British writer Ian Sansom has been working on a book about the poet W.H. Auden (1907-1973) for 25 years, and he finally published it. It’s ostensibly about a poem Auden wrote, a poem that Auden himself didn’t like very much. Sansom calls it September 1, 1939: The Biography of a Poem.

I say that it’s “ostensibly” what the book is about. It’s about the poem, and Auden’s life. It’s also about the author, the author’s life, and what happened during those 25 years he didn’t write the book about Auden. It’s literary criticism, too, but this book is unlike any kind of poetry analysis, literary criticism, or biography that I’ve ever read. I don’t think I can tell you what that difference is, but I can show you.

*

*

We know what happened on September 1, 1939. Nazi Germany invaded Poland, prompting France and Britain to declare war. Poland was the first “blitzkrieg,” a lightning war that sent tanks, armored cars, and bomber planes across the border. Both military and civilian targets were bombed. Within the first few days of the attack, Polish Jews found themselves shot, rounded up, and persecuted. The Holocaust was about to begin.

*

Seeing what was coming, Auden and Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986) left England in early 1939, landing in New York. When the war started, Auden’s friends and admirers were surprised that he didn’t return. Instead, he stayed in New York City, sitting out the war and not going back until it was all over. He did write a poem, though: “September 1, 1939.”

*

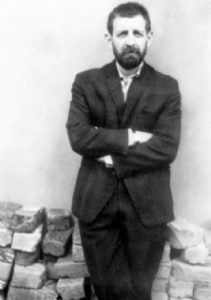

W. H. Auden in 1939

That sounds a bit snarky. His friends in England faced the blitz, and he wrote a poem.

*

Sansom notes that each stanza is a complete sentence. A bit long, perhaps, but complete. Auden situates himself writing the poem in “one of the dives / on Fifty-second street,” which Sansom identifies as a then-illegal-but-mostly-tolerated gay bar.

*

While Sansom is bringing his reading, research, and analysis to a very sharp point, you’re left with a distinctly unfavorable view of Auden. His friends and countrymen are facing invasion and possible annihilation, and he’s sitting the whole thing out in a bar in Manhattan. Sansom reads what he’s written to this point to his wife, and she asks him if he has seriously spent all those pages on the first two words of the poem, “I sit.”

*

He did. I’m not making this up. I was growing concerned myself.

*

Spouses can be like that. Fortunately for the book, the reader, and his marriage, Sansom speeds things up, and does a quite masterful job of analyzing each stanza. He includes a list of the books on Auden and his era he’s read during the past 25 years, and it is literally in the hundreds.

*

I didn’t actually count the number of books. But it’s a lot.

*

Ian Sansom

Sansom, a reviewer for The Guardian and a freelance writer, has published several mystery novels, including The Norfolk Mystery, Death in Devon, The Case of the Missing Books, Mr. Dixon Disappears, The Delegates’ Choice, Westmoreland Alone, and Essex Poison.

*

As it turns out, Auden was an avid fan of mystery stories. So was T.S. Eliot. And that may be a point of connection between Sansom and Auden. But he doesn’t talk about it much.

*

Sansom has published other works, too. His novels include Ring Road and The Impartial Recorder. His nonfiction books include Paper: An Elegy and The Truth About Babies from A-Z. (Now we have part of the reason why the book on Auden was put off for so long; Sansom and his wife were rearing a family.) (It’s one of the reasons I didn’t started writing novels until my youngest was almost out of high school.)

*

‘September 1, 1939” is one of Auden’s most famous poems. But Sansom sees the flaws. It is, he writes, “a poem that desperately wants to be right, and which occasionally gets things desperately wrong.”

*

September 1, 1939: The Biography of a Poem is a stunning book. I almost couldn’t stop reading it, just to see where the narrative was going to go. Sansom clearly likes and admires Auden’s poetry, but he doesn’t allow admiration to deter him from doing a marvelous job of criticism.

Photo by Michael Leckman, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Katie says

“Sansom clearly likes and admires Auden’s poetry, but he doesn’t allow admiration to deter him from doing a marvelous job of criticism.”

This statement has bolstered my courage enough that I ask the following:

Glynn,

Once again you have piqued my interest in a book with your thoughtful comments on the work.

Please know that I do not make this comment, or rather, ask this question without serious respect for your writing. I do not mean it as a critique or judgment by any means.

I have one question (that I honestly ask with some trepidation, but also with a genuine desire to understand your choice of wording):

You write: Within the first few days of the attack, Polish Jews found themselves shot, rounded up, and persecuted.”

then you write: “The Holocaust was about to begin.”

My question is this: Why didn’t you say: “The Holocaust had begun.” ?

Respectfully,

Katie

Glynn says

Katie, likely because I associate the Holocaust with the death camps. Germany had already set up concentration camps inside Germany for various people, including but not limited to Jewish people. They were prison camps, compared to the systematic death camps that came after the Wansee Conference near Potsdam in 1942 – when the “final solution” was approved for implementation. Years ago, I read a book about the whole period called “The War Against the Jews 1933-1945” by Lucy Davidson that put the start with Hitler’s coming to power. Another possible starting point might be Kristallnacht, Nov. 11, 1938. When the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, it wasn’t only Jews who were singled out.

Katie says

Glynn,

Thank you for your answer.

This makes perfect sense.

I appreciate your response.

Katie

Laurie Klein says

I’m intrigued! I’m going to wade into Samson waters. I’m on my way next to our library site, eager to check out one of Samson’s mysteries. You often inspire my reading list. Thanks, Glynn.

Peter Krynicki says

September 1, 1939. It’s almost inconceivable to me that there is not one reference to Hemingway in this book. The obvious reference would be the drinking, but more significantly, and just to mention one, “… the purpose of all great literature is to familiarlize characters with defeat.” Frederic Henry? Robert Jordan? The Snows of Kilimanjaro?