour fire fed by the thermal insulation in the building. Many of the residents were immigrants or descended from recent immigrants. Okri’s poem captures the tragedy and, like most of his poems, offers hope for something better.

Okri has received numerous honorary degrees and awards for his writing, including the Commonwealth Writer Prize, the Aga Khan Prize for Fiction, the Guardian Fiction Prize, the Order of the British Empire, and many others. He received a knighthood in King Charles III’s 2023 Birthday Honours for services to literature.

The poems in A Fire in My Head also tell stories; most are considerably shorter than the two long poems. He writes of love; freedom; the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis; how a man finds himself in Boko Haram, the terrorist military organization in Nigeria; the Rohingya people in Myanmar; and other topics related to human rights. But Okri is ultimately and always a poet of hope, no matter how dark the subject he’s describing.

Related:

Ben Okri on writing his Booker Prize-winning novel The Famished Road

Ben Okri reads “Grenfell Tower, June 2017”

Photo by Photonoumi, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Leave a Reply