Osip Mandelstam turned Russian poetry on its head

Imagine waking up one morning to discover that a collection of your poetry has been published in another country, without your permission and in a mixed-up order you never would have approved. That’s what happened to Russian poet Osip Mandelstam; his second poetry collection, Tristia, appeared in Germany in 1922, via a friend who had the poems published.

It was beginning to be a dangerous time for Russian poets and writers. The Russian Civil War would continue for another year, although the Bolsheviks were in control of large swaths of the country, including Moscow and St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd and soon to be renamed Leningrad). Mandelstam was in something of a double bind; not only was he a poet, he was also from a suspect social class. He was born in 1891 in Warsaw. His wealthy parents owned a prosperous leather manufacturing business, and his father won the privilege of being allowed to live in St. Petersburg. That’s where Mandelstam grew up and was educated.

Influenced by the Symbolists, he published his first poems at age 17. He and his friend Anna Akhmatova eventually went their own way and associated with another group of poets under the general umbrella of the “Poets Guild.” His friends and fellow poets recognized his poetic genius; his use of language and metaphor in startling new ways attracted broad admiration.

Everything changed with World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the Civil War. Mandelstam might have left the country, but he elected to remain. His publication of poems stopped. He was arrested in 1934 for reciting an anti-Stalin poem to his friends but was released through the influence of Nikolai Bukharin. But he was arrested again in 1938 and sentenced to five years of labor. He died a few months later in a transit camp near Vladivostok. His widow, Nadezhda Khazina, held on to his writings and manuscripts.

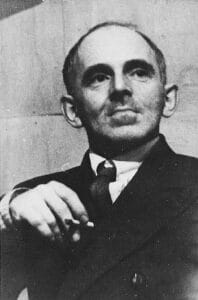

Osip Mandelstam

An edition of Mandelstam’s collected poems was published in 1964 in the United States. Nine years later, an edition was published in Russia. When the policy of glasnost was introduced under Mikhail Gorbachev, Mandelstam became one of the most popular poets in Russia. And so he has remained.

This new edition of Tristia is translated by writer and translator Thomas de Waal. De Waal studied Russian and Modern Greek at Oxford University, worked as a journalist in Russia in the 1990s, and published four books about the Caucasus. He currently works for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, D.C.

The Russian and English versions of each the 42 poems in the collection are positioned on facing pages. The titles of the poems are numbers, from 1 to 42. They were written between 1916 and 1920, bridging some of the tumultuous years in Russian history.

Some of the poems address that history, but Mandelstam doesn’t limit himself to that alone. He writes about peace and war, and he also writes love poems. He writes of his mother’s Jewish faith. His subjects include the city and spirit of St. Petersburg, Greek culture and mythology, Moscow, time and the seasons, the Crimea, music concerts, and more. Even in English and more than a hundred years later, the poems still resonate

This poem, written in 1920, is one of Mandelstam’s best-known works. As translator de Waal notes, it affirms the values of St. Petersburg culture “despite the onset of Soviet might.” It also affirms the value of poetry in the face of oppression.

No. 35

as though we’d laid the sun in its cold earth,

and for the first time we will utter

the blessed and the senseless word.

In the Soviet night’s dark velvet,

the velvet of a world entombed,

the eyes of blessed women are singing,

and immortal flowers still bloom.

The wild cat spine of the city arches,

on the bridge stands a patrol,

an angry motor growls in the darkness

and rushes by to screech a cuckoo call.

To pass through this night I need no permit,

the sentinels present no fears,

for the blessed word, alive and senseless,

in the Soviet night I offer prayers.

I hear a light theatrical rustle

and how a girl softly exclaims,

a huge pile of deathless roses

is laid in Aphrodite’s arms.

We warm away our boredom by the brazier,

maybe whole centuries will pass,

and in their arms the blessed women gather

the gentle embers and light ash.

The tiered finery of the boxes,

the red flowerbeds of the stalls,

an officer’s doll wound up by clockwork—

no scene for canting sinners of black souls …

Blow out our candles, if you wish to,

in the world’s dark velvet emptiness.

The women’s steep shoulders are singing

and you won’t notice the night sun rise.

Today, Russians consider Mandelstam one of their greatest poets. His poems capture something intrinsic to the Russian soul and psyche, a love for country and an idea that will often wreak suffering and even death upon those who express that love. This new translation of Tristia will bring an appreciation of Mandelstam’s poetry to a new generation of readers.

Related:

Poets and Poems: Osip Mandelstam and “Poems”

Photo by Raita Futo, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Ben Palpant Talks with 17 Poets About, Well, Poetry - April 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

Leave a Reply