Poet Sara Eddy talks to bees. And she talks about food.

I will admit having talked with family pets over the years as if they were human. I’ve even projected conversations into their mouths. When my children were young, I wrote hand-illustrated stories about their pets. Judging by what I’ve seen in books and social media, I am not alone.

When it comes to food, I’m more utilitarian; some might say cretinous. I don’t get excited into flights of rhetorical fancy over food, with one possible exception: Blue Bell Homemade Vanilla Ice Cream. It’s the Texas-based company’s most popular flavor—and with good reason. They should market it as “heaven on earth.” Blue Bell ice cream is not sold in St. Louis, but I have a friend who makes runs to Rolla, Missouri, where it is sold, just to buy the ice cream.

Poet Sara Eddy is a beekeeper. She talks with her bees. She projects conversations and thoughts into the mouths and minds of her bees. And judging by her poetry, Eddy also enjoys food—peach, jam, truffles, honeycake, oysters, cantaloupe, dumplings, muffins, raspberries, donuts, olives, and burritos, to cite a few.

But in her hands, bees and food are something more than topics for humorous stories or tributes to favorite things to eat. They are metaphors for life and its experiences, and she writes about both bees and food in ways both original and profound.

Sara Eddy

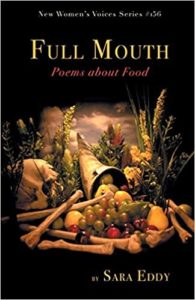

Eddy has published two chapbooks, or short collections, Tell the Bees (2019) and Full Mouth (2020). Published by Writing Maps, Tell the Bees is a short collection of eight poems, published as a type of pamphlet with color photographs of her own beehives. Full Mouth, part of the New Women’s Voices Series of Finishing Line Press, includes 30 poems, published in a more traditional short book format.

The eight poems about bees might be less about talking to bees and more about what the bees have to tell us. In early spring, Eddy opens a hive to hear, she hopes, the familiar buzz of awakening. Instead, she finds a frozen mass of dead bees. She buys new ones to take home, listening to their buzz as she drives and telling them what to expect. She lives through illness and chemotherapy while friends care, or try to care, for her hives. She describes the language of beekeeping, and she hears from a friend who’s considering keeping hives. And she figuratively steps into a hive as winter closes in.

Winter Queen

Fall flowers close up shop,

and no more pollen

constellates their legs,

driving their days with need.

The queen stops laying,

stops hunting back and forth

across the comb. She has felt

the cold nights and she begins

to lay only those eggs

that will become winter bees,

workers who will outlive the snow,

gather tight around their mother,

and vibrate with insect love,

kinetic warmth just for her.

They will be the last of their season;

no more will be born for months.

And finally the queen rests,

she lets it all go as it will,

she delegates persistence.

Every mother dreams of this

abdication, this pretend rest

during every solo drive to the grocery,

wheel-gripping, sleep-deprived,

feeling for a moment not regally

responsible, but simply empty.

And there’s the metaphor: Eddy identifies with that winter queen as a mother, around which the life of the family revolves. And the rest of winter for the bee queen is akin to the “pretend rest” of the mother who slips away for even a few moments to drive to the grocery.

Full Mouth employs food as metaphor. “Peach Jam” tells a story of attempt, failure, and starting over. “Oranges” is about what we take for granted. “Prep Work,” a poem about peeling potatoes and shrimp, becomes a memory of Eddy’s mother. “Honeycake” is a story about her son. “Dickinson’s Burrito” combines a hike, a burrito, Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, and the death of a young relative into a coherent meditation on life.

And preparing a chicken for a meal becomes a hymn of solidarity with poultry farmers, the people who raise the animals, and the people who prepare the food.

Butterflied

have I dismantled with my

bare hands, breaking

their brittle bones

to butterfly their wings

and legs, a violation

of species and physiognomy?

I rub the breast with garlic

salt, pepper, rosemary,

research again how hot the grill,

then I lay it down to rest

on a bed of iron and oil—

and I think of poultry farmers

and feathers, the twist

of the neck, a final screech

and a bright yellow

eye meeting mine

in anger and sorority.

In addition to her two chapbooks, Eddy’s poems have been published in numerous literary journals, including Threepenny Review, Poetica Review, and Abstract Mag. She currently serves as the assistant director of the Jacobson Center for Writing, Teaching, and Learning at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. Eddy received an N.A. degree in English from Connecticut College and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in American Literature from Tufts University. She lives with her family in Amherst, Mass.

Eddy is not simply a poetic voice but an original poetic voice. She learns from her bees and meditates upon what she’s learned. She understands that food is more than what physically sustains us and eating is more than an age-old ritual. Using simple, straightforward language, she tells her stories and ours.

Photo by Mark Chinnick, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

Lol, Glynn. You featured the one poem from Full Mouth that I actually decided not to read. (You know, vegetarian me. I just, somehow, couldn’t. 🙂 )

I agree with you that Sara has an original voice. It was that, and the sustaining element you mention, that drew me to her work—and became the impetus for sharing her poetry more widely (thanks for the review!).

Bethany Rohde says

Thanks for this, Glynn. I love the “Winter Queen” poem. (Sure is relatable at the end there.) And yes, she knows how to handle a poem. Clear voice and deft use of language. I bought her “Tell the Bees” collection last week and found each poem speaks with clarity while using vivid imagery.