Beekeeper and Poet Sara Eddy Speaks Profoundly

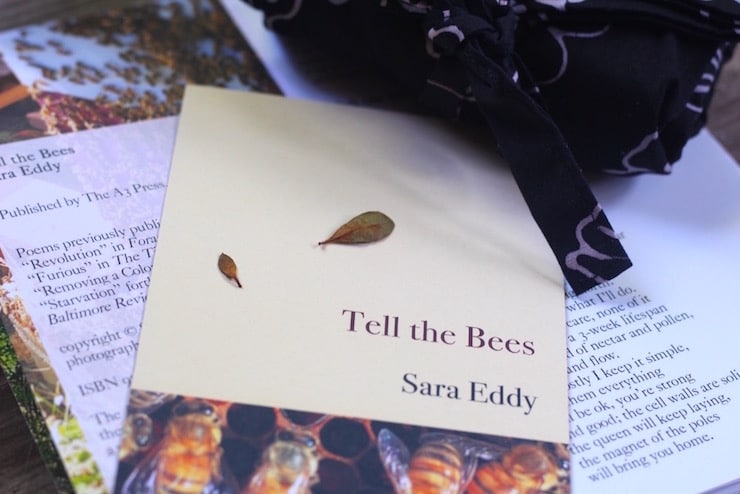

This year’s Tweetspeak Summer Lights Poet is beekeeper and poet Sara Eddy, whose work we found to be important, enriching, and profound.

We wanted to give her work greater audience, so we’ve spent the summer giving you an inside view of Sara’s work via posts, a live event, and poetry features in Every Day Poems.

Today, we’re delighted to interview Sara, to give you an even deeper understanding of her relationship to poetry (and the bees 🙂 ).

Interview with Poet Sara Eddy

L.L. Barkat (L.L.): You said in a recent event we did together that your “message from Mars” to start being a beekeeper was middle age itself. Can you say more about why beekeeping in particular? Why not bungee jumping? Or becoming a tea sommelier?

Sara Eddy (Sara): I had always been fascinated by bees: as I said in our discussion online, I used to lie in the grass when I was a child and dare myself to let them walk on my hand. I suppose that was part of a general Snow White fantasy, that all the creatures of nature would love me, and even bees wouldn’t sting me. But as I grew older and learned more about them, I got interested in their social structures, the beautifully balanced organization of the hive.

Bungee Jumping? Tea sommelier?

Maybe those are down the road! Actually probably not bungee jumping. But I really love a good cup of tea. Really, though, I think the next things for me are all kind of closely related to what we talked about in the reading: more time spent with my head in poetry, writing and editing, and more time in my garden. I’d like to keep chickens at some point, and I’d like to get more serious about my vegetable garden and the possibilities of permaculture on my little property.

LL: Did you have any inside conversations with yourself before taking the beekeeping plunge? Or, did others have opinions they offered? What did some of that sound like?

Sara: The conversations I had with myself about beekeeping had a lot to do with overcoming fears and self-doubt. I had wanted to do it for so long, and I suddenly wondered what was holding me back. When I looked more carefully at that, I realized I was scared I would fail, scared I wouldn’t be able to get the hang of all the complexities of it, and scared to claim for myself the time and energy required for a new hobby when I had young children to raise and a job and a husband. I was at a point in my life when it was important that I face those fears, so I did (hahaha as if that’s easy).

There’s a common aphorism among beekeepers that “people get into beekeeping for the honey, and they get out of beekeeping because of the honey.” Harvesting honey is labor: it’s sticky and time consuming and sweaty, and the equipment that makes it a little easier is expensive and has to be cleaned thoroughly (which is more work).

They also say that bees are “more work than a cat; less work than a dog.” At the time I started, though, I had a high-maintenance aggressive imperious cat, so that wasn’t helpful. As it all turns out, I still enjoy the hands-on labor of harvesting honey and taking care of them, even after 6 years. Most beekeepers aren’t poets, and they won’t tell you about the wild earthy smell of the hives or how you actually come to love them.

LL: I was fascinated by your explanation of why bees sometimes die over the winter (a sad experience you chronicle in your poem “Starvation.”) Can you say more about what leads to winter death for bees? Also, on the note of starvation, can you give us simple, maybe even unexpected, tips on how we can play a part in not starving the bees?

Sara: Winter hive death is a huge problem for beekeepers, and it’s gotten worse over the past few decades. In New England, one of the biggest factors is a parasitic mite called varroa, that attaches itself to the bees, drains their energy, and spreads disease. A hive with a varroa infestation usually loses a lot of bees, and they need a lot of bees to make it through the winter.

Really anything that weakens the hive at all can lead to winter losses, though: pesticides killing off some portion of the hive; mice getting in the hive, leading the bees to leave out of irritation; beekeepers taking too much honey; increasingly sterile cultivated grass lawns, which decrease the amount of foraging space for pollinators; spiking temperatures midwinter, which fool the bees into leaving their cluster. There’s more, too. Considering how frightened lots of people are of bees, they’re remarkably fragile.

What can you do?

• Decrease the size of the flowerless section of your lawn as much as you can, by planting pollinator-friendly gardens

• Consider planting creeping thyme, instead of grass.

• Wait until after the dandelions have bloomed in the spring, before mowing them off.

• Let white clover and violets and other low flowering plants live intermingled with your grass.

• Don’t buy plants that have been sprayed with neonicotinoid pesticides, which have been shown to damage hive strength and reproductive health in bees. If you use other pesticides, only use them in limited, focused ways, and only spray after dusk, when the bees have returned to their hives and won’t be on those plants.

L.L.: If you stopped being a beekeeper tomorrow, how would that change your life—and your writing?

