Writer’s Note: It wasn’t Ramona or Henry or Beezus who gave me the idea that I might one day be a reader (and perhaps even a writer). It was Leigh Botts, who writes like himself, who listens to the pinging sound of the gas station at nights, who tells Mr. Henshaw that he’s never been told he’s gifted or talented, but he knows he’s not stupid. It is Leigh Botts for whom I’m forever grateful to children’s author Beverly Cleary, for giving a young girl — who wanted to write like herself, who loved listening to the sound of the El at night before she went to sleep, who never once was told she was gifted and talented but hoped she wasn’t stupid — a character and a story to hold on to.

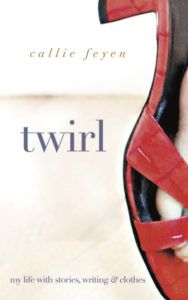

Beverly Cleary passed away on March 25 at the age of 104. This chapter from my second book, Twirl: My Life in Writing, Stories, and Clothes, is posted in honor of her.

Twirling

I once had the perfect dress. The top layer was gauzy and it was a charming brownish-beige. The lining was a cream crinoline. The dress had a pattern, probably flowers, though I didn’t care about the color or the design. This dress twirled, and that’s what I cared about. The gauze and the crinoline made a delightful swish sound when I moved and, if I spun, the material lifted effortlessly, almost parallel to the floor; the ends lightly brushed my palms if I held them out at my waist.

When I ran downstairs from my bedroom into the kitchen, the dress billowed out and I’d pretend I was Scarlett O’Hara running down a set of stairs at Tara to meet her many gentlemen callers. In the early evening when it was dark and too cold to play outside, my mom put on classical music while she made dinner and I’d leap and twirl in the living room and the dress frolicked with me. The dress had a matching blazer and I’d put that on, then I’d staple scraps of paper together at my dad’s desk with his olive green stapler. I was a corporate businesswoman in that dress. I was a ballerina. I was a Southern Belle. I was anything I dreamed up in that dress.

I must’ve been in 5th grade when the dress came to me in a big bag of hand-me-downs, and when I first held it I knew two things: I loved it, and I would never wear it in front of my friends, girls I’d known since I was 5.

When we were 5, we met at the corner of Jackson and Gunderson to walk to school together. There was a wire fence with purple morning glories weaving in and out of its ties. We spent half the day in kindergarten, then raced to the fence on the corner of Jackson and Gunderson and hoped the flowers were still awake. They were closed by noon, sleeping until the orange sun crept over Lake Michigan and the Sears Tower to wake them up again.

As we got older, we didn’t talk much about the morning glories, but we still stopped at the fence where they hung and chatted for a bit before walking towards home. I think I was in 3rd grade when the school gave us a test to determine whether we’d get into a class labeled “Academically Advanced.” We took it every September for the rest of our elementary school years. I never got in. My friends did, though. Soon, they could explain the scientific reason why morning glories closed their petals, and I walked the last bit home by myself, the “el” train’s rushing sound growing louder while I tried to understand flowers unfurling and blooming when the temperature is right.

During those years, my friends left our homeroom and went to the “AA” class. They were in book clubs, put on plays, and made posters of characters they read about in stories. I stayed behind and worked on dittos labeled “reinforcement.” The purple from the ink sometimes rubbed off and stained my fingers.

I loved the dress, but I worried that maybe it was frivolous and silly. Nobody I hung around with had a dress like this, and because I felt so wonderful in it, I kept the dress a secret because I didn’t want anyone to tell me it was something other than what I believed it was.

We lived next door to a library, and before I could read, I would go there and check out a stack of books so high that the librarians would encourage me to leave my roller skates with them so I could carry the books home. There was a little white house in the children’s section, and, inside, its walls were filled with picture books. I used to sit inside the house and page through stories until one of the librarians peeked inside and told me my mom called and it was time for dinner.

Once the letters began to make sense, and the September tests had begun, reading became a task. Reading meant drills and memorization and it didn’t mean looking at and wondering about pictures. I stopped visiting the white house because I figured I was too old for those books, but I could always see it, through the library glass, from my bedroom window.

