Is It Okay to Write a Plot Without Conflict? (And Still Make a Good Story?)

Jump to The Day Before Tomorrow, a short story by Sara Barkat

I was recently playing We Become What We Behold: a game about news cycles, vicious cycles, infinite cycles by Nicky Case. Spoilers for the game—I didn’t realize until halfway through that you, the clicker, were “snapping pictures” of what was going on in society; in other words, you were playing as the news media.

The little prompts would say things like ‘gotta catch them doing *something* interesting. The game said it would take five minutes to play, but it took me far longer, because for quite a while I played it purposefully avoiding the sensational moments.

I was wondering when it would turn into a study of vicious cycles but finally realized that as long as you didn’t start anything you could live in an idyllic paradise forever. Definitely not realistic, that, but interesting to note that the game never forced you, the player, to escalate things.

Instead, the more you escalated things, the more your remaining options for what to “view” in society were curtailed; in search of ever-growing violence, you would hype that up, which would influence the new societal baseline to be that much more depressing.

prompt from Nicky Case’s web game, We Become What We Behold

It got me thinking about what it means to prioritize narratives of violence. Now, I firmly believe that people should be able to prioritize whatever kind of narrative they personally want—but the news-cycle machine and even algorithmic popularity always reaches for views above all else. Because it’s based on the principles of clickbait, it doesn’t really matter what people are actually interested in; what matters is getting that instant autonomic nervous system response.

For instance, I could say, “violence and violent stories are an important part of the human experience and people should be able to interact with that on their own terms, without being demonized for it,” or I could say “people who read about murders are evil!” Which one would get more clicks?

Hmm.

But enough about that. What the game really made me think about was how, as much as we would like to be independent agents floating in a Platonic ideal of rationality, we all exist in the time and place that we exist. We remain individuals with unique preferences, but the scope of how that plays out—your options within society—are of course limited by the surrounding conversations being had. And not only conversations—but on a much deeper and more unconscious level—the underlying assumptions.

For instance, the underlying assumption in “We Become What We Behold,” played out through the prompts, is that the only thing people will notice or care about is violence. And not only violence, but a very specific subset of violence. That is, interpersonal conflict. This makes sense—as the game is trying to emulate the news cycles these days; and that is what news tends to assume.

But it was those little prompts that really caught my interest. The idea that the only “interesting” and valid way of seeing the world would be one focusing on conflict.

Those prompts served as, in some sense, the internal voice of the newsperson, or the newsmakers, or even the clicker. Who would play a five-minute game about violence and spend probably the first five minutes happily clicking on a bunch of happy people? Absolutely no one, the unconscious of the newsmedia says.

“Good news is no news.”

Writers agree, say booksellers who want to sell writing tips. Search up any Novel Writing 101 and the first thing on that list will be “make sure you’ve got a conflict” and “every plot needs a conflict.”

The basic genre convention of the “successful story” is one that goes pretty much like this:

1) inciting incident

2) plot picks up steam, character has to fight something

3) climax, involving a showdown with the big bad

4) resolution.

In this structure, the plot is frequently visualized as a hill.

plot hill, drawn by Sara Barkat at age 13 after reading far too many books about writing

So far so good…how about zooming in to specific scenes? What is the common knowledge there?

“Every scene needs a conflict, usually between two people.”

Or, what? It’s boring? It fails at being a “successful” story? We throw it out of the conflicted story awards, to forever be banned from novel-writing feasts like Grendel in Beowulf?

The truth is—and this gets eclipsed in the “common knowledge” about writing stories, is that what every scene needs isn’t necessarily conflict. It’s momentum.

Now, conflict is a very easy way of creating momentum. But momentum can also be created in other ways.

In horror, many times that momentum comes from slowly revealing the truth of something—perhaps where we the readers start to know what’s going on before the characters even do.

In humor, momentum can come from a gag that increases in complexity every time it’s referred to, again through the careful dispensation of information at appropriate moments.

