Form Poetry for Children? It’s Also for You 🙂

Poems can be like hangry little children. They may need a little form to perk them up.

My earliest introduction to poetry was through form, in elementary school. Our language arts classes put together a book of form poems called Pegasus, after the mythical white winged horse who is the symbol for poetry. We wrote short forms, like tanka, senryu, and diamante, forms I still turn to when my poems get fussy.

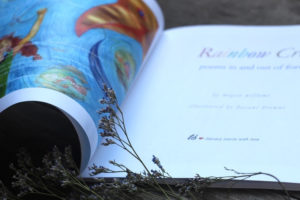

Rainbow Crow, my picture book of poems for children, owes its existence to my friend Sally Clark, who wrote an ongoing series of form poems for a homeschool publisher. Each month Sally composed thirty form poems, and each month she brought them to our writers’ group for feedback. I felt like I was back in elementary school again — in the best way.

As Sally wrote about ants and pumpkins and dragons (oh my!), I wrote about crows. It had not been long since a crow stole my son’s pair of glasses, kicking off an obsession with these bad birds. Some of those poems I wrote fifteen years ago are in Rainbow Crow, including “Resume,” “Definitions,” “Tools,” “Ginger,” “Blinded,” “Love Birds,” “Q&A with Crow,” and “Ventriloquist.”

But I wasn’t done with form poetry or with crows.

When Tania Runyan’s How to Write a Form Poem released, I tried forms that were new to me, like the ghazal , the acrostic, and the catalog poem. These forms helped shore up some of my poems that were stashed away, awaiting better structure.

Think of form as a fence — it has boundaries that show the writer and reader where to go. Free verse is free range — no fences, no rules. Ironically, free verse can be much harder to write well. A fence can provide structured space for creativity to root and bloom.

It’s usually best to start a form poem by following the guidelines, and then decide if those help the poem or hold it back. Consider writing two poems — one following the form and another tweaking it.

Form Poetry for Children to Jumpstart You!

The next few posts will explain four of the forms used in Rainbow Crow, so you can try them too. Here at Tweetspeak, we love to play with form poems, whether it’s something familiar, like haiku, or something less well known, like an As In poem.

Try It—Start With Free Writing

Before we begin feeding our poems with form, sharpen your pencil and put on your thinking cap.

1. Think of one subject that interests you, one you would enjoy approaching in multiple poetic ways. Try free writing about it, to begin. The free writing needn’t be in poetic form. Share your free writing with us in the comment box today.

2. Get ready to write poems on your subject using all four forms we’ll explore together: clerihew, diamante, rondelet, and senryu. Be grateful I’m not asking you to write thirty forms!

3. Read up on a few other forms. Does your subject lend itself to an ode? A sestina? A pantoum? A villanelle? Different forms of poetry are good for different things. For example, a sonnet is often best for a love poem.

4. Save this question for later: What have you learned about your subject by writing about it in a variety of forms? In a future post I’ll discuss what I’ve learned from writing dozens of forms of crow poems and invite you to learn something too.

Photo by jimpg2_2015, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Megan Willome.

Browse more children’s poetry

“Megan Willome has captured the essence of crow in this delightful children’s collection. Not only do the poems introduce the reader to the unusual habits and nature of this bird, but also different forms of poetry as well.”

—Michelle Ortega, poet and children’s speech pathologist

- Perspective: The Two, The Only: Calvin and Hobbes - December 16, 2022

- Children’s Book Club: A Very Haunted Christmas - December 9, 2022

- By Heart: ‘The night is darkening round me’ by Emily Brontë - December 2, 2022

Leave a Reply