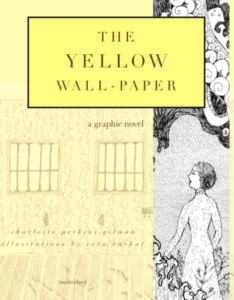

We asked Sara Barkat, illustrator of The Yellow Wall-Paper: A Graphic Novel, to write about how to do literary analysis, using the story The Yellow Wall-Paper as its central example.

The tale, which lends itself to broad interpretations, seemed perfect for the point you’ll see made here: stories have both flexibility and boundary for what can be said about them. And stories beg to be heard for what they are, even while inviting conversation about what that might be.

Whatever you see in both the essay and its analysis portions that follow—the formatting, the punctuation, the form as a whole— has been intended. We invite you to see it as an invitation to you, to think more deeply than you’ve been invited to in the past, about what the nature of literary analysis is and what it can be.

Literary Analysis Is a Conversation Between Writer and Reader

Literary analysis. For every story, there are things unsaid. What the story skips over or leaves oblique, or misdirects with (if you have an unreliable narrator, like in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wall-paper”, for example). Any successful analysis gets at those in-between moments, figuring how they fit into the text of the story, and how that combination of text and subtext informs the shape of the story as a whole.

Of course you have to start with the text. What the story actually says. Those are the hints, the evidence to the mystery. You can’t figure out meaning (potential meanings—because there are always multiple possible interpretations) without first taking a good look at what’s actually there, spelled out, and in what context.

But to leave it at just that is to only brush the surface of literary analysis. It’s only summary. The interplay between text and subtext and more or less possible interpretations are like expanding ripples in a pond around which a stone (the story) has been dropped. The closer in the ring, the more “justified” the interpretation. The further you get, the more you have to reach. That’s not to say you can’t go there at all, though. You can interpret a story any which way, as long as it all ties back to text in the end, as long as you’re still within the realm of potential, as long as you’re still looking at the stone and not some other thing you dropped into a pond while you forget about the stone. (Otherwise, you’ve moved into the realm of adaptation.)

i.

The simplest textual interpretation of The Yellow Wallpaper is that our unnamed narrator is taken by her husband to a rented “ancestral hall” in the country—

[note the connection made right at the beginning with inescapable history; you’ve also got the house characterized by our narrator as a “haunted house.”]

—after she has a mental breakdown. (“temporary nervous depression”)—(not so temporary as all that; she gets worse, not better, in her isolation. [hear the resonances in her initial description of the grounds: “hedges and walls and gates that lock … separate little houses”] … Isolation from society as a whole. And the people she’s with—her husband and his sister—don’t listen to her)

[And don’t all people need others to recognize them in order to feel real? No wonder she created a woman in the wall-paper (to alleviate her own loneliness)]

[on a larger scale: the author’s critique of society: there always were women in the wallpaper. Who couldn’t speak. Most people just don’t want to see them]

[No wonder she (the narrator)(the author?) tells her story to you, reader of her unfortunate journal]

She’s put into a room she doesn’t like, with wallpaper she hates. She wanted a different one, but “John would not hear of it.” John has many logical reasons for why his choice is better. But she wanted the one with the flowers, the one that “opened onto the piazza”, the one she picked [after all, isn’t this “getting better” business about her?]

[No.]

The wallpaper then becomes the metaphorical focal point for her frustrations with her situation, her feelings of being unheard in her own marriage (“John laughs at me of course, but one expects that in marriage.”)(“I get unreasonably angry with John sometimes … I think it is due to this nervous condition”—she doesn’t want to admit that she might actually have something to be angry about— not at first, because that leads to recognition that there’s a problem she can’t fix) by just. Trying harder.

[She tries to tell herself everything is fine. Or: she wants to complain but she knows she has nothing to complain about in the eyes of society.]

[And controlling herself makes her feel tired]

—until her projections take on symbolic life of their own.

[You trip over symbolism wherever you go. The curves of the wall-paper “commit suicide” the way she would never dream of]

[because “a step like that is improper and might be misconstrued”]

[the wall-paper disregards the principles of design. Flies in the face of art.]