Momentum can also come from building up a sense of place and character, something that’s seen far more often in 19th century literature, which expected its readers to have an actual attention span.

That’s all well and good for scenes, you might say. It even makes a bit of sense. But plots always need to revolve around conflict. Usually interpersonal ones. I certainly couldn’t conceive of an alternative. Because no matter how you create your plot, your underlying unconscious—the options for how you’ve seen it done before—will probably keep sneaking in those old Hollywood ideas.

You might not have even heard about the plot without conflict—up until recently, the English Internet barely knew such a thing existed. It’s actually called “Kishotenketsu.”

Commonly translated as a “plot without conflic” this is a bit of a misnomer. Of course it’s not really stories about nothing bad happening, ever. But what it also isn’t is that basic Western plot structure that revolves around two or more people getting into an epic argument (sometimes involving murder). Carla Ra describes it persuasively as “it’s not the plot that does not rely on conflict, but its structure.”

It seems almost impossible to imagine, at first. Okay, the structure doesn’t have conflict. What does that even mean?

The introduction (kiku, in Chinese) is, as the name suggests, the setting: presentation of the characters, era… you know, the important components of your story.

“The development (shoku) is where the narrative advances. The events of your story start to unfold, setting action in motion.

“The twist (tenku) is when things get interesting. So far, the narrative was rising steadily. The Western audience may expect a climatic event to happen, but instead the twist changes the direction of the plot, and it presents the story in a new light. Can the twist be caused by an inciting incident? Yes. But it is not always the case.

“The conclusion (ketsu) is the end of the story. It usually ties the two directions together.”

—Carla Ra

This twist, or change, is a complex element I’m still not sure I’ve got a handle on, and it’s been touched on in articles like this one.

Of course, being a writer, what I wondered was “Can I actually make that happen in a story?” Sure, it’s very popular as a structure in China and Japan, but I wasn’t at all sure I could even wrap my mind around how a story with those beats might play out.

The significance of plot without conflict by still eating oranges—probably the premiere (and certainly one of the first) explanations of the subject on the web—explains it in terms of four-panel comics, but that’s very different from a piece of writing. Even though I read many interesting articles about kishotenketsu, I couldn’t put my finger on what that kind of structure might actually look like until I saw someone comparing it to the structure of urban legends.

You can un-hide this creepy urban legend The Licked Hand by clicking the button. 🙂

A very young girl is home alone for the first time with only her dog for company.

Listening to the news, she hears of a killer on the loose in her neighborhood. Terrified, she locks all the doors and windows, but she forgets about the basement window and it is left unlocked. She goes to bed, taking her dog to her room with her and letting it sleep under her bed.

She wakes in the night to hear a dripping sound coming from the bathroom. The dripping noise frightens her, but she is too scared to get out of bed and find out what it is. To reassure herself, she reaches a hand toward the floor for the dog and is rewarded by a reassuring lick on her hand.

The next morning when she wakes, she goes to the bathroom for a drink of water only to find her dead, mutilated dog hanging in the shower with his blood slowly dripping onto the tiles. On the shower wall, written in the dog’s blood, are the words “HUMANS CAN LICK TOO.”

—text from The Licked Hand on Wikipedia

The Redundant Character shall now speak, in a complete understandable way:

Do you like plots without conflict? Plots without conflict don’t have conflict the way plots with conflict do, but they’re still plots. Without conflict, you might think, nothing happens. But that’s not true. Plots without conflict are just plots, without conflict though.

Oh, that makes much more sense!

Now, I’m sure that I did a first attempt at this form in as basic a way as someone trying their hand at a ghazal for the first time, but I felt all of a sudden that I could at least figure out where to start in exploring the form. And, whether I was successful at it or not, the resulting story was still one that I ended up liking a whole lot:

The Day Before Tomorrow

It was autumn, during the days when the air was sharp enough to chew. Walking down the cracked asphalt road, Min kicked a cragged stone back and forth from one shoe to another. In between, there was the unmistakable sound of footfalls, muffled with the rubber tread, and there, the skittering of the stone, and the occasional wet smear of it sinking across a span of leaves, brown and veined and already worn down to shadows.

