“Are you still writing?”

I get this question every time I see a doctor. They ask it as if writing were one of my hobbies, like cycling, though they never ask about that and I always wish they would.

The unnamed narrator in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wall-Paper, published in 1892, is also a writer, and her writing is similarly dismissed, especially by her husband (who also happens to be her doctor).

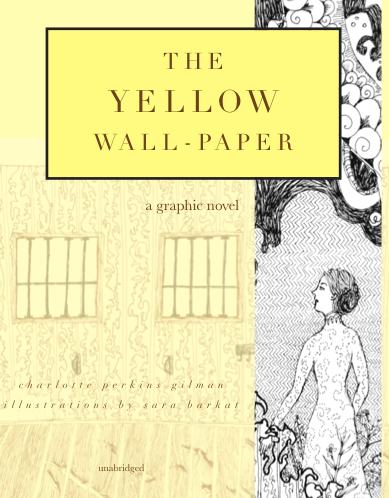

“Her family doesn’t see it as legitimate work, like it’s some strange hobby,” said Sara Barkat, who is the illustrator of a just-published graphic novel edition of the story. Sara is also the editor of T.S. Poetry Press’s reissue of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Her intaglio has been exhibited at the Ossining Arts Council gallery and the Purchase Maass Gallery.

Barkat began illustrating the story, which she’d first encountered in an AP English class, for fun.

“I was in a boring place on a vacation. I thought, ‘I know what would be funny — I’ll start drawing “The Yellow Wall-Paper” as a graphic novel,’” she said. “I was surprised nobody else had turned it into a graphic novel, but that makes sense, because if you don’t make up strong visuals to go with it you’re stuck drawing wallpaper, and I could see why someone wouldn’t want to draw that.”

In the story, a woman goes to a summer house with her husband and is forced to rest in the top room, covered in horrid yellow wallpaper, which, shall we say, changes her for good.

The story has always had fans and detractors. It was beloved by H.P. Lovecraft, one of America’s earliest and best practitioners of what’s known as weird fiction, filled with streams of the supernatural and of horror.

“[‘The Yellow Wall-Paper’] doesn’t seem on the surface to be a horror story, necessarily. The ending comes almost as a surprise, but then not, because it’s been leading there but going so quietly that you don’t notice something is wrong until it’s way too late,” Barkat said, adding, “Nobody’s going to teach it as a horror story. That’s more of a genre. Unless it’s a genre class, they’re not going to care.”

In recent years the story began to be interpreted as a feminist text, for all women hidden in wallpaper and other confines. Gilman herself wrote it to get the attention of Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a neurologist who treated her in 1887 for depression and charged her “never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again.” Such treatments, known as “the rest cure,” were common at the time for women. They have since been discredited.

“It’s meant to create an argument and bring something to the attention of others, but it’s not an essay,” Barkat said, though she points out that the style of writing is distinctly feminine. “It’s not a male type of writing. It’s the imaginative, emotional writing.”

Still, the story resists all attempts to nail it down. Is it about a Gothic madwoman in the attic? Is it a cautionary tale about ignoring post-partum depression? Is it a ghost story? Is it pure autobiography? Is it a persuasive essay in narrative form? Is the woman in a summer home or a mental institution? Who is Jane? At the end does the woman go crazy or does she set herself free?

Read Barkat’s adaptation, and decide for yourself. Then read it again and change your mind.

Although the story is about yellow wallpaper, the graphic novel contains little color.

“It’s not in color, technically. It’s brown ink,” Barkat said. “It was a challenge for myself. The whole story is about this color, so how do I bring that across without actually using the color yellow? That was an interesting limitation to set, from an artistic standpoint. It was a good choice because then I had to use other things like the patterns, the texture, instead of being able to rely on the color.”