“The faint figure seemed to shake the pattern [of the bars] just as if she wanted to get out”

A destructive kind of coping mechanism. (She’s so intelligent and imaginative, but has nothing intellectually stimulating to interact with)

In the end, our narrator takes the only way out she can—into her mind; into the power of her own story. But it’s an ambiguous victory.

It’s a story about what can’t be “felt and seen and put down in figures.” Something that doesn’t fit within (ironically enough) the sphere of academic writing, the tradition of logical analysis.

[You could take one tack, and interpret the story through the lens of feminism, particularly the tension between traditionally male-dominated spheres of writing and how those kinds of speech are justified as important, while fiction—always associated more with the feminine—is treated as frivolous. In need of justification. You must remember, the author herself chose to write her critique of society through the lens of story, not essay; using a female narrator who self-identifies as a writer (though this is dismissed by those around her). + The conceit of “The Yellow Wall-paper” as being a journal, a literally crafted piece of writing—drawing attention to the conventions of narrative. To narrative itself.1]

[this is the one i am most fond of. because stories and all that metatextual interest means a lot to me.

The story can be about more than that. How about: she knows she is ill but everyone keeps telling her she’s fine and making too much of it and if she just tries harder — no?

The critique of medical treatment and connection with mental illness is also very highlighted. The author herself once claimed that’s what the story was all about.]

[in an essay to explain the story to others]

[where she said: it was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy2]

ii.

Hop outward to the next ripple. Turn the genre around. The story is always horror, but in what way? Perhaps the house always was haunted. Literally. It fits the genre of horror to have only one character, our hero, who notices something is wrong, even as the pernicious influence of this haunted wall-paper creeps its way into their brains…

“why should [the house] be let so cheaply? And why have stood so long untenanted?” it’s far away from the village, just the perfect place for a haunted house to be. Nowhere to run to. “there’s something strange about the house” (she can feel it) [but he said what she felt was a draught, and shut the window]

the room has obviously been occupied before. By whom? Perhaps an individual with reason to be unhappy. Something to do with the scratches on the floor, the bars on the window, the “rings and things in the wall” and the bed bolted down.

[in our previous interpretation, this individual could be metaphorically haunting our narrator. Perhaps in this case she is literally haunting our hero.]

[perhaps it is the ghost of a woman who committed suicide, the paper holding her here still]

“the pattern lolls like a broken neck”

“at first [John] meant to repaper the room” (but then he changed his mind)(said she was letting it get the better of her)

It’s a narrative convention of horror to have the story take the form of a journal, written in first person; someone driven slowly mad by an inescapable horror, some supernatural something that —of course— was only a product of the imagination. Surely we, dear readers, know better.

Of course our hero is exposed to the room more than the other two, as she is the invalid. “John is kept in town very often by serious cases” —and so maybe it affects him less.

[in our previous interpretations, one could take this as a metaphor about how both men and women are caught in the same constricting society, but men have more ability to try to pretend, more space to move and run and forget—

but that’s the interesting thing about supernatural horror. The monster can have all sorts of resonance with reality. That’s what makes it scary]

A wall-paper with a design that is NEVER repeated? How likely is that, for any mass-produced or even hand-painted item? It stretches the bounds of credulity that it is so unutterably incomprehensible.

And of course. It moves. Especially when the light changes. In moonlight, its true nature is revealed. Things in the paper. A woman crawling up and down. Behind the bars. Shaking it. The pattern moves. trying to get out

John thinks she’s getting better. “You are gaining flesh and color, your appetite is better, I feel really much easier about you” he’s a doctor, he should know. But she doesn’t weigh a bit more… (someone’s perception has been tampered with. Doesn’t mean it’s hers)

John and Jennie begin to have inexplicable looks. John and Jennie stare at the paper. And the yellow smell begins to move out of the room, through the house—out of the house,

“even when I go to ride, if I turn my head suddenly and surprise it— there is that smell!” It’s the color of the paper. A yellow smell. Perhaps burning the house, as she thought of but didn’t do, really was the right answer.

As for John: “I don’t wonder he acts so, sleeping under this paper for three months. It only interests me,” our doomed hero confesses, “but I feel sure John and Jennie are secretly affected by it.”

iii.

