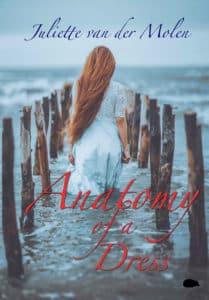

Fashion can be a statement, a trend, a business, an object of fascination, a multi-billion-dollar enterprise, and likely any number of other things. Poet Juliette van der Molen wants to tell what it isn’t, or what it shouldn’t be — the wrapping that turns a woman into an object. The 16 poems of her newly published Anatomy of a Dress are a kind of declaration of independence; in her author’s note, she says that the collection “explores messages sent and interpreted regarding how women have historically been encouraged to dress, mainly for the pleasure and subjugation of the patriarchy.”

When I read that, I took a deep breath, and asked Tweetspeak Poetry’s editor if she was sure she wanted a man, one who is mostly conservative, to review this collection. She said yes, so I took another deep breath, and then took the plunge. So let it be noted at the outset that I’m generally suspicious of any poetry that falls into the category of “message poetry,” whether it’s from the right, center, or left. I’ve read message poetry many times and often enjoyed it or been challenged by it. But I approach it initially with a healthy dose of skepticism, because I don’t know what’s more important here — the message or the craft.

What I have trouble with, I believe, is seeing poetry as a political means to a political end. People can and do write message poetry and political poetry all the time, and particularly these days, but poems have to stand as poems first. To see the phrase “subjugation of the patriarchy” even before the poems begin causes me to frown, my eyes to narrow, and my mind to begin to close.

With that as background, I can say after three readings that the poet should have ditched that part of the author’s note. It wasn’t necessary. The poems tell a story and make the poet’s meaning clear, and they are better than the author’s note led me to believe.

Van der Molen considers different aspects of a dress — zipper, hem, buttons, darts, decorative aspects, pleats, eyelet, neckline, and many others. Who knew there were these many parts of a dress? Certainly not men, other than fashion designers. She calmly and deliberately uses each part of a dress to make a point, perhaps an overall point, that this is not what you think it is, and the person wearing it is the one to decide what that is.

My Hem

the waterline

of marked desire

or intention

it is just

a finished

edge that falls

here

or

there.

it is not

a signal

to send hands

into a

traffic pattern

or to obstruct.

it is not up

for debate

or

for speculation,

it asks

for nothing.

Juliette Van Der Molen

I never knew the hem of a dress could carry such baggage, but I can see how it does. The poem does that by itself. I don’t need someone, including the poet, telling me how I’m supposed to read the poem. That’s not how poetry works. I can see what others have to say, including professional critics. But in the long run, a poem is both a personal act of creation and a personal act of reception and understanding.

Van der Molen is an expat American living in Wales. She has published a chapbook, Death Library: The Exquisite Corpse Collection, and another collection of poetry, Mother May I? Her next collection, Confess: The untold story of Dorothy Good, is scheduled to be published in the fall of 2020. Her work has been published in The Wellington Street Review, Nightingale & Sparrow, Burning House Press, and several other publications. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize (2018) and Best of The Net (2019), and she also serves as editor of Mookychick Magazine.

This short collection called Anatomy of a Dress is a good one. It stands on its own and doesn’t need to be explained.

Photo Fery Indrawan, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

Maureen says

“…subjugation of the patriarchy”? I would say, of women but certainly not of men. (An editor should have caught that.)

How many times I have heard disparaging comments about a woman in a short or tight dress or leggings or a dress cut down to there. Even from other women. Or watched as eyes leer and follow. (Any woman who has ever rode the subway in Rome (I have) or had to walk past a construction site knows the truth of what too often happens.) I think it’s rather brave van der Molen took it on herself to write even 16 poems on the subject. It’s to her credit that, as you write, the poems are better than you thought. It’s unfortunate that that Author’s Note prompted initially a reaction that might bear additional consideration, though I agree with you that a poet should not have to feel impelled to explain her poems.

The interesting thing is, what van der Molen is aiming to get across is that “the messages” are received, uninvited, and not being sent by a woman herself. It would be wonderful to think that in the 21st C no one would think twice about how a woman dresses – or why she’d want to write poems about various aspects of a dress – but that is not the case. Culture and politics both make that so.

