Jack Bedell writes poems about the nature of south Louisiana

You grow up in a place like suburban New Orleans, and one of the first things you learn is that the land on which the suburbs float was at one time marsh or swamp. My own childhood home had two huge cypress trees in the yard, and they never did quite thrive like they did in marsh-days. The one next to the driveway died first, the cement partially blocking water from reaching its roots. A few years later, the one in the front yard died as well. Even in humidity- and rain-rich New Orleans, it needed more water than allowed by the St. Augustine grass.

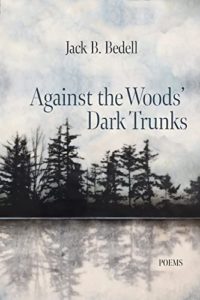

I thought about those cypress trees as I read Against the Woods’ Dark Trunks: Poems by Jack Bedell. Bedell is a professor of English and coordinator of Creative Writing at Southeastern Louisiana University in Hammond, which sits “across the lakes” from New Orleans, the lakes being Borgne, Pontchartrain, and Maurepas. It’s just up the road from Ponchatoula, which for a very long time laid a legitimate claim to being the strawberry capital of the world.

Bedell also writes about beached whales in Terrebone Parish, serpents and insects (of which there are a prodigious number, especially mosquitoes), folk legends (like the one whose name you never say, and I won’t say it here), pelicans (state bird), marsh horses, swamp phantoms, and the smell of the swamp (stinky). He even writes about a man (P.V. O’Neill) who’s buried in the ground, but he had to go all the way to Shreveport in northwestern Louisiana because the water table allows almost no below-ground burials south of Lake Pontchartrain.

He even writes about one of the stars of the Audubon Park Zoo in New Orleans.

The White Alligator

A white alligator (photo via Audubon Nature Institute, New Orleans)

The white alligator at the zoo

rests his head on top the water

with only his blue eyes showing.

He hangs his body straight down

like any of us would, floating,

does not miss the sun

burning his pale skin, the pull

of mud in cold weather.

He does not fret for need.

I’m sure when his lids nictate shut,

he dreams of water-green hide

and a deer’s total suppliance

nosing water from the bank’s edge.

What more could his slow smile want?

Jack Bedell

For the record, the white alligator is not, I repeat not, an albino. Albino alligators do exist, of course, but this white alligator is the rare leucistic alligator, aka Alligator mississippiensis. And you watched yourself around him, with those mesmerizing baby blue eyes of his. (Spots, the zoo’s white alligator, died in 2015. He was 28.)

From 2017 to 2019, Bedell served as post laureate of Louisiana. At Southeastern, he also serves as editor for Louisiana Literature and director of the Louisiana Literature Press. He’s published several poetry collections, including Color All Maps New, Rock Garden, No Brother, This Storm, Bone-Hollow, True, Revenant, and Elliptic. His poems have been published in numerous literary journals and magazines.

If you’re from south Louisiana, you settle in with a cup of coffee and chicory (and maybe a beignet from Café du Monde) and smile the entire time you read the fine collection that is Against the Woods’ Dark Trunks. Even if you’re not from south Louisiana, you learn a lot about a unique place in history and nature. But if you are, you can’t help but remember those cypress trees which shaded your childhood playtime.

Related:

50 States of Generosity: Louisiana

Photo by Kayaker Bill, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

Sandra Heska King says

That collection would be worth it just for the alligator.

Did you see the story about the guy who tried to smuggle the live albino(?) alligator in his suitcase on a plane?