And a ripple outward from that. Let’s pull in more history, this time. Let’s turn the horror in another direction. The dyes used in wallpaper Victorian times had arsenic in it, and was known to have killed. The smell of the wall-paper, that gets worse when it rains? The way the yellow pigment rubs off on our leading lady’s clothing, and her husband’s too? Even the fact that it seems to affect our lady more than John, because she’s exposed to the toxin more. He keeps staying in town even over the night more and more.

Three months is surely enough time to be poisoned.

o-O-o

Here, you see, we begin to move from what is textually and subtextually evident—to readers in the 21st century—into specific cultural, historical context. (Another form of subtext, but one that is lost to us now without a little digging). For a story about poisoning, one would expect a few more unambiguous references to carry you along. But, of course, Gilman’s readers would know all about arsenic and poisonous wallpaper.3

It’s an interesting theory. But to leave it at that is to stop at a historical analysis through the lens of literature. You may argue that our leading lady is literally getting poisoned by arsenic. (possible symptoms: drowsiness, confusion; sure)(but many more than that too, and if that was the point of the story, you’d see more symptoms featured—and probably have less mysterious women crawling around. That’s an important symbol not explicable by a scientific look at arsenic poisoning)4

To really push forward, and turn this theory into a literary analysis, one still needs to see what’s in the text, and what potential meanings Gilman’s story could create from this cultural context. What it means that society continues to churn out pretty, “useful” things to help (?) other people (to make money), knowing it harms them. How people in society know it will harm them and use it anyway, lag behind doing anything about it.

Now, here, the way society kills has been made explicit. (That’s the best kind of metaphor, though, isn’t it. Gilman is talking about poisonous wallpaper. Literally. She’s expanding on that to create a metaphor about how society treats women. Or. How society treats anyone, and everyone, merrily pushing forward in its destructive impulses.)

Oh, sure, the producers of wallpaper were merely being careless (knowingly? That’s not carelessness anymore, that’s denial, or maliciousness, or greed).

Isn’t that what this story is about? The inexcusable behaviour of those given the power to be in charge of life and death? [medically, or otherwise][what they try to sell you]

[well, that’s a question. Proving it one way or another, through reference to the text—that’s literary analysis.]

iv.

So. Adaptation. Any literary analysis that strays too far from the nexus of the story, the text itself and associated subtext, is no longer literary analysis but adaptation.

- This includes such oft-used “interpretations” as “it was just a dream”—[barring, of course, the few stories with textual or subtextual evidence to make that the logical conclusion. Take Alice in Wonderland or Through the Looking-Glass, which explicitly state it was all a dream, and where dream-logic is used and incorporated into the story to such an extent that it takes contortions to argue it is anything else]

In other words. I could also argue? (though with no textual evidence whatsoever) that our female human was in fact abducted by aliens at the beginning of the story, which posed as her husband and his sister (of course she can still tell there is something off about them). The yellow wall-paper is, of course, our female human’s only way of interpreting the complete alienness of the ship’s illusion, and when she sees bars in the wall-paper she is seeing bars, because they are bars.

And there are other women in cells next to her.

They are doing an experiment, of course. A medical experiment. Making her take what she thinks are “tonics” but are really not, and never were. Etcetera. Etcetera. You can see the thematic resonances here. In some ways it contains echoes of the same story, however you interpret it.

It’s a story I would love to read, or watch. But it is not “The Yellow Wall-Paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. It has traveled too far along the widening ripples, far off in the water, far away from the stone, our original story.

Not in meaning, necessarily. [Not in the thematics. But. If someone actually tries to argue “The Yellow Wall-Paper” is a story about alien abduction, they… are wrong]

Literary analysis. For every story, there are things unsaid. There are things that can be said, and there are things that can’t be said without acknowledgment that you are, in fact, telling your own story now. And (as long as you admit that) why should it be a bad thing? The sentiment is one that I think our author, and narrator, would support wholeheartedly.

After all, everyone needs to speak. To be heard. There’s importance in telling, and that includes a telling that takes someone else’s story as a jumping off point, to get out, and tell your own.

Photo by Andrew E. Larsen, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Sara Barkat.

_________

“Sara’s stunning, heartbreaking, and relevant illustrations help to tell a difficult, haunting story. I will return to the story, as I do with all those stories I love, again and again.”

—Callie Feyen, teacher

References

i.