I remember staring at the house from my window one afternoon. I was particularly annoyed and feeling left out by something I couldn’t understand and articulate. The windows were open and I could smell the air dancing throughout my house. It smelled green. I was sitting on my bed watching squirrels prance and leap along the telephone line and I was listening to the “el” cross into the city a mile away.

My dress was in the back of the closet, the last piece of clothing in the row. A big bag of Barbies and their clothes sat below it, also hidden. I kept them in the darkness of my closet so my friends wouldn’t see them when they came over.

That day, though, I was by myself, so I walked over to my closet, reached my arm way in the back and pulled my dress off its hanger. I lifted my Barbie bag off the floor, too, and tossed it on my bed.

There are few things in life I love more than pulling on a dress I absolutely adore. Sliding on jeans straight from the dryer? That’s nice, I’ll admit. I also like pulling on a white T-shirt that’s both crisp and soft, like the perfect chocolate chip cookie. Slipping on a dress, though, is transformative. Something powerful happened to me when I wore my twirl dress, because I felt beautiful: smart beautiful, funny beautiful, brave beautiful. Dresses have always helped me imagine myself differently. I knew this even at 11.

I plopped back on my bed and sat so that my dress splayed out perfectly in a circle while I played with my Barbies. What would I read if I was smart? I thought, as I braided one of my Barbie’s hair.

If I was smart, I thought, walking my Barbie around the perimeter of my dress, I would go outside of the little white house and pull a book to read, where the shelves were higher, the books were smaller but thicker, hundreds of pages of small words.

I made my Barbie do a perfect leap and land on my windowsill. I adjusted her so she stood by herself, looking out the window at the books, her hands and face on the glass. “Start with the A’s,” I swear I heard my Barbie whisper. “Wear your dress and start with the A’s,” she said.

I looked at my smiling Barbie looking at the books. I slipped my thumbs underneath my dress straps like I was wearing overalls and sat back on my bed to survey the situation. I was both excited and afraid of the story I was thinking of stepping into, but I got off my bed, did a twirl, and walked to the library. I would start with the A’s.

It’s easy to whip up stories sitting in your room alone with your toys and with your favorite dress on, but actually stepping into that new world you thought you were brave enough to explore is a different story. I marched into The Maze Branch Public Library and remembered with a pang that this time I would not go in the house to pick up a picture book. I also remember feeling heat reach my cheeks when I realized I was wearing my twirl dress in public. I don’t belong here, I thought. This dress is ridiculous and I’m not smart enough to read chapter books. I should go home.

“Hello, Miss Callie!” It was Mrs. Grinbard, the kindest, classiest librarian I’m certain the universe has known. She wore long skirts that swished slightly as she walked. Her nails were painted a rose pink and I admired them as she reached for books and pulled them from the shelves.

She walked in high heels, shoes I couldn’t wait to be old enough to wear. In fact, I remember worrying that high heels—specifically, patent red high heels—would be out of style by the time I reached an age appropriate enough to click and clack in them.

“How are you?” Mrs. Grinbard asked. She was standing behind a circulation desk, and I smiled and walked toward her.

“I’m fine, thank you,” I told her, and put my hand behind my back once I reached the counter. I was always fidgeting and wanted to be graceful like Mrs. Grinbard, so I held my hands behind my back to keep from fiddling with my fingers.

Mrs. Grinbard was sorting through a stack of library cards and matching them to the books that had been turned in. When she found the right card, she slid it into a machine that made a tremendously satisfying thump as it stamped the date on the card.

“Would you like to help?” she asked, slipping the card into its pocket inside the cover, then closing the book. I nodded immediately. I’d been helping Mrs. Grinbard since before I could read. My brother and I got to test out the educational toys the library received when we were toddlers and, as I grew, she always found things for me to help with. Sometimes she’d let me sit in the back room and we’d eat lunch together. I used to hope that when I grew up I would be a librarian and work with her. We’d be the fancy librarians and everyone would request our help because we had exquisite taste both in books and wardrobe.

