Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938) is considered one of the most significant Russian poets of the 20th century. We have his much of his poetry today only because his wife, Nadezhda Khazina, protected them the only way she could at the time. She memorized them.

Mandelstam was born to a wealthy Polish-Jewish family in Warsaw. He studied for short periods at the Sorbonne, the University of Heidelberg, and the University of St. Petersburg, which excluded Jews, forcing him to convert to Methodism.

The pre-World War I period was a time of intense social, cultural, and political ferment in Russia and a time when poets were aligning themselves into “schools” and groups. Mandelstam was associated with the Poet’s Guild, a group that included Anna Ahkmatova. Also known as the Acmeists, these poets emphasized form and expression. This group was part of the Silver Age of Russian poetry, a period of intense creative activity from the 1890s to the 1920s.

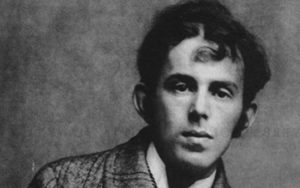

Osip Mandelstam

Mandelstam published his first collection of poetry, Stone, in 1913. Then came the war, the revolution, the civil war, and then the Soviet period. In 1922, he published a collection entitled Tristia, which set him at odds with both the Soviet state and pro-Soviet intellectuals and writers. In 1925, he published The Noise of Time, essays about his life. Somehow, he managed to publish three more volumes in 1928—a novella, Poems, and a group of critical essays on poetry. It’s believed that he was helped by a close associate of Stalin, a man named Nicolai Bukharin.

In 1933, he published a prose work, Journey to Armenia, that would be his last publication in his lifetime. A poem in which he described Stalin as a gleeful killer found its way to the Soviet leadership. He faced the possibility of death, but apparently Boris Pasternak and others were able to influence his sentence. Instead of execution, Mandelstam was sentenced to three years of exile in the Ural Mountains. His wife was allowed to accompany him.

He was released in 1937, just as the Great Soviet Purge was getting underway. Not allowed to live in the Soviet capital, the Mandelstams lived nearby. But his protector Bukharin had been arrested and sentenced to death. In 1938, Mandelstam was arrested again and sentenced to five years in the labor camps. This time, his wife could not come with him. He died from cold and hunger in a transit camp near Vladivostok.

This poem, one of 50 included in a new translation of Poems, would have been composed (and memorized by Nadezhda) in late 1936 or early 1937, while the Mandelstams were living in exile in the Ural Mountains.

The Birth of a Smile

In one way bitterly, in one way sweetly,

The far ends of its smile, all jokes aside,

Are lost to sight in oceanic chaos.

The child feels an unconquerable joy.

With the corners of its lips, it plays in glory

And a rainbow seam is already being stitched

For finding out what is reality.

Out of the water, land has risen on its paws—

The snail of the mouth washes up from under—

And one Atlantic moment strikes the eyes

Softly accompanied by praise and wonder.

Mandelstam’s poems address his friends and influences, the German language (a kind of tribute to a friend), poetry, an unknown soldier, and other themes. Included is a poem dedicated to Stalin, written in early 1937, perhaps in the hope of release from exile and the avoidance of future imprisonment. If so, it was a futile hope.

In an excellent essay included with the volume, translator Ilya Bernstein notes how Mandelstam composed his poems—by voice, creating them aloud, line by line. The poet’s notebooks have survived, but he “wrote” his poems orally first. That spoken creation was carried forward in how the poems were saved from likely destruction by the Stalinist regime, as his wife Nadezdha memorized and carried them in her mind and memory until they could be safely written down.

We read these poems in the knowledge of how the poet’s life ended, starving and freezing in a prisoner transit camp. The last letter to his wife begged her for food and a coat, which he never received. While he became one of the millions imprisoned and killed during the Soviet era, Mandelstam lives on in his poetry.

Related:

Anna Akhmatova and the Poetry of Resilience

A Reading of Osip Mandelstam in English, with Ilya Bernstein

Photo by Guiseppe Milo,, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Luci Shaw and “An Incremental Life” - April 3, 2025

- Ben Palpant Talks with 17 Poets About, Well, Poetry - April 1, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

Mary H Sayler says

Interesting articles, Glynn. I thought I had a copy of one of his books, but I can’t find it. Thanks for the reminders of Akhmatova and Tsvetaeva whose poetry I did find on my shelves but had not read in ages! The poems and prayers of people who have suffered carry such insight and power.

Sandra Heska King says

Thanks for this, Glynn. I’ve done some reading about the Mandelstams and the persecuted Russian poets. The volumes of poems they were able to memorize astounds me.