“ancestral hall” + “haunted house” (The Yellow Wall-Paper: A Graphic Novel by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, illustrated by Sara Barkat, page 7)

“temporary nervous depression” (page 8)

“hedges and walls and gates that lock … separate little houses” (page 9)

“John would not hear of it.” + “opened onto the piazza” (page 12)

“John laughs at me of course, but one expects that in marriage.” (page 7)

“I get unreasonably angry with John sometimes … I think it is due to this nervous condition” [And controlling herself makes her feel tired] (page 11)

[the shapes of the wallpaper] “commit suicide” (page 16)

“a step like that [jumping out a window] is improper and might be misconstrued” (page 100)

[the wall-paper disregards the principles of design. Flies in the face of art.] (page 37)

“The faint figure seemed to shake the pattern [of the bars] just as if she wanted to get out” (page 53)

[John scoffs at what can’t be] “felt and seen and put down in figures.” (page 7)

1 See:

> interview by Megan Willome of illustrator Sara Barkat

- “Feminist theory takes note that in much of the writing about history, philosophy and psychology, the male experience is usually the focus. … Subjectivity is an attempt to see history from the perspective of the individuals who lived that history … a subjective approach [is] a qualitative rather than quantitative study [where] emotion is taken seriously”

- “as a feminine form also shape the diary novel as a feminine form – interiority, exploration of close relationships, the woman as one who is observed and on display, but not quite a public figure. … ‘That women’s concerns and desires are important, and that a woman’s story can be the center of a narrative, are the claims that make eighteenth-century women’s fictions ‘romantic’ …[and] still devalued in comparison to other genre fiction’ (Spencer, Jane. “Women writers and the eighteenth-century novel.”) … “Letter,” “write,” and “read” … point to a self-awareness of the epistolary form.”

- Katy Frank, “The Mutual Constitution of Femininity and Privacy in 18th Century Epistolary Novels”

2 “[The story] was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy” (“Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper”, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman)

ii.

“why should [the house] be let so cheaply? And why have stood so long untenanted?” (The Yellow Wall-Paper: A Graphic Novel by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, illustrated by Sara Barkat, page 7)

“there’s something strange about the house” [but he said what she felt was a draught, and shut the window] (page 11)

“rings and things in the wall” (page 14)

“the pattern lolls like a broken neck” (page 25)

“at first [John] meant to repaper the room” (page 20)

“John is kept in town very often by serious cases” (page 35)

“You are gaining flesh and color, your appetite is better, I feel really much easier about you” (page 55)

But she doesn’t weigh a bit more [the narrator tries to tell John] (page 56)

John and Jennie begin to have inexplicable looks (page 67)

John and Jennie stare at the paper (page 68-69)

“even when I go to ride, if I turn my head suddenly and surprise it— there is that smell!” (page 77)

She considers burning the house (page 79)

“I don’t wonder he acts so, sleeping under this paper for three months. It only interests me, but I feel sure John and Jennie are secretly affected by it.” (page 89)

iii.

[the arsenic-based pigment, first used to create green] “could also be mixed to create bright yellows and rich blues.”

“Initial reports of wallpaper poisoning were shared in medical literature in the late 1850s”

“In some kind of disconnect, people believed that only by licking the walls would they get poisoned, or only by the green colors … [but] Left untouched, Victorian wallpaper could still release flakes of arsenic into the air or produce arsenical gas when conditions were damp.”

4 symptoms of arsenic poisoning

iv.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

“[Alice] found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

‘Wake up, Alice dear!’ said her sister; ‘Why, what a long sleep you’ve had!’

‘Oh, I’ve had such a curious dream!’ said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, ‘It was a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it’s getting late.’ So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.”

Related

The Yellow Wallpaper Characters List

The Yellow Wallpaper Full Text

The Yellow Wall-Paper: A Graphic Novel Writing Series

Prompt 1-Out of One Window I Can See

Prompt 2-I Would Say a Haunted

- Good News—It’s Okay to Write a Plot Without Conflict - December 8, 2022

- Can a Machine Write Better Than You?—5 Best (And Worst) AI Poem Generators - September 26, 2022

- What to Eat With Dracula: Paprika Hendl - May 17, 2022

Leave a Reply