I hope a rich conversation arises about this post.

L.L. Barkat says

This is a conversation I’d love to have sitting around a table, partly because I have too many questions (and I know that questions can seem like challenges, when what I want them to be is what they are for me: a true curiosity moment). And partly because the comment box is too small a place to have a big conversation (if one is to not get stuck here all day 😉 )

The questions I have go off in a lot of directions. I wonder, for instance, what makes a poet want to use a poem as a message? I also wonder: is any poem worth its salt not a message of some kind? When I write poems, are they messages? Who am I talking to? What do I hope they will hear, and say in return? Or am I leaving the message at the door as a kind of “notice” (and I don’t want an answer at all)?

Then I wonder… what does it mean for a poem to be political? Is it the message itself? Or does it have to do with a stance that either engages or disengages the reader/hearer, so that a political poem is somehow an act of influence, even power? Is every poem worth its salt somehow political? But what makes some poems feel political and other poems not so much, if by political we mean something about influence and power? And, is there something about poem-ness that makes us not want (or want) a poem to have more or less influence and power?

As for dressing, I have to admit: I believe that how we dress absolutely sends messages, asks things of others (or tells them). When the fashion world spends so very much time trying to hit it right: “this piece of clothing will help you say this about yourself”—I find it scarcely believable that we might wear anything at all and then say it sends no message, tells nothing, asks nothing. Instinctively we know that clothes do invite or repel, place or displace us in a crowd. Human beings use all kinds of signals to communicate, and I do find it a little disingenuous to signal one thing and then not receive the response to the signal or claim we have not been sending signals. This multiplies in complexity when we are crossing cultures, or subcultures.

Personally, I find the act of choosing my “dress” to be more tiresome than fun. The cost involved, the choices, the diversity of crowds I dress to meet, it all feels like more than I have time, interest, or money to consider. I have ended up adopting a bit of a Steve Jobs approach. So has my older daughter. My younger daughter? Every day is new for her, regarding her clothes. They help her envision who she is and then she walks into that and embodies it for the day.

Maureen says

Oh, I love your questions, and your comments.

Maureen says

Does anyone remember the age of the “metrosexual”, a term largely applied to men? (Is it still a thing, so to speak?)

Maureen says

And I appreciate how many positions can be claimed on the subject of any aspect of dress.

That “Steve Jobs look” sends its own message. I wonder if anyone ever counted the number of black t-shirts he washed in a week.

Glynn says

Truth be told, I suspect that men also dress, consciously or not, with a message in mind. Clothes (for men) can suggest formal authority, casual authority, style consciousness (when did men start wearing tan shoes with blue suits and slacks? It was always black shoes with blue suits before), and even some of the same things women’s clothes are noted for. Or, clothes can make a statement about consciousness of what clothes mean, by the wearer donning deliberately un-stylish clothes. Remember the hippies of the 1960s and early 1970s.

I agree that all poems likely have some kind of message — but I prefer to puzzle that out for myself and not be hit over the head with it. It’s almost as if a loud, commanding voice is saying, “This is what this poem is about and you better understand it that way, and if you don’t believe like I do, you are worthless or worse.” This, I think, is what “politics” is degenerating into, and it’s a dangerous state of affairs.

Megan Willome says

I really love the poem you spotlighted here. It makes me think about the hem I am wearing today, the one my daughter would be wearing (if she chooses a skirt or dress today), the hem my mother wore, and my grandmother. Of what those choices say about the stock market today. And how ultimately the hem itself is just a hem, as the poet says.

Sandra Heska King says

Ahem…

I have a skirt I love. It’s 100% polyester but feels like a very light, soft suede. It has a finished hem but also two rows of unfinished fringe that fall below that hem. They swirl around my legs when I walk, fall all askew when I sit. I wonder what that says about me. That I’m still unfinished? I’ve not worn it since living in Florida. It seems more designed for cooler weather, but I haven’t been able to let go of it.

My dress varies from day to day. I’m too easily bored. My hems rise and fall, whether they belong to pants or dresses, though I’m careful that things don’t rise too high below or too low on top. On one hand, I get bored with the same style. On the other hand, a “uniform” would be so much easier.