Jesse LoVasco Tells a Story of Native Americans

It wasn’t planned. I was reading a book about the Constitution and the American Founders. It included two chapters on Andrew Jackson and how popular sentiment ran counter to the principles underlying the Constitution. The example cited was Jackson’s determination to remove the five native American tribes collectively known as the Cherokees from their ancestral lands, primarily in Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee. The removal, which began in the early 1830s, was ultimately carried out by Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, in 1838. Thousands of people died on the “Trail of Tears” to forcible resettlement in Oklahoma.

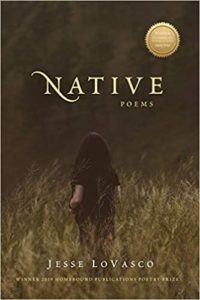

From that book, I turned to Native: Poems by Jesse LoVasco. It wasn’t intentional on my part; it was the simply the next book to read. Without a single reference to the Cherokee tribes or the Trail of Tears, many of the poems included in the collection told that story. I read the first few poems and began to hear the theme music from The Twilight Zone playing in my head.

Jesse LoVasco

Although each poem is a separate entity, LoVasco is telling a story, a story of Native Americans then and now. She is the first immigrant. She drives through the territory of Akwasasne (also spelled Akwesasne), which straddles parts of New York State, Quebec, and Ontario. She meets a Dakota woman at a flea market. She searches for keepers of medicine. She listens to a native woman speak to a crowd gathered in the streets of Detroit. She sees the sky perform a rain dance. She looks for her own tribe and finds women in a circle, singing a ritual song.

While all of these may be but remnants of a once dominant culture, the fact is that they remain. They’re still there, often in mute witness but witness nonetheless, witness to the eternal and a reminder of what’s temporal. We don’t understand, as she writes in “Hollow Reed,” that “Earth will survive. / It is us, / who will cease to exist.”

But perhaps we do understand, if we take the time to consider it. As much as they are about Native Americans, these poems resonate even for those of us (this reader included) without a drop of Native American blood. Our technologies (like books and computers) may have “stopped the spirit of a story / from moving from / one generation to the next,” as she says in “The Spirit of a Story,” but we understand the power of a good story. And Native is filled with these stories.

Watershed

raised to speak

our native voice,

we dispersed to places

on the earth, to get

a sense of our sound,

close, but far away.

if you trace your finger,

follow lines

along waterways and winding roads,

you will find each of us,

nestled in

the same watershed,

veins of the

mother that breathed

our own

mother into life,

each like a note on

a sheet of music,

flowing like rivers, moving

toward the humming of the sea.

—Jesse LoVasco

LoVasco studied poetry at Vermont College. Her poems have been published in a number of literary publications, including Written River, Imprinting Waves, and others. She is also a yearly contributor to PoemCity in Montpelier, Vermont.

Read the poems of Native and listen to the land, nature, the elders, and the wisdom of the past, a past that is always with us.

Photo by Steve Slater, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Boris Dralyuk and “My Hollywood” - September 9, 2025

Jesse LoVasco says

Dear Glynn,

I’m not sure when this post was written, but I just found it today. Thank you so much for the time and focus you took to explore the poems in Native. This compilation of poems transpired through a journey to time where many encounters and greater nature relationship and rituals gave meaning to my life work. It is fascinating to read your perspective. I put the work out into the world, and I’m not ever sure who will resonate with it. Thank you very much.