I’m reading Your Daughter’s Country, the recent poetry collection by the Missouri-based poet John Dorsey, and I’m thinking to myself that I wouldn’t want to be the subject of one of his poems. He casts an affectionate eye on his friends, acquaintances, and relatives, but it is a ruthlessly honest eye, one that sees them as they are—the good in them, the bad, the indifferent. You don’t read a poem with the title of “Coco Malone is a Bad Bitch” and expect both scalpel-like description and affection, but that’s what you get.

I’m put in mind of my Uncle Revis. He was my father’s brother-in-law, the husband of a beloved aunt who made the best biscuits in north Louisiana. If the word “garrulous” hadn’t already existed, it would have been invented just for him. For years, I spent a summer week or two with my grandmother, who lived across the street from my aunt and uncle, and we ate together, picked vegetables together (my job was digging for potatoes), and watched television together. Saturday nights meant The Lawrence Welk Show, and my Uncle Revis would sit quietly until the Lennon Sisters performed, when he would start shouting, “They’re ignorant!” at the television. It was something you got used to.

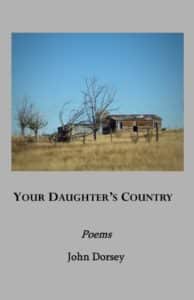

John Dorsey

He was a voracious reader, and he introduced me to James Michener and many other writers. He always smelled like pipe tobacco, and he was forever playing with his pipe and occasionally smoking it. And he raged about the next-door neighbor’s cats, of which there were many. Early one Saturday evening, we sat on his back steps as he contentedly told me stories and smoked his pipe. And then he tensed and told me to keep very quiet and still. He lifted his rifle (we always sat on the back steps with his rifle at hand), took careful aim, and then shot the cat that had dared to jump the fence into his yard. That the neighbors were his oldest son’s in-laws didn’t seem to matter. Or perhaps that was the point.

My Uncle Revis would be a character in a John Dorsey poem.

Dorsey tells stories about the people he knows and loves. He writes about grandparents, cousins, friends, the parents of friends, aunts and uncles. He writes about their pets, the towns where they lived, their work, their dreams, their tragedies, and what happens in their lives. The title poem is about his great-grandfather, who had already fathered 12 children when he met Dorsey’s great-grandmother and fathered more, although a few looked like the mailman, the milkman, and the trash collector, “any one of them made for better company / on a cold night.”

He also writes about his people’s music—the music they listen to and the music they sometimes become.

Walking After Midnight in Linn, Missouri

& the jukebox that once offered

a youthful kiss from patsy cline in the moonlight

is now drowned out by the bartender

talking about how the fry cook

is not her boyfriend

sleepy eyed construction workers

are left to dream about true love

on their own as they wander back out

into the cold

their regrets will haunt them

long after the grease

from the fried chicken special

has settled in their stomachs

settling is just the way of things

nobody is searching for anyone

after midnight here

pride only makes you lonely

while the rest of the world

is fast asleep.

Dorsey is the author of some 50 books of poetry and chapbooks, including Being the Fire (2016) and Shoot the Messenger (2017). His work has appeared in more than 2,000 magazines and anthologies around the world. He is a founder and co-editor of The Gasconade Review. He lives in Belle, Missouri.

You don’t expect a contemporary book of poetry to take you back decades to your childhood, but that’s what Your Daughter’s Country did for me. It might remind you of the people who shaped your life, the people who were known to be “characters” in your family, and that families were dysfunctional long before the word “dysfunctional” was even known. And yet there is still affection, and love, and a sense of thankfulness for having known them.

Related:

John Dorsey reads “The Alligator Man”

Patsy Cline sings “Walkin’ After Midnight”

Photo by Paulius Malinovskis, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- 10 Great Resources for Teaching the Civil War - March 6, 2025

- Relearning Civil War History to Write a Novel - March 4, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Marjorie Maddox and “Seeing Things” - February 27, 2025

Megan Willome says

Glynn, I really like how reading this collection made you think of one of your own relatives, wondering how he might have been rendered, had John Dorsey gotten a hold of him.

I’m a big fan of storytelling and poetry that looks at people with ruthless honesty and sincere affection. It’s the kind of balance we’re most likely to give to family members, I think.

Laura Lynn Brown says

The line about sleepy-eyed construction workers reminds me of the day (many decades ago) when some of my dad’s bricklayer cousins came to help him lay the cinderblock walls for a garage addition to the house. Lots of “Yo!” and “Ho!”

I’m glad for that video of him reading. His delivery of the poems is so different from his introduction of them — more embodied, for one thing.