“How did you do on the test?” she said at last, in a tone of conversational nonchalance. She peeked at her companion, who was walking heedless of the chill in the same combination of T-shirt and jeans she always did.

“Dunno,” Pari replied.

“I wasn’t sure about the last question,” Min confessed. They stopped at the crossroads, and from that corner they could see down the curve of the street, the edge of the road marked with its zipping stark power lines, the immense curled swathe of trees broken intermittently by the pale painted sides of houses and spires. It was noon, and the sun was hot, so that in moving from the shadows under the trees to the open space Min felt a shiver even under her sweater and scarf.

“I think it was C,” Pari said. The girls stood for a moment, unwilling to go their separate ways. A car sped by round the curve with a rumble of noise and presence, and then everything subsided again. A leaf fell, and Min and Pari both reached forward to catch it, and missed. It twisted to the ground, and lay, a spark of orange at their feet.

“Come get ice cream with me?” Min said.

“At this time of year?”

“Why not?”

Pari shrugged. “Okay.”

They took the other turn, continued along the curve of the road that wound its way into town. Pari stuck her hands in her pockets. “Why do you think no one talks about it?” she asked, as though the question had been on her mind for a long time. “—Because they’re afraid?”

“Maybe?” Min said. She frowned, and as though both struck by the sudden, unfightable urge, they looked up—over the brick top of the water tower, where: it was. There it was. A mass of dark buzzing, an ink-drenched shadow, a pure midnight. It was, they knew, filled with the sounds of waves, but only the thinnest tendrils held it to the ground. It filled the whole eastern expanse. It covered the farthest reaches of the mountain. It held drops of water suspended in its reach, and the ground underneath it was ash and dead bones.

Pari swallowed. She looked away first. And Min, gazing, felt its sound, that sound that everyone knew, for it crept into their dreams: that endless beating pulse. It was closer than it had been even yesterday; or larger: she still recalled how the roads in that direction trailed off into melted rubble, a volcanic interruption.

“Maybe it’s angry?” she said.

“Does it get angry?” Pari said.

Min chewed on a strand of hair, an anxious habit. She looked away and smiled back at Pari. “Who knows,” she said. They laughed, and turned the next corner.

They were almost in the valley, now, and it was barely more than a spot of endless night, an unfathomable pinprick, like someone had punctured the sky. Blue shone, and the dappled light of the sun played over their sneakers.

By the ice cream shop, they read the chalked sign. Pari decided to get pineapple. Min got chocolate. They paid, and were then returned to the doorstep, ice cream in hand; Pari stuck her spoon into her cup and balanced on the curb. Min sat down beside her. In the emptiness under their feet, the hollows of the road’s intestines were filled with water.

Past went Mrs. Johnson, their teacher. They said hi.

“Did you hear that Patti broke up with her boyfriend yesterday?” Min said.

“Huh, really?” Pari asked. She flopped down beside her friend.

“Mm-hm,” Min said. “He was a jerk to her anyway, so it’s a good thing.”

“Daniel’s getting married,” Pari said.

“Wow.”

They finished their ice cream and threw away the cups and spoons.

“See you tomorrow?” Min said.

“If we’re still here,” Pari joked. Min knocked her with her elbow, laughing.

“Sure, I’ll meet you by the steps.”

In winter, everything was ice. It hung from the eaves in long, thick, glistening spikes, like a burning-glass for the weak sun. Min wrapped her scarf around her, put on her coat and mittens, and walked across the grey road. Aames, the neighbour, was using a snowblower. It cut through the silence; he looked down, concentrating, at the dusty whirl by his feet. The sound chased her down the street.

