The Yellow Wallpaper Analysis

The Yellow Wall-Paper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman is a horror story, a feminist text, a study of the relationship between author and character and writing itself—in a tale where the main character is a writer, creating the story the reader is reading, and where Gilman herself created the work based on her own experiences. It is deceptively simple in its execution, but it is complex for all that.

To begin, it may be alluring to imagine that the wall-paper, so hideous in its power, can be clearly delineated: that it is always in opposition to the narrator, always aligned with her antagonist, that there is an easy way to place blame, but the story purposefully defies this imagining.

The wall-paper, the narrator reminds us, “only interests me, but I feel sure John and Jennie are secretly affected by it,” referring to the three characters central to the text, and which the events of the story revolve around: the narrator, her husband, and her husband’s sister. Perhaps the reader might be interested in the idea that the narrator, who ultimately proves herself unreliable, can be discounted altogether—perhaps the reader might find the theory that she was always in a mental institution an attractive one. Yet the very structure of the story itself must, in fact, disprove that.

The unnamed narrator’s existence in the story is so carefully controlled. When the tale begins, she has been brought by her husband to a rented house where the three will stay the summer (along with the main character’s newborn baby and whomever is caring for the child), so the main character can recover from her nervous breakdown. She’s directed to take air and exercise and tonics, at her husband (also her doctor’s) bequest, and implored to get well for his sake, instead of for hers. She’s forced to lie down for an hour after each meal, in the room she never wanted to choose anyway, staring at the paper she hates, and not allowed her vocation of writing.

It’s easy, knowing the circumstances, to vilify her husband and see the narrator as the injured party, to empathize and root for her. The conversations the two have throughout the book add to that as well; as the narrator gets worse from the rest cure that’s meant to make her better, she tries multiple times to tell her husband that it isn’t working, and to plead for him to allow her friends over, or to go somewhere else, but everything he’s saying is so carefully calculated in order to dismiss everything she’s trying to get him to understand. Here the narrator shows that her voice is being dismissed. If that were the only facet to the story, however, it would not have the complexity and lasting power that it does.

Because, of course, the unnamed narrator is the narrator. The whole conceit of the story is that you, the reader, are reading what she has written, furtively, (slyly, the narrator herself will put it) though others don’t want her to write. The end power of how to frame the story belongs with the narrator, and thus any narrative tricks used must be understood as self-aware, purposefully crafted by the character in the story—so that even craft itself becomes plot.

The main character is not named. The only named characters are her husband John, and Jennie, his sister. Then there’s Mary: “It is fortunate Mary is so good with the baby,” the narrator thinks early on, but this mysterious personage (perhaps a nanny?) is never mentioned again. Then, at the end, the narrator says to John that she’s gotten out of the wall-paper “in spite of you and Jane?” You as the reader may think “Jane” is meant to refer to Jennie; after all, the names start with the same letter—and we know Jennie as a player in the story, while there has been no Jane at all up till now.

This is the moment of the main character’s greatest break or disconnect from reality—and yet in remembering that she is in fact the narrator still, it brings a level of artifice. It reminds you that within the story this is all something the character is writing down: and near the end, where she’s totally of it, you still have to believe that she’s writing this down. It adds self-awareness to the ending, that I am writing this story and I made a mistake—or did I? It’s a textual way of showing how out of it she is, but it’s so precisely done that it almost does the opposite at the same time. It’s no accident that it appears in her last speech. There’s a calculated element in its appearance there. The question mark after it talks straight to the reader—it’s not Jane, you know it’s not Jane, right?

This is preceded by a much more coherent, at least in its narrative elements, passage where she thinks about the fact that soon John will be in the room. She is now alone, thinking to herself, but soon she will have a viewer, another actor in the play, another person to account to. And she thinks of John, “I want to astonish him.”

All through the story nothing she’s tried to tell him has gotten through. Nothing she’s done has ever managed to gain his extended interest, let alone his astonishment. She starts the narrative relieved that he says her case isn’t serious, but is also frustrated that he doesn’t believe she’s sick. (“Bless her little heart!” he says once, “she shall be as sick as she pleases!”) And her husband is constantly leaving her side to go tend to more serious cases—sometimes even overnight. She feels terrible at the way she’s being treated, yet constantly reminds the reader, and herself, that John loves her and is not trying to be malicious. Yet at some point that ceases to hold weight against the very fact of her own lived experience, which she is unable to verbally convey to him.

When she later writes out her thoughts and explains how she tried to talk to him, she says, “and I did not make a out very good case for myself, for I was crying before I had finished.” Her very frustration at being ignored is becoming another tool used to discredit her, and her feelings of overwhelm are minimized. He says he will whitewash the basement for her, but she is not living in the basement, she is living, mostly alone, in the room with the horrible wall-paper, which notably John does not have to stay and interact with as much. He has more relief from it, in that he can choose whether to be there, to stay out late, to avoid it. Symbolically, if the wall-paper is society, that “only interests [the main character] … but… John and Jennie are secretly affected by it,” you can see how he is dealing with his part in it—by pretending that the wall-paper can have no real affect: on her, or on him, or anyone. It’s a real blinding, purposefully, to himself. Interestingly, the main character points the way regarding this issue; when the wallpaper strangles the women, it “makes their eyes white,” or blinds them, as well.

