Natasha Tretheway Reminds

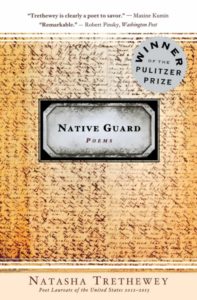

In her Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry collection Native Guard, Natasha Trethewey reminds us that history is complicated.

“Native Guard” refers to a military regiment and an event during the American Civil War. The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was a regiment of Black men who fought for the Union. The regiment was based in New Orleans and was composed of a few free men of color but mostly formerly enslaved men who escaped from area plantations. The regiment played a prominent role in the Battle of Port Hudson, a Confederate fort north of Baton Rouge then on the Mississippi River that bears the distinction of enduring the longest military siege of any town in North America. The town surrendered to Union forces a few days after the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863.

Many members of the guard fell in the front lines. The Union commander, General Nathaniel Banks, was petitioned by Confederate forces to bury them, because of the smell of the decomposing bodies. The Union commander, General Nathaniel Banks, declined the petition, saying he had no dead there. In other words, he rejected both the request and the idea that the Native Guard was part of his army.

Trethewey’s title poem is a series of 10 chronological poems about the guard, what it accomplished, and how it was disregarded by its own Union general (Banks had also been systematically removing any officers of color from the three regiments of Black men). She considers the general’s dismissal of the contribution these made to the battle.

From the title poem, “Native Guard”:

June 1863

as it is written on stone. Some will not.

Yesterday, word came of colored troops, dead

on the battlefield at Port Hudson; how

General Banks was heard to say I have

no dead there, and left them, unclaimed. Last night,

I dreamt their eyes still open — dim, clouded

as the eyes of fish washed ashore, yet fixed —

staring back at me. Still, more come today

eager to enlist. Their bodies –— haggard

faces, gaunt limbs — bring news of the mainland.

Starved, they suffer like our prisoners. Dying,

they plead for what we do not have to give.

Death makes equals of us all: a fair master.

In a later poem, “Elegy for the Native Guards,” Trethewey notes what happened to the remains of the men who fell in battle. Eventually, the Mississippi changed course and inundated the battlefield, leaving the fort itself high and dry. Years later, the Daughters of the Confederacy placed a plaque at the fort’s entrance, recognizing the names of the Confederate soldiers. No plaque exists for the Native Guard. Trethewey’s poems stand as that plaque.

Like many stories in American history, the story of the Native Guard is complicated. Two Native Guard regiments existed, one that fought for the Union and one for the Confederacy. Bearing the same name, the Confederate regiment comprised freemen organized by a group of Black leaders in New Orleans to support the Confederate war effort. It existed from 1861 to 1862; many of its members eventually joined the Union regiment.

Natasha Trethewey

Trethewey served two terms as U.S. poet laureate (2012-2014) while serving simultaneously as poet laureate of the state of Mississippi. She’s published a memoir, a book of nonfiction, and five collections of poetry; she’s also served as editor for three books. Her honors and recognitions include six fellowships, some nine poetry prizes, and election to the Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets. She currently reaches English in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern University.

The poems of Native Guard are about more than the Civil War. She writes about Southern Gothic; Southern history, including a “documentary history” of Mississippi; family; and more. All the poems reflect the poet’s piercing eye, an eye that probes beyond a surface understanding.

Growing up in Louisiana, in eighth grade I took the required course in Louisiana history. We spent several weeks on the Civil War. Neither the teacher nor the textbook mentioned the Native Guard; the book did note that the Battle of Port Hudson resulted in complete Union control of the Mississippi River. But, as Trethewey reminds us, history is about more than what’s in the textbooks.

And the story of the Native Guard is complicated: two regiments from the same region fighting on opposing sides, the Union regiment disregarded by its own commander. Trethewey’s poems recognize the men who volunteered, how they fought, how they fell, and how they were not remembered.

Photo by Joe van petten, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

How to Read a Poem uses images like the mouse, the hive, the switch (from the Billy Collins poem)—to guide readers into new ways of understanding poems. Anthology included.

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Megan Willome says

I read this book by Trethewey a few years ago, and it spoke of many things I was not familiar with. Recently I’ve been reading some history about my state (Texas) that includes details about our Black population that my school textbooks left out, even with required courses on the subject in grades 4 and 7.

Glynn says

The story of the Native Guard — both of them — surprised me, because I never read of either in Louisiana history. The Battle of Port Hudson was significant for a number of reasons — the last Confederate fort guarding the Mississippi River, the longest siege, and one of the first battles involving a regiment of Black troops. Part of the reason, I think, is that so much of Civil War history has focused on the eastern U.S. — Virginia, the Battle of Atlanta, Maryland, and Gettysburg.