Poet Taras Shevchenko is the soul of a country

You read the newspaper and watch the television and social media reports, and you wonder how a tragedy like the Russian invasion of Ukraine could happen. You learn of atrocities and possible war crimes, and you say, “This is the 21st century?” Well, yes, it is. You might ask, “How does this happen?” In the case of Russia and Ukraine, the poet Taras Shevchenko might have an answer.

Shevchencko (1814-1861) was born in a village near Kyiv in Ukraine. Given his later literary fame, it’s surprising to learn he was born to a family of serfs. The region had been under the control of the kingdom of Poland, but various dismemberments of Poland had eventually led to control of Ukrainian territory by Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Russia controlled the area where Shevchenko was born, but it was a relatively recent control.

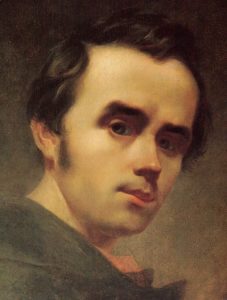

Young Taras Shevchenko

Ukrainians considered themselves Slavic but a distinct nationality. They remembered glorious times in the 17th and 18th centuries, times when they had their own rulers. But those times would return only 130 years after Shevchenko’s death. Ukraine would be ruled by Russia until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Shevchenko was a gifted artist, but no one knew that until he was required to be a servant of a local landowner’s son. The son traveled widely, and his servant accompanied him to Warsaw and St. Petersburg. He was given art lessons when his master discovered the young man’s talent. Artists and academics were so impressed that they eventually arranged to purchase his freedom (much to his master’s chagrin). At 24, Shevchenko was a free man for the first time.

In addition to his art, he’d begun to write poems, historical ballads and stirring epics about Ukraine’s history, collected in 2020 in The Poet of Ukraine.

It was his poetry that got him into trouble; when published, it quickly sold out, in both Russia and Ukraine. The poet was associated with a group forming the Society of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Kyiv, about which there was nothing particularly dangerous except its existence. This was the time of Tsar Nicolas I, whose government dealt speedily with conspiracies both real and imagined.

Shevchenko was arrested in Kyiv, sent to St. Peterburg for trial, found guilty, “exiled” to the Russian army and forbidden to draw or write. Part of his crime apparently was uncharitable descriptions of the Russian imperial family. He continued to write poetry in secret and with sympathetic commanding officers looking the other way. His previously published poems were already passing into legend in Ukraine. (In the following poem, note that “Kozak” is how we would spell “Cossack.”)

Dumka

But never leaves it.

A young Kozak seeks his fortune,

Seeks, but does not find it.

He has gone where chance has beckoned,

Where the sea is playing,

But his thoughts arouse him:

“Where have you not gone, a stranger?

To what hands entrusting

Father and your aged mother

And your smiling sweetheart?

People there are not your family,

Life with them is very hard.

With them you cannot weep,

Cannot freely talk.”

Far from home the Kozak’s sitting,

While the sea is playing,

Thinking, he will find good fortune,

But he meets with sorrow.

And the cranes hie homeward swiftly

In their ordered row.

Weeps the Kozak, — on life’s pathway

Piercing thorns have grown.

He would spend years in the military, a life he hated. He was finally released in 1857 but remained under police supervision. He was only 43, but he’d prematurely aged, and his health had suffered. He continued to write and support Ukrainian causes. When he died in 1861, shortly before Alexander II freed the serfs, the outpouring of grief in Ukraine was staggering, with an enormous funeral in St. Petersburg, where he’d been living. Eventually permission was granted to have his body reburied in Kyiv, and huge throngs greeted the train at every station and in Kyiv. He was buried near the Dnieper River; later, the land was bought and became a memorial to the poet.

As a poet, he was strongly influenced early on by the Romanticism of the early 19th century. His poems about love, relationships, and family seem to stand for his beliefs about Ukraine, and both its soul and its subjugation. “The Kobzar” is a group of eight ballads told by bards. “The Haydamaki” is the longest of Shevchenko’s poems, describing a revolt against the Poles in 1768. “The Dream,” written about 1843, reflects his growing antagonism to Russia. “The Grave” describes the faults in Ukrainian history and national character. Other poems were celebrations of individuals and historical stories. One, “The Testament,” is considered the most famous of his poems and a clarion call for Ukrainian freedom.

The Testament

Taras Shevchenko about 1859

When I die, O lay my body

In a lofty tomb

Out upon the steppes unbounded

In my own dear Ukraine;

So that I can see before me

The wide stretching meadows

And Dnipro, its banks so lofty,

And can hear its roaring,

As it carries far from Ukraine

Unto the blue sea

All of foeman’s blood—and then

I will leave the meadows

And the hills and fly away

Unto God Himself.

For a prayer…But till that moment

I will know no God.

Bury me and then rise boldly,

Break in twain your fetters

And with the foul blood of foemen

Sprinkle well your freedom,

And of me in your great family,

When it’s freed and new,

Do not fail to make a mention

With a soft, kind word.

Shevchenko, as one biographer has noted, “had been a serf for 24 years, a free man for nine, a Russian soldier for ten, and under police supervision for four.” And yet he gave his people something precious and priceless — a celebration of their history and a hope for their future. And for that, he’s deservedly known as “the poet of Ukraine.”

Photo by Nicklas Lundqvist, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Laura Lynn Brown says

Oh, what a timely post. Thanks, Glynn, for introducing us to this poet, and giving us two of his poems.

L.L. Barkat says

I appreciated this post so much, too, Glynn.

For every struggle, there is more history than we know.

(Beautiful poems.)

Sandra Heska King says

Wow! Thank you for this. I wonder what he would write today.

Bethany R. says

Thank you for sharing this with us.