She tilted her head to tell me to come around to the other side, and I did my best not to run. Instead, I walked calmly, and businesslike, as she did. I took long strides so my dress would swish like hers did and I was glad to be wearing it.

As I walked to where she stood, she pushed a step stool like she’d done so many times so I could reach the books. That day, though, she stopped and put a heel on the stool, and I stopped walking towards her when I heard the thunk of her heel.

She pulled her glasses to the bridge of her nose and surveyed me, a smile on her face.

“Look at you,” she said. “I bet you don’t need this anymore.” She pushed the stool aside with her foot. I smiled and walked to stand beside her, feeling grown up and remembering the power of my dress. We worked together, opening the covers of stories and sliding their cards to check them in for someone else to enjoy. I loved listening to the crinkle of a cover as I opened it and I loved the feel of cardstock sturdy in my hands. I felt good standing next to Mrs. Grinbard and working without a stool.

“I came here to check out some books,” I told her, as I put a card in the slot of the date stamp machine.

“Anything in particular?” she asked, and I told her I was going to start with the A’s outside of the white house. She nodded and I wondered if she thought that was a good plan. How did she go about picking out a book? Did she keep lists of titles in her purse or in a journal? Did she wander around the library after it closed and take home the books that were left on tables? Did she always love to read? Was she always good at it?

“I always like Beezus and Ramona stories,” she said, as she lifted a stack of books and put it on a cart to be shelved. “That’s Beverly Cleary.” Mrs. Grinbard took my finished stack and placed them on the cart. “She’s pretty close to A.”

I nodded and watched her roll the cart to the side of the circulation desk. Those stories would soon be in the hands of the shelvers, the high school kids who’d come after school and carry the books to the bookshelves. Sometimes I’d watch the high schoolers in the library, watch them stop shelving and stand behind a carrel and sneak a few pages of the book they were supposed to shelve. Sometimes the book would never be shelved and, instead, the teenager would put it next to her purse or backpack to be checked out when her shift ended.

There was nothing cooler than a teenager. Everything they did was cool, even turning pages of a book. I wondered what I’d be like when I was that age. Would I be smart then? Would I like to read? Why didn’t I like to read now? I fiddled with the hem of my dress as I wondered and Mrs. Grinbard put a hand on my back, gently coaxing me out of my reverie.

“Come find me when you’ve found a story,” she said. “I’ll let you check it out by yourself.”

I walked towards the little white house; a twinge of sadness that I wouldn’t go in pulled inside my stomach. I walked to the A’s.

There were lots of titles having to do with wolves or dogs or bears. I wasn’t a fan of animals unless they were in cages, so I passed over those. I pulled a few books from the shelves and looked at their covers. So many pictures made it look like the main character was on some wild adventure—over the mountains, into the woods, out to space, or plopped into a fairy kingdom. I don’t know why, but I wasn’t interested in those kinds of adventures. I liked thinking about what was going on in front of me: walks home from school, hoping the purple morning glories that were so bright on the grey fence hadn’t fallen asleep yet; wearing my twirl dress and playing with Barbies in secret; Mrs. Grinbard; the little white house. Maybe I wanted a story where things happened slowly, no one was whisked away, and change occurred through repetition, in returning to a place again and again.

I put a few books on the table next to me and shelved the rest. We weren’t supposed to do that, but Mrs. Grinbard showed me how to do it one summer afternoon when I walked through the library’s doors and told her I knew all my letters.

“And do you now, my darling?” she asked and walked around from her desk to greet me and hold my hand. We walked together up the three steps that led us to the children’s section. She picked up a few picture books left on chairs and tables and pointed to a white sticker on the spine.

“These are the three letters in the author’s last name,” she said and tapped the sticker. I loved the sound her finger made on the book as she pointed to the letters.

She led me to the shelves and showed me how to work through the letters to put them in their proper place. “You can’t just shove all the S’s together,” she said.

