Step back a century with Cassell’s Shakespeare

It was an intriguing invitation. Read all the works of William Shakespeare in a year?

Poet Dave Malone posed the challenge. Writer Callie Feyen accepted. I wavered, trying to balance time commitments, and then I leaped. But before I told Malone yes, I checked to make sure my memory was correct that I indeed had a one-volume edition of all of Shakespeare’s plays. I do. I also have several copies of several individual plays, small, hardbound editions published between 1890 and 1930.

Also pushing my decision was having read The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 by James Shapiro, the movies Shakespeare in Love and Much Ado About Nothing, which I truly enjoyed, and having seen Vanessa Redgrave and James Earl Jones playing the leads in Much Ado About Nothing at the Old Vic Theatre in London in 2013.

My copy of the 1913 edition of Cassell’s Illustrated Shakespeare has been occupying space on my bookshelves for more than 30 years. Judging by the bookplate, I purchased the book sometime in the late 1980s from Dappled Gray Antiques, a shop in my St. Louis suburb of Kirkwood that had been across the street from the Kirkwood train station. The antiques are long gone, the owner having retired and moved away. The train station is still there, an Amtrak station operating in a building built in 1893.

I’d purchased the Shakespeare volume for something less than $15. It hearkened back to a time from the 19th well into the 20th century when middle-class families not only bought collections like this one, often published in handsome bound editions, but would read from them aloud.

Cassell’s was a London-based publishing form founded in 1848. John Cassell had been a carpenter, temperance advocate, and grocery merchant before turning his hand to publishing. He started with a weekly newspaper and expanded to include other publications. But all did not end well; he declared bankruptcy in 1855 and accepted a junior position in the reorganized company. Better business management followed, and the firm flourished. One of its notable successes was publishing a previously unknown writer named Robert Louis Stevenson.

Drawing of Falstaff, Henry IV, Part 2

Cassell’s serialized the works of Shakespeare as individual plays (much like Charles Dickens serialized his novels). In 1886, the firm issued a collected edition, Cassell’s Illustrated Shakespeare, annotated by Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke and drawings by H.C. Selous. Some 17 editions were published over the years, many in three-volume sets. The one-volume 1913 edition, which I have, uses both drawings and photographs. It also includes an introduction by Frederick James Furnival (1825-1910), a philologist and one of the founders of the Oxford English Dictionary, and John James Munro (1883-1956), a noted Shakespeare scholar.

Reading the Cassell’s Shakespeare is not unlike reading the King James Version of the Bible. The language is, of course, similar, given that Shakespeare was writing before, during, and after the KJV translation was made. The plays are printed in two columns on a page, which, over some 1,094 pages, can sometimes make for tedious reading. The drawings are wonderful; the photographs of various scenes in plays from the period look like stills from old silent movies. My volume even had tabbed sections for each play and the poetry, like a bible.

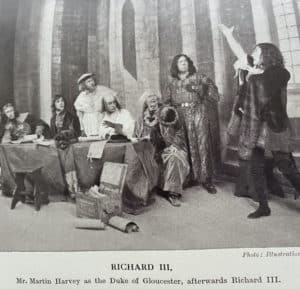

A stage play of Richard III

Our Shakespeare reading group started with Twelfth Night (appropriately during the Christmas season). We’ve traveled through histories, tragedies, comedies, long poems, and the sonnets. Most recently, we’ve read Macbeth, which I believe is my favorite of all of Shakespeare’s plays, and we’ve just started Troilus and Cressida. Based on our comments and reactions, the play liked the least by our group so far has been The Taming of the Shrew. Overall, I’m more a fan of the histories and tragedies than the comedies, which seem to recycle similar narrative devices—disguises, twins, shipwrecks on islands, and assumed identities.

To read Shakespeare like this is to immerse yourself in language and lines that have become almost integral to our cultural heritage. The play’s the thing! All the world’s a stage! You become fully aware of the degree to which Shakespeare has shaped our culture and indeed all of us who inhabit that culture.

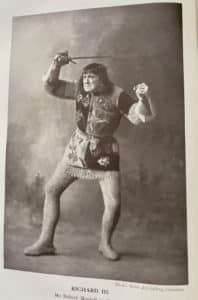

Actor Robert Mantell playing Richard III

Cassell’s went the way of many publishing firms. It was acquired by Crowell Collier & Macmillan in 1969 and sold it to CBS in 1982. CBS in turn sold it in 1986. Sold again to the Orion Publishing Group in 1998, it was eventually merged to become part of Weidenfeld & Nicholson. “Cassell Illustrated” survives today as an imprint of its publisher. (A history of the company was published in 1922 and is available free online.)

My 1913 edition is listed on Amazon for a price of $902.81, which would be quite a markup from my original purchase price. I seriously doubt it’s worth that much, even in its good condition. But its contents are priceless and timeless, opening a door to both the time of Shakespeare and the time of its publication, when families might often be found reading Shakespeare to each other after dinner.

Photo by Theophilos Papadopoulos, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Maureen says

Enjoyed reading this, Glynn.

In college, I took a two-semester course in Shakespeare. We used a single volume, which I had until I moved his past year (fully annotated by me, it was part of 10 boxes of books I gave away), which had the tiniest type. I’ve seen the movies and attended performances of Shakespeare’s plays (in England, at Stratford, and at the Folger Shakespeare Theatre, in D.C., but did not return to the volume as reading material. I enjoyed the class a lot. Shakespeare wrote magical, funny, romantic, and deeply tragic works; he also wrote bloody plays (I mean that literally), and some truly not worth reading. The performances at Stratford, by the way, were terrible.

Glynn says

Maureen, I’m reading one of those “plays not worth reading” right now. I was forewarned many years ago by my high school speech teacher, who called reading it “an act of ‘trudgery'” – a combination of drudgery and trudging through the text.

L.L. Barkat says

Glynn, the “trudgery” comment made me laugh!

I really love the idea of families having read Shakespeare together—and, really, any classics at all. It was a kind of seamless education. No need to study for the SAT there. 😉