Justin Hamm, a native of central Illinois, has published a photography book, Midwestern, and three poetry collections, American Ephemeral, Lessons in Ruin, and The Inheritance. His poems, stories, and photographs have been included in anthologies and published in a number of literary journals and magazines, including Nimrod, The Midwest Quarterly, Sugar House Review, Pittsburgh Poetry Review, and others. He’s also had several solo photography exhibitions. He now lives near what he calls “Mark Twain country,” which is northeastern Missouri, about 120 miles (or two hours) north of where I live.

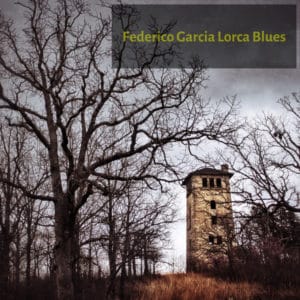

He’s released an album of recorded poems entitled Federico Garcia Lorca Blues. It’s more than recorded poetry; it’s orchestrated with simple music and sound effects and enhanced with Hamm’s deep and resonant voice. I decided to listen to it in my backyard, and it turned into an almost perfect “poetic experience.” Later, I talked with Justin about poetry, favorite poets, and the album.

Justin, I sat in my backyard to listen to Federico Garcia Lorca Blues. Where I live is what everyone calls an inner suburb of St. Louis, but it’s really a slightly more molded and shaped edge of the Ozark foothills, not terribly different from your own hometown. It’s a warm but not hot summer’s day, with a slight breeze nudging the zinnias and coleus and only lightly disturbing small butterflies, moths, and an occasional hummingbird hovering above the flowers. It’s an almost ideal way to listen to this multi-genre album.

In The Inheritance, you combined poems and photographs. The photographs were themselves poems, speaking as eloquently as the simple yet profound words of the written poems. What draws you to photography?

For me, in either medium, the initial motivation is as simple as “I experienced something that made me feel, so now I’m making this thing to help you feel it too.” The skill is in figuring out how to present or adorn a photograph or poem, so the feeling comes through. To accurately communicate what I’m seeing and experiencing, I might need to transcend the literal. That process of figuring out how to use craft to portray an emotional truth keeps me interested in writing and photography.

In Federico Garcia Lorca Blues, you combine non-visual media—words, music, the soundtrack of a storm—to create a very visual artistic experience. This isn’t you reading a poem at a microphone or performing at the improv; this is a carefully constructed combination of words, music, sounds, repetition, and especially that deep, resonant voice. It moves the listener to a very different place than if one only read the poems. How did you arrive at the combination?

For the project to be worth the time and effort, it needed to go beyond what I could do with an iPhone in my basement. It had to add to the experience of the poems and present them in a different context—otherwise, why would it be any different than just attending a reading? I’m not a slam or performance poet. My delivery alone wouldn’t justify making an album. But at the same time, I do have some strengths as a reader that can be presented favorably as one part of a larger mix. That was the thought process.

As to the nuts and bolts, my friend Dave Reetz, a really talented musician, and I talked a lot about how we wanted each track to sound. I’d go in and do the vocal parts, and the tempo of each track would be set by the natural pace of my reading. I’ve done most of these poems many, many times in front of an audience, so they had an established cadence already. From there we’d talk about what a particular poem was saying and what images stuck out and try to imagine a sound to complement that. Dave has some great recording software that includes a variety of prerecorded studio loops. He’d begin with those, and if he couldn’t find what we wanted, he’d improvise and record a part himself. For instance, in “Pay Phones in the Underworld,” I told him I was hearing something like “St. James Infirmary” behind it. He came up with an instrumental in a similar style and played the slide guitar himself. He also spent a lot of time getting the tempo right and syncing up flourishes like the thunder or the harmonica coming in on the word “crying” in the first track.

There are seven tracks, three of which use four poems from The Inheritance. The combining of two of the poems in one track—“Storm, Rural Missouri” and “I Will Tell You Where I’ve Been”—is especially powerful. They become one poem, sewn together by the repetition of key words from “Storm, Rural Missouri.” How did you know to fit these two poems together?