I loved the organization in it. I loved thinking through the order of BET and BRE. If the author wrote more than one book, as Beverly Cleary had, I would have to think through the titles alphabetically. It felt like a game, running my fingers along their spines watching order take shape. That’s how I found Dear Mr. Henshaw:

Dear Mr. Henshaw,

My teacher read your book about the dog to our class. It was funny. We licked it.

Your freind,

Leigh Botts (boy)

Any writer knows first sentences are important, and these few proved to be magic. I laughed out loud at Leigh’s spelling mistake and imagined a class full of kids licking a book (I didn’t pick up that friend was spelled wrong), I was intrigued that the main character was a boy (there was something excitingly mysterious about boys), and I loved that this was a book of letters. That was my favorite sort of book.

Books of letters felt like correspondence that was meant for someone else’s eyes. Inside the little white house, I always picked up The Jolly Postman because it, too, was a book of letters—greetings and invitations that were meant for somebody else—and I slipped them from their envelopes and read them like a thief, wondering what it would be like to crash a royal ball.

I knew that these characters and their stories were made up, but they wrote letters to each other, and though it was just a device used by the authors, this felt real enough for me. Now I had to know more about Mr. Henshaw and Leigh Botts. So I turned the page.

I have no memory of when I read Dear Mr. Henshaw. I can’t remember if I checked it out, walked home, and shut the door to my bedroom and read until it was dinnertime. I don’t know if I brought Cleary’s story back to the library on time. I don’t know if I slipped it into my book bag and pulled it out during school when I was finished with my work. I doubt that ever happened. I was never finished with my work.

What I do remember is how to spell friend from reading the book. “My teacher taught me a trick about friend,” Leigh writes. “The i goes before the e so that at the end it will spell, end.” I remember thinking, how clever, and also, how sad that friend has the word end in it. I thought a while about the spelling of friend and of endings and the girls I’d known since I was 5. We all sat crisscross applesauce and looked at shapes until they formed letters and letters formed words. We all aha-ed when we sounded out cat and book, and we ran to the morning glory fence to see if the flowers were still awake.

Leigh signed one of his letters, “De Liver, De Letter, De Sooner, De Better, De Later, De Letter, De Madder, I Getter.” My cousin Tara and I were pen pals and I began signing my letters to her this way. I remember these sentences: “This school doesn’t say I am gifted and talented, and I don’t like soccer very much the way everybody at this school is supposed to. I am not stupid, either.” Those words felt good to try on, just like my twirl dress.

By 6th grade, my twirl dress was too small. If I stepped into it and pulled it up, the waist got stuck on the width of my hips. If I gave it a tug, I could pull it on, but the zipper couldn’t close no matter how much I sucked in my breath. Eventually, it got put in a Goodwill bag, hopefully a gift for another girl.

I began my 6th grade school year without my dress and with one more chance to get into the “AA” class. I was so careful filling in the bubbles on the Scantron with my Number 2 pencil, but being careful didn’t help. I didn’t get in.

I stopped looking for books at the library. I would continue to plug away at worksheets and long division. I would laugh with my friends on our walks home, throwing snowballs or, if it was warm, standing at the corner of Jackson and Gunderson discussing the world while the “el” rushed along two blocks away.

Leigh Botts lived close to a gas station. He wrote that it would ping whenever a car pulled up to get gas. He would listen to the pinging sound while he lay in bed, and sometimes between pings Leigh could hear the ocean and sea lions barking, and he would think of his dog Bandit and his father. His father took Bandit after the divorce.

One night, Leigh writes about being able to attend a writer’s luncheon to meet with a real author. Mrs. Badger, the author Leigh has lunch with, tells him how much she loved his story, “A Day on Dad’s Rig.”

“You write like you, and you did not try to imitate someone else. This is one mark of a good writer. Keep it up.”

At the end of Leigh’s journal entry, he writes that the gas station stopped pinging so he knows it’s late, but he wanted to write all of this down before he forgot it. He also writes that he wishes his dad were with him so Leigh could tell him about all of this. He wonders a lot throughout the book why his dad wouldn’t stay with the family.

