Colm Tóibín tells stories in his first book of poetry

Vinegar Hill is two places representing two things. It’s the site of a battle in 1798 during the Irish Rebellion, in which Irishmen battled against, and lost to, the troops of George III. The site of the battle is just north of Wexford in Ireland, where Colm Tóibín would be born in 1955. And Vinegar Hill is the name of a neighborhood in Brooklyn, next to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, that had a large Irish American population (so large that New Yorkers referred to it as Irishtown).

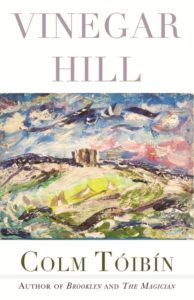

The title poem of the poetry collection Vinegar Hill published by Tóibín refers to the site of the battle. “We can see the hill from our house,” he writes. “It is solid rock in the mornings / As the sun appears from just behind it. / It changes as the day does.” His mother, taking art classes, is trying to paint the hill, but the hill keeps changing. And Tóibín, trying to describe the color, decides there’s no point in invoking history.

The collection has so many American-set poems, and the poet has so many American connections, that the title easily shares connections to that Brooklyn neighborhood. Both Vinegar Hills share the hopes and dreams of the Irish people.

Tóibín tells stories in his poems, which is not surprising, given his early journalism background and the number of novels and short stories he’s published. The poem “September” becomes a story about the pandemic and an elderly man wearing a mask. A poem about birds becomes a story about the approaching headlights of a car. Or the story about the time his mother played a prank on his young brother by dressing up as a nun. Or one about hitchhiking, which is a story about a family saying the Rosary. Even when the poems are more impressionistic than a straight story, they still have a storytelling feel.

And describing the shutters on a house becomes a story about something else entirely.

Blue Shutters

And they gave on to the street

From the first floor of the long

Building. In the July afternoon, when closed,

They unsettled shapes and textures,

Made things seem muted, unfinished, withheld.

Some family waited in the living room.

From that room, a curved stairway led

To a windowless landing. The second

Room to the right, overlooking

The courtyard, was the room where she died,

If died is not too strong a word.

We stayed with her in any case, were quiet

For a while, and then went down

And told the others what had just transpired.

I called the undertaker, shook someone’s

Hand, then crept up the stairs again

To find the body covered with a sheet

To protect her, I suppose, making clear

That this was where she was, had been.

It helped to keep her private and at peace.

Colm Tóibín

Tóibín (born in 1955) has published both fiction and nonfiction. His nonfiction includes The Trial of the Generals, Bad Blood: A Walk Along the Irish Border, Sign of the Cross: Travels in Catholic Europe, Lady Gregory’s Toothbrush, and All a Novelist Needs: Essays on Henry James. His fiction includes The South, The Heather Blazing, The Story of the Night, The Blackwater Lightship, The Master, Brooklyn, Mothers and Sons: Stories, and The Empty Family: Stories. His plays include Beauty in a Broken Place, The Testament of Mary, and Pale Sister. His work has been translated into more than 30 languages.

He’s taught at Princeton, Stanford, the University of Texas, and the University of Manchester. He’s currently Mellon Professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and Chancellor of Liverpool University. Tóibín has received numerous prizes and recognitions, including the Dublin IMPAC Prize, the Prix du Meiller Livre, the Los Angeles Times Novel of the Year, the Costa Novel of the Year, the Edge Hill Prize, and others.

If you’ve read Colm Tóibín, or seen the movies The Blackwater Nightship and Brooklyn, you know what a fine storyteller he is. Vinegar Hill continues and underscores that reputation.

Related:

Falling in Love with “Brooklyn”

Photo by Daniel Huizinga, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Leave a Reply