Those two poems came out of the same series of writing sessions. They might even have had a common ancestor poem out of which they each developed; I can’t remember exactly. But the storms and the tone and the rural imagery connect them. They’re so clearly about the same landscape and the same type of people that it made sense for me to bring the track back around to invite the listener to consider that relationship.

That track also uses a soundtrack of storm and rain, a guitar, and a harmonica. Is that you playing the musical instruments?

I wish. Dave put that track together using prerecorded loops. The instrument in the first song is actually a banjo. He tried to get me to record my own ukulele part for one of the poems, but the loops and his playing are so professional that

I worried my inferior playing would sound out of place on the album.

The title track, “Federico Garcia Lorca Blues,” takes the listener from Andalusia to the streets of Chicago, the abandoned siloes of the Ozarks, and even to a grandfather getting his insulin shots. This poem sounds especially personal, as if you’re sitting by the grandfather’s bedside. Is Garcia Lorca a favorite poet?

I appreciate your insights here, Glynn. It is personal. I watched my grandfather take his insulin a thousand times as a kid, so that’s a very specific memory for me. Now it’s my daughters who watch me do the same.

I didn’t know Lorca’s poetry until a few years ago. That’s one of the best parts about literature. You can feel as though you’re fairly well-read and then come across a titan of a writer or poet you didn’t know about, and it’s like discovering the entire universe over again. That’s what finding Lorca was for me. He’s so full of originality and mystery and dark beauty. And passion! He can be difficult, but he always makes a sort of “poetic sense.” Even the strangest of his images or metaphors leaves you with a feeling of inevitability. Which is a long way of saying, yes, Lorca is in my personal pantheon of poets. I have spent a lot of time reading English translations of his work and biographies about his life. One day I’d like to be able to read him in Spanish.

Poetry was spoken aloud long before it was written down. Reading a poem like “The Carpenter” and hearing you speak it accompanied by a pounding hammer are very different experiences, even if the same words are used. These aren’t songs, but neither are they only poems read aloud. These seem like poems performed and almost choreographed. What brought you to this kind of art form?

Justin Hamm

Dave’s knowledge of audio had a lot to do with it. He had ideas for subtle touches that really gave the tracks some extra texture. But pairing poetry with other art forms is a goal I’m always pursuing. Obviously, I have the poetry/photography show, which has been traveling different galleries for a couple of years now. And I’ve worked with a graphic artist on broadsides. I make digital collages, and I’ve been trying to find a way to work poetry into those. Eventually, I’d even like to make a short poetry film. I like the idea of taking poems to places besides the pages of a literary magazine where, after the initial release, it might go unread forever. I’m always seeking interesting ways to get it to the eyes and ears of more people.

I loved listening to “Gratitude for the Poets,” thanking them for all they’ve brought to the world. Did you have specific poets in mind when you wrote this? Do you have favorite poets or poetry collections?

I did have a couple of specific poets in mind—Frost, Lorca, and Gwendolyn Brooks are all referenced. And I participate in a weekly virtual open mic that has been really good for my sanity during the tumult that 2020 has been. So there’s a shout out to that group. And, of course, even if the imagery itself didn’t reference them, I was thinking of all the poets who have influenced me through their work or in real life.

As to favorites: Linda Pastan. Raymond Carver. Lorca. Robert Bly and James Wright. Cornelius Eady. Shel Silverstein. Nikki Finney. Sharon Olds. Neruda. Frank Stanford.

I feel like I give a different list every time I’m asked. The truth is, at any given moment, if I’m reading a great poem, whoever wrote it is automatically my favorite poet.

Related:

Poets and Poems: Justin Hamm and The Inheritance

Photo by Yancy, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

Bethany R. says

Thank you for sharing this. Fascinating how he’s combined mediums and methods to get his thoughts and feelings across. I like what he says about giving a different list of favorite poets every time. I sometimes feel like I have to be “loyal” to my favorites whenever I’m asked, but of course, our preferences are malleable.