Why Jane? It’s literally erasing Jennie as a character—purposefully referring to her by the wrong name. And at the hands of our suffering hero, no less?

Consider this: why did the main character never pay attention to Jennie? They might have been able to support each other, but for various reasons, and partially because the main character was dismissive of Jennie, which you see in her description of her—so dismissive because Jennie is happy to be a housewife, “and hopes for no better profession”—they never were able to do that for each other. She thinks that Jennie believes it’s the writing that’s making her sick—that is, if she just conformed, and acted the right way, there would be no problem. Thus, she dismisses her out of hand as a source of help or solidarity. She never saw the woman as another person whose interior life might be worth encountering, and so, in effect, treats Jennie the same way John treats her.

Interestingly there is that moment very late on in the story where Jennie sees the paper half pulled off and “looked at the wall in amazement.” (Here, she is astonished by the main character as John isn’t until the end, but her reaction, and the entire interaction, is a positive one.) The main character tells her she pulled it down “out of pure spite at the vicious thing” and Jennie laughs and says she “wouldn’t mind doing it herself,” but that the main character “must not get tired.” This is interpreted by the now incredibly paranoid main character as a false statement, but consider, if it were true, both the plot ramifications, and the symbolic ramifications. It implies that though Jennie, it seems, would not have thought to start attacking the paper she would have happily done so if given the chance: but she never was.

Thus all characters are isolated from each other.

In the climactic scene, the main character locks herself into the room and throws the key down by the front steps, under a plantain leaf. When John tries to get in, he can’t, and the narrator tells the reader how she told him where the key was, and said it “so often that he had to go and see.” In the end she has forced him to listen to her, forced him to step through her own shoes of being directed in his movements by another, and in the end, yes, she manages to astonish him. Yet for what? She has not gained any real triumph. She still has to “creep over him every time!” As for him, he ends the story insensible—no longer able to speak, or stop her from speaking, but still, and more fully, blinded than ever before—the truth, it seems, was too much for him.

You, the reader, must know that the unreliability is part of the artifice of the story, but to throw out everything she is experiencing and conveying, even if it’s in coded, symbolic language, is to do the same to her as John did when she tried to explain herself: to add a completely other interpretation that wipes out everything about her own experience. This is why the theory that she was always in a mental institution—a cop-out as a writing device anyway, second only to “it was all a dream”—becomes really frightening, for it places you the reader in the position of antagonist toward the text. The whole problem is people aren’t taking the main character seriously. As an interpretation, that theory does her a disservice by saying that she was entirely wrong from the beginning of the entire sequence of events.

Maybe this summerhouse was a specific choice by her husband, and that room was a space that had previously housed a mental patient in its wall-papered confines, and he’s trying to frame it as something different. That could be plausible, but what is not plausible is to take small instances of the narrator’s unreliability that purposefully increase in unreliability throughout the text, and say she was in an institution the whole time. To do so throws out the text of the story itself, the narrative momentum of the story, and everything in it—and you are left with no story at all, only an excuse to disregard it, and any truth it has. (The text, you might say—the narrator’s literal, explicitly-written account of herself—had become hysterical—was crying before it had finished—so of course it could not have been making true observations on any matter, at any time whatsoever.)

The text itself rails against you for doing that very thing. You must believe the power of the main character’s experience or you are not actually reading the story at all, you are over-telling it with your own narrative, one that minimizes the “imaginative power and … story-making” of her narration out of fear of it.

Perhaps that is the true horror of the story of the yellow wall-paper. It would be so much more palatable if the blame could be pinned down: to John, for disregarding the main character; to Jennie, for helping him, to the main character herself, for being tricksy and unreliable and mad the whole time. But none of those simple answers are possible: the wall-paper, yellow and sinister and changing, affects not just one of the characters, but all of them: and, as the reader may well discover, all of us, too.

Related

How to Do Literary Analysis: An Experimental Reflection Based on The Yellow Wall-Paper

The Yellow Wallpaper Characters List

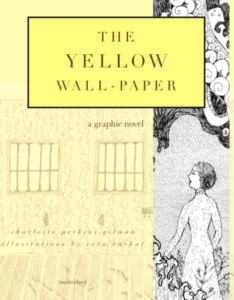

Photo by dr.larsbergmann, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Sara Barkat.

“Sara’s stunning, heartbreaking, and relevant illustrations help to tell a difficult, haunting story. I will return to the story, as I do with all those stories I love, again and again.”

—Callie Feyen, teacher

- Good News—It’s Okay to Write a Plot Without Conflict - December 8, 2022

- Can a Machine Write Better Than You?—5 Best (And Worst) AI Poem Generators - September 26, 2022

- What to Eat With Dracula: Paprika Hendl - May 17, 2022

Will Willingham says

Well, and see, this is why we need people like you around us. 🙂 I get caught up in one part of the story and missed altogether that Jennie had been misnamed in that critical moment…