Sara: If I stopped beekeeping tomorrow, I would miss them, but it probably would mean just a subtle shift for my life and writing. I know myself too well, to think that I’d go for long without replacing them with another passion-project. And for me, any deep, sustained engagement with the small cycles of the world leads to poetry.

L.L.: One participant in our recent event asked if you ever read TO the bees. You said that, to date, you have not. Are you considering it now? If you do it, what will you read and why?

Sara: If I were to read to my bees, I think I might read them bee poems by Plath or Dickinson. Somehow reading them my own stuff would feel weird—like giving a poetry reading for your family. Doable, but somehow the wrong audience. I sing to them all the time, though, and I often put music on my phone while I’m working in the hive. It may just be that the music and the breath control keep me calmer, and so they feel calmer—but I like to think they respond differently to different kinds of music.

L.L.: Do you get to take bee vacations? Or is having bees like having a pet cat you need to find a sitter for when you go away?

Sara: You can definitely take bee vacations! If I were going to be gone for 2-3 months during the summer, though, I would probably give over control of my hives to another beekeeper for the season, and let them take the harvest for that year. But leaving for a week or two isn’t a problem, and in fact bees mostly like to be left alone to do their business.

L.L.: If you had to do it over again, would you still keep bees? How about poetry? What if you were at the beginning of your writing life again? Would you do that, too? (This is your chance to choose a whole new life with alternate creative and personal pursuits. Are you on board to go the same direction you already went? If so, why?)

Sara: This is a rich and complicated question for me. I started off as a young woman intending to be a concert pianist: all my early creative energy was poured into music and the rigors of classical training. When I left that world, transferring from a conservatory to a liberal arts college, my creative juice went into poetry, and I studied and wrote and published while I was in college.

Then there was grad school, and marriage, and children, though, and pretty soon I had nothing left over at the end of the day. In a sense my children became my creative work, and poetry seemed like a too-precious distant extravagance in comparison. I stopped writing, for almost 20 years.

But then I was diagnosed with cancer, and late at night when I was swimming in medicinal cocktails, I found I really had to write. My whole feeling about my life and my world was changing, and I had to write to make sense of it all. So this means that really I’ve only been writing & publishing poetry seriously for about 6 years.

All of this is to say that life is complicated. The twists and turns, music/ kids/ beekeeping/ marriage/ cancer/ poetry…well, I certainly have some regrets, and only an unthinking person would refuse to change a thing. But I am delighted with life now. It’s hard to look back and say I wouldn’t have made any of the choices that eventually led me to this desk in my little house. There are lots of ways to be creative and happy in the world: I think the choices I made were just one set of choose-your-own-adventure possibilities leading to this particular moment.

L.L.: Anything else you really want to say to us about either beekeeping or poetry?

Sara: I think the through-line between beekeeping and poetry is attention. When we study the worlds within our world, we discover beautiful intricacies, patterns, metaphors for our own existence, and boggling strangenesses.

That’s where poetry lives, in the weird mix of the familiar and the new.

Beekeeping has done this for me, for years, because it is in a sense multi-valent: it taps into sensory experience, memory, intellectual reasoning, social structures, climate breakdown & world-change realities, and scientific systems (I’ve probably left some things out).

But if I Ieft beekeeping, I would give something else that attention, and poetry would live in that new world for a while. Bees work well, but I think anything you give your full self to, your full attention, is poetry.

Photo by Chinh Le Duc, via Unsplash. Interview by L.L. Barkat.

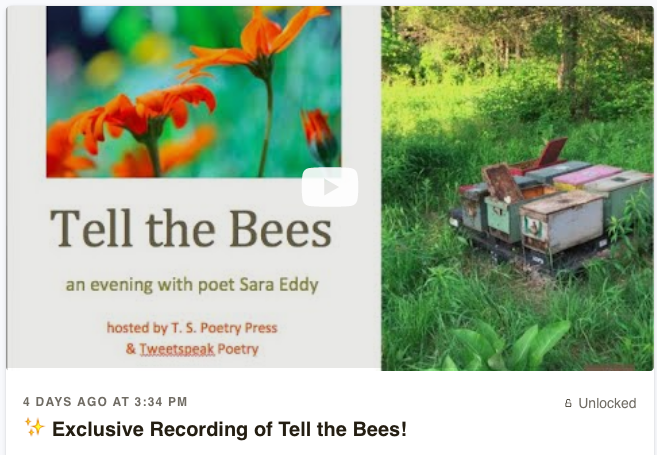

Get a Video of the Live Event

L.L. Barkat and Sara Eddy spoke together in a live event on August 5, with over thirty people in attendance.

If you’d like to hear the intriguing and fun conversation—along with an inspiring reading of the full Tell the Bees chapbook and video footage of Sara’s garden—join us as a patron to access the exclusive event video.

Enjoy an Audio Sample from the Video

- Found in Translation: Gently May It Sing - September 15, 2025

- Learning by Poetry: Vous venez d’où? - September 1, 2025

- 5 Fun Ways to Play with Language! - August 18, 2025

Bethany R. says

I’m thinking about Sara’s words here. “I think the through-line between beekeeping and poetry is attention. When we study the worlds within our world, we discover beautiful intricacies, patterns, metaphors for our own existence, and boggling strangenesses. That’s where poetry lives, in the weird mix of the familiar and the new.”

Thanks for sharing this interview with Sara Eddy!

L.L. Barkat says

That was one of my favorite sections of the interview, too, Bethany. (Of course, yes! The title even drew from it. 🙂 )

It was fun to come up with questions that would extend and interact with the live event we did. I loved the way Sara answered here and brought us new insights.