At the corner, by the steps, Pari was waiting. She had her hands tucked into the pockets of her jeans, boots on that she stomped, with concentrated precision, into the roadside slush. Goosebumps trailed their way across her bare arms, and when she turned to Min, the breath of her air made a clear puff that hung, suspended, and drifted away. “Hi, Min.”

“You should wear your coat,” Min said.

Pari shrugged. “Don’t want to.”

“Take my scarf at least?”

Pari shrugged, and took it, looping it around her neck. “I’m not cold,” she said.

“Still.”

“Do you think they’ll solve anything?”

“At this meeting?” Min frowned. “Well, they’ve got to start somewhere. That’s why it’s a town hall? Right?” Pari held out a hand and Min took it as they poked their way over sidewalks slippery with black ice.

They could hear the steady sound of water rushing by underfoot, under the cusp of the road. The manhole covers and the drains, full. When they walked by too slow, sometimes they could see just-a-bag-of-bones crawl out of it; a very long, tail-like creature with legs and no eyes or mouth, but a nose. It turned their way, sniffing, and they hurried into the lighted areas as dusk fell deeper over the town. It followed, its skeletal fingers dragging on the ground, like a scraping knife, but stopped at the corner of Main Street and wouldn’t come any further.

The town hall was lit up with warmth, gold light spilling out through the doors, the glass windows diamond-paned, reinforced by wires. Inside, they hurried to find seats in the girth of folding chairs spread out into an army of aluminum points. Pari sat down, jiggling her leg. Her hands twisted around the ends of Min’s scarf.

Jacob and Emily slid in beside them, at some point, Jacob pulling out a seat for Emily. She smiled at Jacob and kissed him, gently, on the mouth. “I hope they talk about the water,” Emily said, leaning away to flop onto a chair. “It’s been rusted for weeks. Hi, girls.” She put her purse in between her feet and fished around for a tissue to wipe the fog from her glasses.

“Hi,” Min said. Pari was leaning back, thinking about the long entry she’d added to her journal yesterday, her eyes closed to muffle the sound of people arriving, chattering, filling up the empty room with keys clinking and the scrape of chair legs across the floor. Min nudged her. “Emily and Jacob say hi.”

“Hi,” Pari said, eyes still closed.

Jacob flipped through a brochure for the new Rapid Water Adventure down the road. His chipped blue nail polish covered the image of a screaming group of friends in a log.

“Pari and I want to talk about the bone things,” Min said.

“Those?” Jacob said distractedly. “They’re harmless.”

“I know, but they draw in the alligators,” Min said. “And I really don’t want to get eaten by one of those.”

“True,” Jacob said. “You should mention that when you bring it up.” He stared down at the open brochure in his hand. Laugh like your life depends on it! it said. The people in the brochure had colorful shirts on and tans. They glowed with tourist-bound enthusiasm.

“It’s not even open yet,” Min said, following his gaze.

“Just wondering if there’ll be one of those big slides,” Jacob said. “The kids have been asking about it all week.”

Near the front of the room, the meeting was beginning. Jacob slid the brochure into the side pocket of Emily’s purse. The corner stuck up, making an odd, upside-down picture of someone’s sandaled foot, water tugging at the ankle.

In the spring, Rosa and Juan from down the block moved west—they’d heard it was nicer in the country.

It was a lowering cloud over the east, so that whenever Min woke up early in the morning from the birds’ racket, she could see it from her window behind the roofs of the houses. It was up against the water tower now, and its dark underbelly cast a shadow over the bulbous white roof. Sometimes she almost thought she could feel it, a vibration rattling her bones. Min could never tell if she wanted to leave her shades closed, and not have to look, or open them to let in the sun. Sometimes she left her shades open only a crack, and then the sunlight would steal in like a burning lance across the floor.

Min put on the new shirt she’d bought last weekend, with the magnolias on it. She put a yellow hair band onto her wrist, and then added a few more for good measure, in shades from blush to neon pink. She raced through two granola bars and called that breakfast, running to meet Pari in the park.

