Flies can teach you a lot about poetry. Ask Robert Hudson.

Hudson has been a teacher, a clerk, an editor, a translator, a book designer, a proofreader, a publisher, a writer, a bookbinder, and a printer (with a certificate in printing by hand). With a master’s degree in comparative literature, he worked for 34 years as an editor for a major publisher. He loves poetry; he’s a member of the international Dante Alighieri Society and the Thomas Traherne Association. And he’s a member of the West Michigan Thomas Merton Society.

He also knows a lot about flies. And in The Poet and the Fly, he considers how the fly has served as an object for numerous poets over the centuries.

And poets have been writing about them, meditating upon them, using them as metaphors, following their trajectories, and symbolizing them for a very long time.

Hudson looks at seven poets who have written about flies, each in a different way. As you read this work, and occasionally marvel at what’s been written, you gradually realize that Hudson is not only talking about flies. He himself is using the subject of the fly to explain how and why poets write poetry.

English poet Thomas Traherne (1636-1674) was largely unknown as a poet until his life and works were plumbed in the 20th century. One of his meditations addresses the fly, and he uses the insect to examine human existence. William Oldys (1696-1761) was an antiquarian and bibliographer, known for serving as the first editor of Biographia Britannia and for his bibliographical work for the Duke of Norfolk. He rubbed shoulders with Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. He saw the fly as a symbol of mortality.

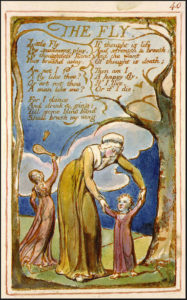

“The Fly” by William Blake

Poet and artist William Blake (1757-1827) used the fly as a symbol of imagination, while Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828) explored the fly as a symbol of compassion. He didn’t just write one haiku poem about the fly; he wrote more than 200. American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) used the fly to understand, or try to understand, the idea of the soul.

French poet Guillame Apollinaire (1880-1918) pondered the fly as a thing in an of itself, “hoping to find a hint of what its reality might be, to sense its mysterious essence, its thingness,” says Hudson. And Irish poet Robert Farren used the fly to tell a story.

Hudson has a fascinating essay on each of these poets, the works in which they used the fly, and how their thoughts about the fly helped shape some of the vital questions they wrestled with. And as he points out in an appendix, others have used the fly in their works, including William Shakespeare, Robert Herrick, Matsuo Basho, Thomas Gray, Goethe, Walt Whitman, Walter de la Mare, and Vachel Lindsay, among others. To give an idea of how well-researched this book is, the bibliography runs about 20 pages.

Robert Hudson

Hudson is the author of The Monk’s Record Player: Thomas Merton, Bob Dylan, and the Perilous Summer of 1966 (2018), Kiss the Earth When You Pray: The Father Zosima Poems (2016), The Art of the Almost Said: A Christian Writer’s Guide to Writing Poetry (2018), and Beyond Belief: What the Martyrs Said to God (2002). He also serves on the board of the Calvin College Center for Faith and Writing.

The next time a fly is buzzing about your head, or is desperately trying to make its way through a window pane to freedom, consider what many great poets have thought about the little pest. And consider what the fly has to say to us about why we write poetry. Well done, Robert Hudson; The Poet and the Fly is a rather profound work.

Photo by Michael Davis-Burchat, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

Ha ha! Funny timing.

I think the mortality image resonates most. Flies are always where death is. Now, if one wants to consider where Imagination comes in, I think that works, too. Where there is death, the fly comes as one of the first creatures to fold that death back into the life cycle. If that’s not like Imagination, I’m not sure what is. Poets, writers, artists, dancers… they can take the deepest darkness and bring forward some kind of Imaginative turn that feels, again, like life.

Glynn says

I’ve always associated flies with death as well (likely from reading too many murder mysteries or watching too many crime shows on television). What Hudson shows is the many variations on that theme, with additional possibilities as well (Apollinaire, true to the spirit of his age, looked at the fly as a thing in and of itself, separated from what we associate with it).

By the way, the essay on Emily Dickinson and the fly is worth the price of the book all by itself.

Katie Brewster says

“Poets, writers, artists, dancers. . .can take the deepest darkness and bring forward some kind of Imaginative turn that feels, again, like life.”

YES & Amen:)

Maureen says

True Fly

Hear

its buzz —

the friction

of two

wings in

flight

another

pair to

balance

by might —

untethered

to feed

to bite

and fight

——————-

How did you come to hear of this book, Glynn?

Dickinson’s poem “I heard a Fly buzz — when I died’ is here: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45703/i-heard-a-fly-buzz-when-i-died-591

Glynn says

Two Facebook friends were talking about it, so I clicked to see what it was about.

Thanks for the Dickinson poem!