The pinging reminded me of the “el” outside my bedroom window. I was in love with its sound. The trains were excitement and comfort, adventure and predictability all in one. After reading Dear Mr. Henshaw, I wondered if I could stay up and write long after the last train whooshed by. I never could, but I would keep a journal by my bed, and I would write a little, just like Leigh.

I’d write about school sometimes, and sometimes I’d write about going swimming in the summer and pinning my pool pass to my shorts, and crossing the bridge over the “el” and standing for a moment to look at the city’s skyline.

Sometimes I’d write down outfits I wore and outfits I planned to wear, and sometimes I’d write about going apple picking in Michigan and bringing so many apples home we filled up our fridge downstairs with them. We had crisp Jonathan apples every day for lunch, and sometimes my mom would make apple pie. I remembered once trying to explain why the mixture of cinnamon, butter, dough, and apples made me feel like I was standing in the Michigan apple orchard with my grandma, aunts and uncles, mom and dad, my brother and my cousins. All of us running and laughing and climbing ladders to reach the greenish red apples and the sun glittering through the green leaves seemed to taste like warm cinnamon, butter, and apples all mixed together.

Sometimes I wrote about morning glories.

Leigh’s father does come back, and while it’s something Leigh hopes for during most of the book, he also begins to realize that his dad is a wanderer, unpredictable, and always ready for an adventure on the road. So when his dad does stop by for a visit, and asks Leigh’s mom if there’s a chance they could get back together, the scene is awkward and sad and you realize the thing you want so badly is the thing that you cannot have, but that you’re okay. You’ll be okay. “I felt sad and a whole lot better at the same time,” Leigh writes about that visit.

A few years later, I started shelving books at the library next door. I did it reluctantly. I didn’t want to spend my summer days around books. I wanted to work at the Gap and get a discount on clothing. My mom, a librarian at one of the other branches in town, got this job for me, “because it’s right next door, Callie, and you have enough clothes from the Gap.”

So I became a shelver, and every day that I walked into the library and smelled the books and heard the crinkle of the covers as I picked them up, I remembered that girl who followed a command from her Barbie to start with the A’s. I was embarrassed thinking about that day, and when I shelved I tried to only pick up the adult fiction and nonfiction so I wouldn’t have to go near the little white house.

Mrs. Grinbard wasn’t there anymore. She passed away, which made walking around the library lonelier, and another reason I stuck to the books in the adult section. I didn’t want to go anywhere I’d walked with her.

But the Maze Branch is small and I was the only shelver, so eventually I had to put away picture books and Newberys, Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary. Sometimes, if I was feeling brave, I’d sit inside the little white house and find The Jolly Postman and read it, remembering the girl I once was, and the letters I’d thieved.

Sometimes I’d stand in front of Dear Mr. Henshaw, remembering Mrs. Grinbard and her fancy nails and high heels. I’d remember she taught me how to shelve the books and how fun I thought that was. I’d remember my twirl dress. I could feel it flying around me, like petals unfurling—just for a moment—before the dress bloomed and fell, asleep until I’d twirl again.

Remembering made me feel sad and a whole lot better at the same time

Photo by Garry Knight Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Callie Feyen.

A Writer’s Dream Book

—Sarah Smith, Executive Editor Prevention magazine; former Executive Editor Redbook magazine

- Poetry Prompt: Courage to Follow - July 24, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Being a Pilgrim and a Martha Stewart Homemaker - July 10, 2023

- Poetry Prompt: Monarch Butterfly’s Wildflower - June 19, 2023

Glynn says

I didn’t know until I read her obituary that she was also the author of the “Leave It to Beaver” stories, which means she had just as much influence on boys as she did on girls.

Callie Feyen says

I didn’t realize this, either. I agree, she reached so many children. I’m grateful for her stories.

Sandra Heska King says

I didn’t know that either. I loved the TV series.