Poet Mary Oliver died last January at age 83. What do you say about a poet who won the Pulitzer Prize (American Primitive, 1983), the National Book Award (New and Selected Poems, 1992), and a Guggenheim Fellowship; was given a fistful of honorary doctorates, and was a bestselling poet for most of her life? She published 33 poetry collections and four nonfiction or essay collections, and was recognized as one of the best nature poets ever. And she was one of those rare poets whose work brought affirmation from critics and the general public alike.

You can say a lot of things, but it might be best simply to recognize her for the eminence in the poetry world she was and be done with it. And yet that seems too abrupt.

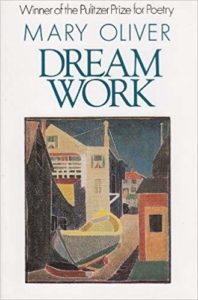

I went looking for one of her works to read and discuss. I passed by the award winners and instead settled on Dream Work, the collection she published after winning the Pulitzer Prize. That first post-award collection would be a challenge for any poet; expectations would be high and the critical knives might be out if it doesn’t seem to measure up.

It measures up. If anything, it drew even more critical praise than American Primitive did.

Dream Work includes 45 poems. At first glance, it seems largely a collection of poetry about nature and the natural world. And certainly those subjects and themes dominate the volume—she has poems on everything on dogfish, trilliums, starfish, turtles, milkweed, black snakes, moths and more. This poem is a good example of the deep observation and detailed eye she brought to her nature poems.

Marsh Hawks

just above the rough plush

of the marshlands,

as though on leashes,

long-tailed and with

yard-wide wings

tipped upward, like

dark Vs; then they suddenly fall

in response to their wish,

which is always the same—

to succeed again and again.

What they eat

is neither fruit nor grain,

what they cry out

is sharper than a sharp word.

At night they don’t exist, except

in our dreams, where they fly

like made things, unleashed

and endlessly hungry.

But in the day

they are always there gliding

and when they descend to the marsh

they are swift, and then so quiet

they could be anything—

a rock, an uprise of earth,

a scrap of fallen tree,

a patch of flowers

casting their whirling shadow.

Mary Oliver

My favorite word in the poem isn’t a word at all—“uprise,” a word that fits perfectly and brings to mind exactly what it intends. It’s one of the beautiful images she includes. The imagery is so vivid that you know you’re standing with her, watching those hawks with their “yard-wide” wings, tipping upward and suddenly falling.

Dream Work also includes other kinds of poems, poems that hint at the difficult life she lived as a child, and how she took refuge in the woods. There are poems about rage and whispers, about the need to leave and save her own life, and about her father showing up as a visitor. Mixed in as they are with the nature poems, these poems don’t seem out of place. For Oliver, the personal is the natural; nature is a refuge and an escape.

We had Mary Oliver for a time, and we are blessed that we did. She took us on walks with her into the woods, on the beach, and across hills, and then stopped us so we could look up and try to count the stars in the night sky. She showed us how to employ nature to come to terms with where we come from, and to point where we might be going.

Photo by Rick Seidel, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

Diane Stephenson says

I am not familiar with Mary Oliver, but you have brought her to life for me in this post. Thank you for sharing.

Glynn says

Thanks for commenting, Diane.

Diane Stephenson says

You are most welcome, Glynn.