When she got there, Pari was staring at a roly-poly bug.

“Hi, Pari,” Min said.

“Hey,” Pari said. She was squatting on the ground, the ends of her jeans dragging in the mud. She poked her finger at the bug and it curled up. “Did you know they’re related to shrimp?” Pari said. “They have gills and everything.”

“But they’re on land,” Min said.

“Yup.” Pari looked up at her and grinned.

“How long have you been poking that thing?” Min asked.

“I dunno, since I got here,” Pari said. The bug had uncurled, a little grey knight in armor. Pari poked it again, gently, and it curled up, frozen in its fear. Pari stood up and dusted her hands on her jeans.

“I’ve never seen you wear that shirt before,” Pari said.

“It’s new,” Min said.

“Oh.” Pari nodded. She rocked forward on her toes. One shoelace, untied, fell around her blue and white sneakers. “Uh, it’s nice.”

“Thanks,” Min said. “I thought, since we were going to the movies later—” she stopped short, awkwardly. “Well. I mean. That makes it sound like a date.”

Pari shrugged. “If you like it, wear it.”

“That must be what you do all the time,” Min teased, smiling.

“I think I’ve got some nice clothes around,” Pari said. She paused. “Somewhere.”

They started walking. In the park, the green things were creeping up out of the dirt. The air had its own smell, Pari noticed. She tried to categorize it, to figure out how it was different from winter. Something fuller, perhaps. More in it. She came to this conclusion every year, but it still surprised her.

“Hey, Pari,” Min said at last, when they had been walking around an opening hydrangea. She spoke down, looking intently at the flowers. “Have you ever thought about it? Dating? Us, I mean.”

“Not really,” Pari said. “Why, do you want to?”

Min hesitated. She chewed her lip. “I don’t think so. I just had a feeling—well, maybe we should? Right?”

“Because…” Pari said.

“Because otherwise, we’re just—” Min fell silent, awkwardly. She stared at Pari as though she’d said something she didn’t want to, or maybe hadn’t said something she did want to. Pari’s eyes slid away as she thought. She looked at the frilled top of Min’s shirt, noticing the braid on it, a loop of machine stitching.

“Nothing wrong with ‘just’,” Pari said. “Is this about Patti?”

“Maybe,” Min sighed. She seemed more at ease now, and Pari decided she’d gotten it right. “She’s just been going on and on about how nice it is, now that she found Amy and they’re thinking about buying an apartment and, well, that’s all of us, isn’t it?” She counted on her fingers. “Daniel, Patti, Ethan, you and—and me. They’re off doing, well…” she shrugged. “What everyone does.”

“I don’t care about what everyone does,” Pari said. “If you wanna date so you can brag about it, we can. Or you don’t even have to date me. You could just tell everyone we’re doing it. It’s not like they’d be surprised.”

“Could I?” Min said, anxiously. “Just tell them, I mean. Without us having to be different, you know.”

“Yeah, why not?” Pari said.

“Good,” Min said. She smiled.

They walked a little further. At some point, the footpath crossed a small stream, only a few feet deep, planned and directed with nicely-placed stones at auspicious intervals. The water was still rusty. It flowed through, reddish and slow, and Pari dropped a few sticks into it and watched them sink.

Min sat by the edge of the bridge beside her friend, leaning her arms on the lowest bar and swinging her knees off the edge so her feet arced out over the water. The shadows of her legs were dark on the rippled surface.

It was summer, hot and dry. Even the air was sticky, and the grit in Min’s eyes never seemed to leave. She stood at the edge of the hill, realizing this would be her last view from the school, and she looked over the deep green sea of leaves, and the spires of the houses below. Beside her, Pari tapped the end of a smiley-face pencil against her jeans.

“Feeling victorious?” Pari said.

“I don’t think so,” Min said. “I don’t know what I’m feeling. I mean … you know?”

