Robert Selby tells the stories being forgotten

Something more than physical happens as you age. You become more conscious of art, history, and family. You might discover the joys, and hardships, of family genealogy, and the story that your great-grandmother Leona was said to have killed a man but got away with it. Or that a great-great-great-great-uncle fought alongside Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans. As you age, you love hearing and telling these stories, and you realize that family stories have to be told because they make sense of who you are and who your children are.

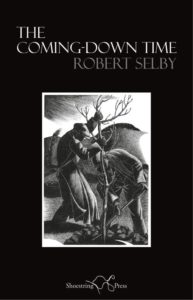

Robert Selby is still a relatively young man, but he seems to have grasped this imperative of family stories. His poetry collection The Coming-Down Time, published in 2020, is filled with the kinds of stories that shape and resonate through families. The stories are both large, like those of war, and small, like the commute to and from work that ends with a joyful sense of freedom.

Selby divides the collection into three parts. “East of Ipswich” contains 20 poems largely about the Great War (1914-1918). “Shadows on the Barley” are more contemporary and perhaps personal poems, but with a sprinkling of war influences as well. “Chevening,” 12 linked poems bearing only roman numerals for titles, returns to war-related themes (Chevening is the name of the official residence of the British Foreign Secretary in Kent).

The poems in all three sections tell almost ballad-like stories. You sense the stories are personal, even if separated by a century or more from the Great War. These seem like family stories, passed down through generations — stories of soldiers walking through the destroyed villages of Flanders, the young men who go to war and don’t return, the regimental photograph. Aside from war, Selby writes of a funeral service; three moons of the planet Jupiter; a Land Girls story during the war; a visit to Brunswick, Maine; and a daily commute by train entitled “Shadows on the Barley.”

Shadows on the Barley

sending all the bridge bats aquiver

into the pink evening;

when the people’s shadow on the barley

is not wanting for company

and the castle turret is gleaming,

it’s time for that part of the day,

a few hours at least, that we can say

are ours. The train slows down

into the freedom beyond the tunnel,

into the redbrick commuter town

where we can peel off our office flannel,

excited like kids home from school,

flinging windows wide, excitable

for the kettle’s click, the shower,

for the can’s nozzle in every flower,

then you, in your PJs already,

post-shower bob a glorious melee,

feet up on the kitchen table reading

the paper you didn’t get to

on the morning train because, again,

we had slumped together in sleep,

in a jerking, dribbling heap,

dreaming of shadows on the barley.

Robert Selby

Selby received a doctorate from Royal Holloway, University of London, for his study on the life and work of the Scottish poet Mick Imlah, who died in 2009 at age 52. He’s co-edited a collection of Imlah’s poetry. His poems have been published in The Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian, New Statesman, Oxford Poetry, and other publications. He works as a freelance writer and serves as editor of the poetry journal Wild Court. Selby lives in Kent in England.

Selby’s poems are plainly written to the eye and plainly spoken to the heart. And they go directly to the heart. You can imagine sitting near a fireplace with other family members while someone — a grandfather, perhaps — tells stories of the war, stories about family members and family friends, those who didn’t survive and those who did. And those who did survive have a special responsibility: to pass down the stories so that no one is forgotten.

Related:

Robert Selby reads three of his poems

Photo by Bernard Spragg, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

Katie Spivey Brewster says

“And those who did survive have a special responsibility: to pass down the stories so that no one is forgotten.”

Yes, Glynn. Thank you for sharing poets who do this well.

This is a post I will share with a good friend and a cousin who both appreciate art, history, and poetry.

Gratefully,

Katie

Glynn says

Thanks for commenting, Katie!