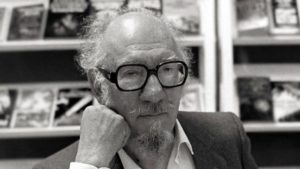

Julian Symons (1912-1994) was a prolific British writer producing books across multiple genres. He wrote 38 crime novels and shorter crime works; 33 works of biography, literary criticism, and history; two poetry collections; and numerous short stories. He also served as editor for eight collections of stories, poetry, and historical articles. The subject of his biographies included Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle, Oscar Wilde, Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, and W.H. Auden, among others.

Symons (pronounced like Simmons) is best known for his crime novels. He received two Edgar Awards from the Mystery Writers of America (MWA); in 1982 he was given the MWA Grand Master Award for his body of work.

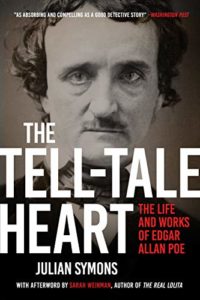

He also wrote a biography of Edgar Allan Poe. One of his edited anthologies was a collection of tales by Poe, published in 1980. But he had a problem with Poe, or rather, with the various biographies of Poe. Symons didn’t like any them. He was frustrated generally by biographies of authors that mixed biography and literary criticism of the author’s works. And that kind of biography was all he could find for Poe. So he did what any prolific writer would do.

He wrote his own biography of Poe.

Reissued in May of this year, The Tell-Tale Heart: The Life and Works of Edgar Allan Poe

The book is about 250 pages long, relatively short for a full biography (but then, Poe’s life was relatively short). Symons divided the work into two sections. The first, and longest, section is the biographical part, consisting of about 175 pages. The second part focuses on Poe’s literary criticism (and he could be a rather wicked if accurate critic), the poems, and the stories.

Dividing the man’s life and works, interestingly enough, allowed Symons to tell a better story of his life. Because Poe’s stories and poems were so original, it’s almost too easy for a consideration of them to overshadow the man’s life. But to understand his life is to see where the poems, stories, and criticism came from, and that is why Symons wrote the book the way he did. The reader still gets a complete picture, but the life comes first, and the works follow.

The Poe who arises from Symons’ hand is a man who first and foremost was determined to put Southern letters on the map, aiming to wrest control from the literary establishment in New York and New England (Poe aimed some rather pointed arrows at writers like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow). For his own writing, he wanted to be considered a poet. The poems were the important works; the stories were almost after-thoughts, almost dashed off primarily to raise funds. And he always needed money.

Julian Symons

Symons writes crisply and succinctly; he doesn’t waste words, and he avoids academic English. What resulted was a highly readable biography of a major figure in American letters. If there’s anyone writing today like Symons, I would suggest Peter Ackroyd, who’s almost as prolific and just about as wide-ranging in what he writes about. A major difference between them is that Ackroyd has never written crime fiction.

I particularly like the division between life and works. Symons doesn’t rigidly follow it; a few works are mentioned in some detail in the biographical section. But he makes Poe accessible in a way that many biographies don’t. The man and the writer come fully alive. Forty-two years after its inital publication, The Tell-Tale Heart remains a fine and entertaining biography.

Related:

The Belting Inheritance by Julian Symons

On the Haunting Remorse of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat”

Photo by Emily Reid,, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, Dancing King, and Dancing Prophet, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Katie Brewster says

Thank you for this helpful review, Glynn.

“The reader still gets the complete picture, but the life comes first and the works follow.”

“But he makes Poe accessible in a way many biographies don’t. The man and the writer come fully alive.”

Sounds like my kind of biographer:)

Glynn says

Thanks, Katie. Symons was, in many ways, a writer’s writer. His interests ranged over all kinds of books and fields. What intrigued me was his confidence. Dissatisfied with what he saw as the state of Poe biographies, he wrote his own. Long ago, Benjamin Franklin said you should write to please yourself. And that’s what Symons did.

Katie Brewster says

Symons sounds similar to a reviewer I often read;)

Megan Willome says

I noted the same lines Katie did. And I’m also intrigued by the separation.

I think it’s easy for literary criticism, especially by people who are more academics than writers, to try to meld biography to criticism in a way that is unhelpful. People like Symons, who also write their own stuff, seem to understand that the line between a writer and their work is both more ambiguous and more interesting that a simple 1:1 correlation.

Glynn says

I think you’re spot on, Megan. We spend so much time trying to identify where everything in a writer’s works (like Poe’s) comes from that we tend to discount the role of imagination. Oddly, I found Symons’ approach more respectful of the reader, leaving it to the reader to decide which elements of a writer’s life might have been significant for the work the writer produced.