You begin your life in a provincial capital. When you’re three years old, the country’s leader attacks your city, which is the “wrong” variation of your region’s and family’s faith. The family debates: leave or stay? The brutality of the ruling regime makes the decision: leave. The next four years of your life are spent in a refugee camp, until the family is granted asylum in a new country. The family is safe; it’s survived. But you’re now a stranger in a strange land, with a new language, a new culture, and a new society. The predominant skin color is not the same as yours.

At some point in your young life, you will begin to write poems like this one.

Cultural Chimera

speak two languages

a refugee

of two places

struggling with being

the wrong ethnicity

twice over—

in the eyes of my roots

and where I am asked

to bury them

torn

between east and west

sun and moon

an eclipse

that doesn’t get to witness

the magic of its being

resisting against the image

of supposed impossibility,

delaying its birth furthermore

the unity of two

without conflict

an omen

that even in darkness

miracles are born

The poet is Ali Nuri, a young man who works in the IT industry in Las Vegas and who writes poetry to make sense of his life and experiences. He was 3 when Sunni Muslim Saddam Hussein attacked Nuri’s Shi’a-Muslim hometown in Iraq; he and his family spent the next four years in a refugee camp in Saudi Arabia until emigrating to the United States. The family moved often – Pennsylvania, Michigan, Indiana. That Nuri was dyslexic didn’t help his adjustment. What did help was the online world of writers. He would grow up to earn a degree in urban planning and become a poet, an author, and an artist.

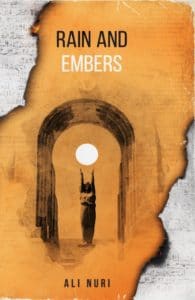

His poetry collection Rain and Embers reads almost like a journey. The poems, like “Cultural Chimera” above, reflect tensions — the general tension of all emigrants arriving in a new land, and the specific tension of an Iraqi Muslim in a non-Muslim country, when what the poet remembers of his birthplace is rain — the napalm rain that pours from airplanes (and thus the collection’s title). It’s also an individual tension —the feeling of being different, the trouble of learning to read and speak in a new language, the sense that being of two countries means being of no country.

The poems cover a broad range of subjects: family, homeland, emigration, people, relationships, art, and more. There are even poems relating to a specific color — Pantone 448C, a muddy brown said to be the ugliest color in the spectrum. Nuri considers that Pantone 448C is the color of his skin, and he wonders what color God is.

Some poetry collections charm the reader; others can chill the reader. And then there are collections like Rain and Embers, which ask you to travel along on a journey of fleeing death and destruction, living in refugee camps that often belie the name, and arriving in an alien land that offers physical safety but often demands that you change who you are. And you’re not sure what you’re supposed to be changing from.

Photo by SMcD22, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Essays: Benjamin Myers Takes on Ambiguity and Belonging - February 4, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Louis MacNeice and “Autumn Journal” - January 30, 2025

- “What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt” - January 28, 2025

Maureen says

The youngest (8 at the time) in the Iraqi family I worked with on arrival to the States asked his father, ‘Is Iraq my country, or is America my country?’ His wise father said, ‘They both are.’ I have never forgotten that. The family spent two years trying to get out of Iraq when the life of the father, who worked with the U.S. and was responsible for security matters, was threatened. When the ‘go’ came, they had to leave immediately, go to Turkey, and then fly to Dulles. What they carried? What they could put in their individual suitcase. Not at the family got out. Left behind: mother (who later died), brothers (one of whom subsequently was killed), other relatives, and so much more. Fortunately, they arrived before the current administration came into power. Knowing the family (they ‘adopted’ me) is one of the greatest joys of my life.

Many (I want to say, most) Americans have no idea what immigrants suffer to come here, what they have to give up, what they have to do to ‘be American’. Books like Ali Nuri’s are important, because they give voice both to the awfulness and small joys that these immigrants experience. Imagine contemplating the color of your skin, aware that it’s ‘said to be the ugliest’ in the color spectrum!

Maureen says

I meant to write, Not all the family….’

Ali Nuri says

Maureen, thank you for sharing that story, it is truly haunting but it makes those of us with similar experiences feel less isolated and alone.

Maureen says

Thank you, Ali, for sharing your voice and for responding here.

The cover of your book is beautiful.

I’d love to know more about your art. (I write an art column and collect.) I’ll go visit your Website.

Kate says

I don’t know where to begin, your insight is incredible, the way you unearthed the connections is truly profound.

Katie says

Pantone 448C

“Said to be the ugliest color in the spectrum”

Says who?

Who gets to say that color – (muddy brown)

or any color is ugly?

Who gets to be a color Nazi?

Shouldn’t color be about as subjective as it gets?

I like blue, you like _____, he likes gray, she likes purple, . . .

Who gets to tell me or you or anyone what color is ugly?

I say: no one.

I don’t know what color God is,

just that He made colors

and loves them all.