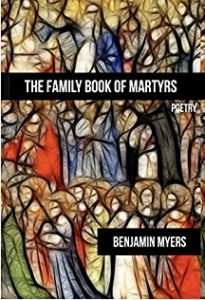

Benjamin Myers looks at our fears, our hopes, and what we love

If I were asked to list my Top Ten favorite contemporary poets, I wouldn’t hesitate to include Benjamin Myers, a professor of literature at Oklahoma Baptist University. Myers’ poetry deeply resonates with my own history and understanding of the world. I can’t explain why, exactly. It’s not the familiar condition known as “echo chamber.” But his poems do seem familiar in a deep, personal sense.

I discovered this when I read his Elegy for Trains (2010) and Lapse Americana (2013). But it was his Black Sunday (2019) that really punched it home. With its poems about the Oklahoma Dust Bowl of the 1930s, I found myself not that far away, in northern Louisiana in the 1930s, reliving my own family history. And that’s the key — I can’t read his poetry without revisiting my own family.

Benjamin Myers

His new collection, The Family Book of Martyrs, does exactly that. A relative uses his pellet gun to scare the dogs from doing their business in his yard; my uncle (by marriage) would sit on his back stoop with a .22 rifle, taking pot shots at the cats daring to leap over his fence. The cats belonged to the next-door neighbor, who happened to be his oldest son’s in-laws. And Myers writes about his grandfather’s workshop, sitting dusty and no longer used. The workshop of the grandfather I never knew sat silent, dust-covered, and unused; it told me two things, that he was a good carpenter, and he had a penchant for drinking things that came in glass bottles.

That’s what these poems do. Myers moves you from his words on his page to your life in your memory. It’s not an easy feat. The epiphany comes when you realize he’s writing about the things in life that matter — not the latest outrage from Washington or the latest viral craze on TikTok, but family, work, love, faith, children, spouse, the people who have come before you, and the people who will come after. It’s your hopes and your fears, which are often the two sides of the same coin. And Myers displays a sense of understanding — and, with that, gratitude.

Historical Markers

a need to know that drove us nuts and slowed

our progress toward the lake. We stood in sweat,

lurking like hitchers by the asphalt road.

The Battle of the Washita; the birth

place of Will Rogers; any church or shoot-

out that one might say mattered stopped us cold

beside the crumbling shoulder of old Route

66. So I’d drag my teenage self

out of the car to nudge the shoulder rocks

with white-toed Converse tips and stand there half

enthused while trying to look bored. Those talks

about the past beside the highway strip

are past now too, my father gone, the darker

years since a road I drive as it gets late,

squinting into the dusk to find a marker.

Myers has published four poetry collections and a book of poetics and has written numerous articles, essays, and reviews. His poems have been published in Image, The Yale Review, Modern Age, Measure, The Christian Century, and other publications. From 2015 to 2016, her served as the poet laureate of Oklahoma. He also directs the Great Books Honors Program at Oklahoma Baptist University.

I read The Family Book of Martyrs, and I think of my own family. I remember family vacations and how we never stopped for historical markers; we were lucky if my father stopped for a bathroom break (my mother never forgot, or forgave, that “drive in Tennessee”). I think about my aunt’s made-from-scratch biscuits, my uncle shouting at the Lawrence Welk Show, and my grandmother, sitting quietly on a Saturday night, writing the lessons for her Sunday School class in her little black-leather notebook. I watch my grandsons shoot hoops with all the grit and determination of aspiring professional basketball players.

And I feel gratitude. That’s what Benjamin Myers and his poetry evokes.

Related:

The Submerged Depths of Lapse Americana

Benjamin Myers and Black Sunday

Pinocchio in Nineveh: Benjamin Myers and Elegy for Trains

Photo by Andrew Kuznetsov, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Luci Shaw and “An Incremental Life” - April 3, 2025

- Ben Palpant Talks with 17 Poets About, Well, Poetry - April 1, 2025

Leave a Reply