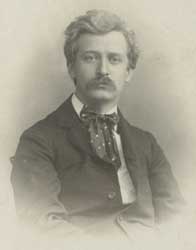

Horace Traubel (1858-1919) is not a name we immediately associate with Walt Whitman (1819-1892), but it is thanks to Traubel that we know as much about Whitman as we do.

Traubel’s father had emigrated from Germany; his mother was also of German extraction. He was born in 1858, the fifth of seven children. He became a paper boy at 12, and also worked in the printing business and as a cub reporter.

Horace Traubel

He met Whitman when he was 14, when Whitman was living with his mother and brother in Camden. They became friends. Traubel became interested in literary pursuits, publishing his own poetry and literary criticism. He published a literary magazine for a time, associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, and was also a founder of The Worker, a weekly socialist newspaper (Whitman, despite their friendship, never cared for Traubel’s socialist beliefs). Traubel was well known to Eugene Debs, Upton Sinclair, and other leading socialists of the day.

What Traubel is most remembered for, however, is his literary relationship with Whitman. For four years, as Whitman’s health gradually declined, Traubel spent considerable time with the poet, serving as a kind of literary secretary and writing down everything and anything Whitman wanted to say. What resulted is a treasure trove for biographers and literary historians. It’s also safe to say that few others have read the entirety of what Traubel produced.

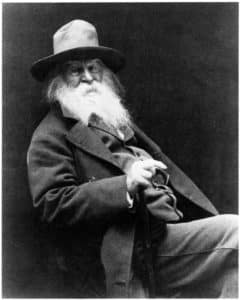

Walt Whitman

Nine volumes were eventually published, three during Traubel’s lifetime; critics were not encouraging. Volume 4 was published in 1953, Volume 5 in 1964, Volume 6 in 1982, and Volume 7 in 1992. The last two volumes were published in 1996. The volumes are large; Whitman was invariably talkative, and Traubel wrote everything down.

“But the fact remains that the material begs for compression,” writes Brenda Wineapple, author of several books on the 19th century and the editor of just such a compression, Walt Whitman Speaks: His Final Thoughts on Life, Writing, Spirituality, and the Promise of America. “The nine bulky volumes of Traubel’s transcriptions are cumbersome, redundant, and taxing even for the most ardent Whitman admirer. As a result, the material is neither well-known nor easily accessible.”

Wineapple’s compression is a small, slender volume of 196 pages, published by the Library of America. It’s arranged much like a book of quotations, except the quotations are also accompanied by observations, meditations, reflections, opinions, and idle thoughts. The subjects are broad; Whitman had an opinion on just about everything.

Here is a brief sample of Whitman’s thoughts included by Wineapple.

On James Boswell, the biographer of Samuel Johnson: “The more I see of the book (Life of Johnson) the more I realize what a roaring bull the Doctor was and what a braying ass Boswell was.”

On Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Emerson’s face always seemed to me so clean—as if God had just washed it off. When you look at Emerson it never occurred to you that there could be any villainies in the world.”

Brenda Wineapple

On Leaves of Grass: “Leaves of Grass is an iconoclasm, it starts out to shatter the idols of porcelain worshipped by the average poets of our age—not ruthlessly—not wantonly—but to do it seriously, as having a great purpose imposed.”

On America: “I look ahead seeing for America a bad day—a dark if not stormy day—in which this policy, this restriction, this attempt to draw a line against free speech, free printing, free assembly, will become a weapon of menace to our future.”

On Lincoln: “The radical element in Lincoln was sadness bordering on melancholy, touched by a philosophy, and that philosophy touched again by a humor, which saved him from the logical wreck of his powers.”

The compression (especially of nine fat volumes) represented by Walt Whitman Speaks works exactly as intended. Few of us would likely read the entire mass of statements and observations, but this representative sampling provides an excellent insight into the final thoughts of the man considered America’s poet. We owe a debt to Horace Traubel for taking it all down, and to Brenda Wineapple for summarizing it.

Related:

Longfellow, Whitman, Wheatley: Whatever Happened to Patriotic Poems?

Walt Whitman in Brooklyn: Newspapers and “Leaves of Grass”

Using Poetry to Reflect Upon the Civil War – Part 3: Walt Whitman

Photo by Lee Cullivan, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Forrest Gander and “Mojave Ghost” - March 27, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

That quote on Lincoln is just so fun. Also, it has a touch of “poet’s power” in it. 🙂