Douglas-Fairhurst Brings a World, and a Man, to Full Life

Charles Dickens finished the serialization of his autobiographical novel David Copperfield in 1850. More than a year would pass before he began the monthly installments for Bleak House in March of 1852. The intervening time wasn’t a gap or rest year. “Rest” is not usually a word one associates with the British author.

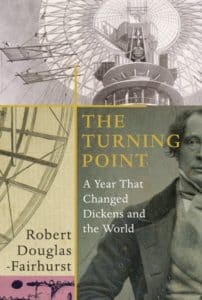

But it was certainly more than time off between novels. In fact, argues Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in The Turning Point: A Year That Changed Dickens and the World, that year marked a change in Dickens’ writing, which took a darker turn with Bleak House. It was the year of Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition, with the famous Crystal Palace in Hyde Park containing wonders and technology from the world over. Dickens himself was becoming more involved in social causes and projects, like preparing Urania Cottage to provide a haven for prostitutes to leave that life behind. At the same time, his lease on #1 Devonshire Terrace near Regents Park was ending, and he had to find a new place for his large and growing family to live. It was also a year of personal tragedy for Dickens, with the death of his young daughter and his father.

Douglas-Fairhurst received his Ph.D. from Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 1998. He is a tutorial fellow and senior dean of Arts at Magdalen College, Oxford, where his teaching focuses on Romantic, Victorian, and Modern literature. His books include The Story of Alice, Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist, and Victorian Afterlives. He’s published extensively on the subject of 19th century literature.

He knows Dickens, and knows him well, and not only Dickens the writer, but Dickens the man. And Douglas-Fairbanks presents Dickens the man in his time and his element—feverishly editing his weekly magazine Household Words, staging amateur theatricals for his family, sitting at his father’s bedside as the man dies a very painful death, taking his famous (and lengthy) walks about London, and casting a somewhat suspicious eye to the great edifice rising in Hyde Park and all that it represented.

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Those walks were important, even the relatively short ones like his two-mile walk from Devonshire Terrace to the offices of Household Words on Wellington Street in Covent Garden. Dickens was known as a fast walker, but he was also a deeply and profoundly observant one, a sponge for sights, sounds, smells, and especially people he encountered along the way. Everything was grist for the literary mill that was Dickens.

The event of the year was the Great Exhibition, part trade fair and part “an old-fashioned cabinet of curiosities,” as Douglas-Fairhurst describes it. The Crystal Palace contained marvels from a steam-powered envelope-making machine and toilets that flushed with a pull-chain to a collapsible piano and diamonds the size of birds’ eggs. Authorities were also concerned that the exhibition might present a target to revolutionaries; the European unrest of 1848 was still fresh in the minds of many. But nothing unexpected happened, and the event was a huge financial success. It earned enough money for the purchase of an extensive tract of land where the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Museum of Science and Industry, and the Natural History Museum would be built.

Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition

Dickens had reservations about the exhibition, reflecting his reservations about technology in general. But for the author, as well as many others, the real attraction of the Great Exhibition was the people visiting the Crystal Palace, from the toffs of Rotten Row to the working-class people who arrived on special trains from other parts of Britain. All of it would frame what would start in 1852—the serialization of his next great work, Bleak House.

The Turning Point is a marvelous story that Douglas-Fairhurst weaves. He writes as a readable academic, with an engaging style that brings his subject and the times alive. The book is also an impressive work of scholarship, adding depth to our own understanding of this greatest of British writers.

Related:

Where to Start with Charles Dickens, with Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst on Becoming Dickens

Photo by EVO GT, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

Leave a Reply