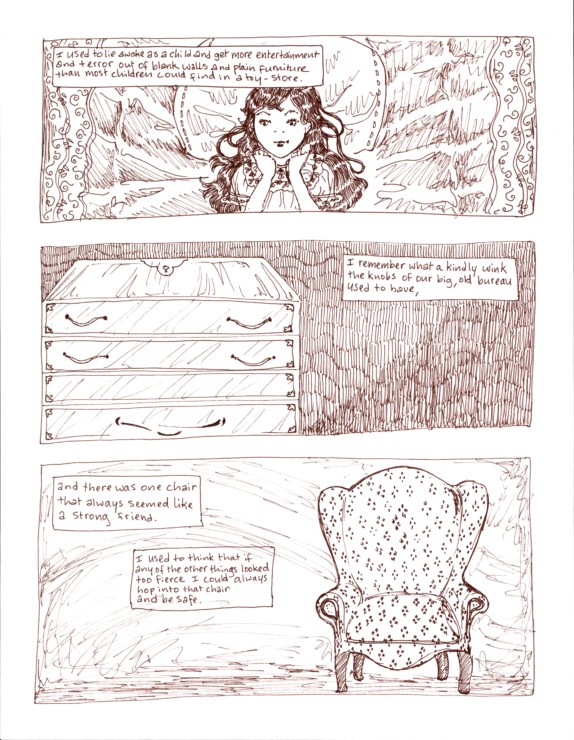

Barkat’s illustrations forced me to notice dialogue and description I’d breezed over in my first read. She says spending time working on the picture that would appear next to the text created a whole different kind of creative experience.

“I was surprised by how robust the image actually is when you sit down to draw it,” she said. “One of the things that struck me was the conversations she had with her husband. The more I drew those panels, everything he’s saying is so carefully calculated in order to dismiss everything she’s trying to get him to understand.”

Barkat also incorporates a variety of art styles into the graphic novel.

“At different points I drew inspiration from certain pictures, like a version of The Nightmare [by Henry Fuseli] in one of the panels,” she said.

One of the sequences I enjoyed occurs when the narrator recalls her childhood:

I used to lie awake as a child and get more entertainment and terror out of blank walls and plain furniture than most children could find in a toy store.

I remember what a kindly wink the knobs of our big, old bureau used to have, and there was one chair that always seemed like a strong friend.

I used to feel that if any of the other things looked too fierce I could always hop into that chair and be safe.”

This narrator is a woman I’d like to have in my writer’s group, a woman who is creative and often funny and who believes “congenial work, with excitement and change, would do [her] good.” It does me good too. Like her, I need my writerly pencil, along with other work, to stay grounded.

The next time my doctor asks if I’m still writing, I could reply that I’ve been writing about my wallpaper and whip out a page from my purse and start reading aloud (even though my house has no wallpaper, yellow or any other color). If I do a good enough job with my words, she might think I’m just a little bit crazy. Then I would know, for certain, that I’m not. Because when we write crazy stories, like Charlotte Perkins Gilman, or draw crazy stories, like Sara Barkat, we’re likely quite sane. And we don’t have to creep over anyone to express what we know to be true.

Photo by Ian Dick, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Megan Willome.

Enjoyed The Yellow Wall-Paper? Browse more by Sara Barkat

- Perspective: The Two, The Only: Calvin and Hobbes - December 16, 2022

- Children’s Book Club: A Very Haunted Christmas - December 9, 2022

- By Heart: ‘The night is darkening round me’ by Emily Brontë - December 2, 2022

Laura Lynn Brown says

Ordered my copy this morning. Thanks for this interview, and a behind-the-pen look at Sara’s considerations in illustrating it. I read it years ago for a class, and then later for myself. It will be interesting to read it again in this format and with these rich imaginings.

Megan Willome says

“Rich imaginings” is exactly right. I’m planning to give it as a gift to the person who introduced me to the story in the first place.

Will Willingham says

Got my copy the other day and it’s fantastic to have in hand. “The story resists all attempts to nail it down,” you noted. These remarkable illustrations serve powerfully to demonstrate just that. The illustrations also defy nail-down-ability and ultimately extend the narrative in new and imaginative ways.

Megan Willome says

Will, I agree, and I think it’s a real accomplishment. In lesser hands, illustrations could nail down the story, tightly, into one interpretation. Sara’s leaves room.

Rebecca J Westberg says

I recently discovered this story and Charlotte Perkins Gilman in a literature anthology. Given the time period and the state of women at that time, I felt deeply moved by the story. As I searched for more commentary online, I discovered Sara Barkat’s illustrated book, which combines my love of a good story and of all kinds of art. Her book is beautifully executed.

Megan Willome says

I agree wholeheartedly, Rebecca. So glad you found your way to the illustrated edition.