We owe a great deal to the Roman poet Seneca, Dana Gioia says

I took two years of Latin in high school. Even (way back) then, Latin was a dying subject. Nine of us took Latin I. Five of us took Latin II. That was out of an all-boys public high school of 2,000 students. Our Latin teacher was passionate about the language; I can still vividly remember him almost bouncing as he paced in front of the blackboard, always holding a piece of chalk.

I learned more about English grammar in my Latin classes than in any English class I took. I also unexpectedly learned about the history and literature of Rome. That was because we translated sections of the writings of famous Romans like Julius Caesar, Virgil, Cicero, and a Roman born in Spain named Seneca.

Ancient bust of Seneca

Seneca, or Lucius Annaeus Seneca (the Younger), was a Stoic philosopher, poet, playwright, satirist, and, surprisingly, advisor to the Roman emperor Nero. To Seneca’s credit, he was more influential with Nero in the first five years of emperor’s reign; eventually, accused of involvement in a conspiracy to assassinate Nero, Seneca did what many well-known and suddenly-out-of-favor Romans did and committed suicide. I once thought this was a rather extreme practice, but suicide meant the individual’s estate would remain with the heirs and not be confiscated by the state. And the times were such, and the emperors were such, that most of the best people often ended up doing that.

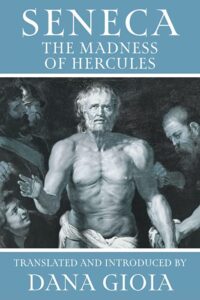

Under Nero’s predecessor Claudius, Seneca was exiled to the island of Corsica. It was a generally miserable experience, but Seneca apparently made use of his enforced leisure by writing plays, likely including one entitled Hercules furens, or The Madness of Hercules. Poet Dana Gioia has published a new translation under the general title of Seneca: The Madness of Hercules. It’s an excellent work, not only for the quality of the translation but also for the outstanding introduction to Seneca, his life and work, and his lasting influence.

Seneca’s story about Hercules is a tragedy in verse form. The man has just completed his 12 labors, and completed them successfully, when he’s confronted with a new threat. A usurper has overthrown the legitimate king of Thebes and is pressuring Hercules’s wife to marry him. Because we have a Roman play that has some Greek influence, the gods have a hand in all of this. Juno, especially, is outraged that Hercules, the illegitimate son of her husband Jove (Jupiter), has succeeded in his labors and now stands on the threshold of being made a god himself. She decrees that his very success will lead to the destruction of his own family and his eternal sorrow. Without giving away too much of the plot, that’s what happens. Here’s Juno laying out Hercules’s fate:

For Hercules—“May he return home safe,

His strength intact, and find his little sons

Happy and healthy.” Why resent his vigor?

I want him strong today. I want the same

Great force that conquered me to be his conqueror.

I crave occasion to applaud this hero,

Who triumphed over death’s dominion.

As he begs for death and grovels for oblivion.

And if I haven’t always been a good

Stepmother to my husband’s gifted son,

Today I’ll make amends. I’ll stand beside him

When frenzy blurs his sight. And help him send

Each arrow to its unsuspected mark.

I’ll be his staunchest ally in the fight.

And when he finishes his giddy slaughter,

I’ll have him raise his dripping hands to Jove

And ask for his admission into heaven!

My surprise in reading The Madness of Hercules was to see how much it reminded me of William Shakespeare’s plays, especially Hamlet. This isn’t a coincidence, as Gioia points out. Shakespeare read Seneca, whose writings inspired several of Shakespeare’s tragedies and histories. And it wasn’t only Shakespeare who was influenced. Others included Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe, Miguel de Cervantes, Dante, Erasmus, Chaucer, Petrarch, and even the Protestant theologian John Calvin.

Dana Gioia

Gioia’s introduction is so good that it deserves its own review. It concisely explains Seneca’s major influence on Renaissance writers and European culture; the man’s life and works; how Seneca figured in Roman life, history, and politics; his writing style and use of lyric poetry; and his legacy. Even in our own more jaded times, when anything older than 15 minutes is considered seriously outdated, Seneca’s influence continues, even if we’re not aware of it.

Gioia is the former poet laureate of California and chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. He received his B.A. and M.B.A. degrees from Stanford University and his M.A. in comparative literature from Harvard. He worked in business marketing for 15 years before becoming a full-time writer. He’s published five poetry collections, four books of criticism, and four opera libretti. The recipient of numerous awards and recognitions, he’s also received 10 honorary doctorates.

Seneca: The Madness of Hercules is one of those rare works, succeeding as history, biography, literary criticism, drama, and poetry. It’s a marvel, and Gioia has accomplished something important here, reminding us why we study the past, including the literature of the past, and why the past is never really the past.

And I have hope for Latin. My grandsons attend a classical education school where Latin is taught to all students beginning in the third grade.

Related:

Dana Gioia and “Meet Me at the Lighthouse”

Photo by Pai Shih, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Peter Murphy and “You Too Were Once on Fire” - October 14, 2025

- “Your Accent! You Can’t Be from New Orleans!” - October 9, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Vorreyer and “Unrivered” - October 7, 2025

Leave a Reply