“Yeah,” Pari said. Without talking, they looked over at it.

It had moved, somehow. Imperceptibly, and scorched the ground around the water tower. It was close enough, now, that Min could hear waves all the time. They had tormented her throughout her timed essay, and she hoped she’d managed to write something that didn’t sound like a dead sea.

“What now?” Min said.

“I’ve got a car,” Pari said. “We could just…drive away.”

“Where would we go where it can’t follow?”

Pari pulled her eyes away, turning her back brazenly to the shadow. She stuck her pencil behind her ear. “Doesn’t have to be about it. Could be about us.”

“Hm,” Min said. She turned around, mirroring her friend’s posture, and watched their twinned shadows merge. “You mean, sticking together?”

“Of course,” Pari said. “I mean—” for the first time she seemed a little hesitant. “There’s no one else you want to stick with. Right?”

“Yeah,” said Min, softly. “Let’s go then.”

They walked down the hill. Stepping over the cracked asphalt, Min kicked a stone back and forth between her feet, and then aimed, sending it across the paved expanse and into the sere, soft grass.

my editor

are you aware this post doesn’t really have an ending?

me

kind of like the plot without a conflict. which also doesn’t tend to have endings where things are wrapped up nicely. instead, in part four, everything comes together and then says “bye.”

my editor

*blinks*

me

bye!

Photo by Erlend Ekseth via Unsplash.

Do you like plot without conflict? If you like to learn about plot without conflict, you might enjoy articles about communication like The Seven Principles for Making Friendships Work. Plot without conflict could also lead you to Poetry Prompt: Observations that Evoke. If you liked plot without conflict you might also like Perspective: The Poet Takes a Bike Ride.

Interested in plot without conflict? You might also like Poetry Prompt: How Do You Spell Communicate? If you like plot without conflict you might also like Reading Generously: Happy Endings. If plot without conflict was inspiring, you might be inspired by Teacher Stories—My First Villanelle. If you’re interested in plot with or without conflict, you might also like Winter Stars Book Club: Tragedy.

If this discussion of plot without conflict was exciting, you might also like Adjustments Book Club: We Note Our Place With Book Markers. In the spirit of plot without conflict, check out It’s Random Acts of Poetry Day and the World Could Still Use Kindness.

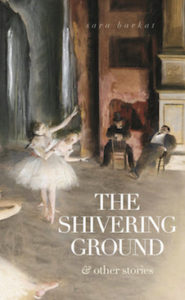

“Stunning…from start to finish. Barkat is a fierce new voice.”

- Good News—It’s Okay to Write a Plot Without Conflict - December 8, 2022

- Can a Machine Write Better Than You?—5 Best (And Worst) AI Poem Generators - September 26, 2022

- What to Eat With Dracula: Paprika Hendl - May 17, 2022

Bethany Rohde says

This is fascinating.

L.L. Barkat says

It feels like the kind of story you might like to write, Bethany.

(Isn’t it nice to know there are more story structure possibilities than popular advice might have asserted? 🙂 )

Bethany says

Thanks for the encouragement, L.L. Yes, it’s interesting to hear about other paths a writer might take. This is the first time I’ve heard of kishotenketsu.

Bethany R. says

Sara, I love the first sentence in the short story. And your use of kishotenketsu is interesting and instructive. In Part 3, I see how you used the twist of the relationship development, or rather, discussion of changing their relationship status, instead of a classic “conflict” through an alligator attack, flood, or by showing us what exactly that cloud can do to one of our main characters. And then in the last part, we find out that actually that both characters really want that development to happen, rather than just “bragging about it” or shrugging it off as no big deal. It makes the first three parts come together. The foreboding, anxiety-inducing (as demonstrated by the sucking on hair and jiggling leg) environment they are both living in helps us to see why the connection and companionship of Min and Pari might be even more appreciated and comforting. Thanks for this!

Also, I kinda love your ending of this post. 😉