Tony Hoagland and the Body

The very first time someone shared a poem with me about a body I ran, not walked, down the hall to the restroom and took a knee before the porcelain throne. I thought poems were about flowers, trees, the occasional large ship. I was unaccustomed to the presence of a body there amongst the words. The poem, which made a lasting impression despite my inability to recite the actual words containing the body to you now, was not vulgar. It wasn’t about my body, nor possibly even the poet’s body.

But, there was a body, encapsulated in the poem, all the same. And the problem, if we wanted to decide that’s what it was, was that I felt the poem in my body. And that sent me racing to the restroom.

I sent a message back to the person with a note saying I had not expected the poem to be so corporeal. (I couldn’t even use the word body to explain my very physical reaction.)

It seems, now that I have been conditioned to expect things other than trees and flowers (the occasional ship, mind you, can still have that unexpected corporeal sensation), I can read poems with a certain physicality to them without asking the teacher for a lavatory pass. And it is, perhaps, that very quality (amongst so many others) that makes reading Tony Hoagland’s poems the impressive experience that it is.

Take the opening of “Honda Pavarotti” from the Donkey Gospel collection:

I’m driving on the dark highway

when the opera singer on the radio

opens his great mouth

and the whole car plunges down the canyon of his throat.

So the night becomes an aria of stars and exit signs

as I steer through the galleries

of one dilated Italian syllable

after another.

I can’t read this without following that car down the esophageal abyss, and while the initial sensation of careening into a dark, wet tunnel past the singer’s deviated uvula seems a bit terrifying at first, by the time we’ve passed by various other bodily descriptions (and an operatic climax) we hear him say “And this dark and soaring fact / is enough to make me renounce the whole world // or fall in love with it forever.”

Reading Hoagland has helped bring me to a place where I have discovered a new way of relating to the words that once caused tremors, of encountering such words as friends. His poem “Dickhead” becomes one of those poems that explains me to myself, opening with

To whomever taught me the word dickhead,

I owe a debt of thanks.

It gave me a way of being in the world of men

when I most needed one,

He goes on to tell of being the “pale and scrawny” adolescent, ill-fitting in the world and trying to survive

the savage

universe of puberty, where wild

jockstraps flew across the steamy

skies of locker rooms

and everybody fell down laughing

at jokes I didn’t understand

Until, that is, he discovered the word — a malediction, really — that would in irony’s amusingly twisted way, become a thing that “protected me and calmed me like a psalm.” He found that “dickhead this and dickhead that” became a song he could sing and calm himself in the face of a frightening world around him.

This week while I’m reading Hoagland I’m traveling, as I’ve been doing for too many of the last few weeks, so I am holed up in the club lounge of a tall hotel with Rachael Ray carrying on in the background about cooking something previously unimaginable, on the television suspended above packaged granola bars and a large silver bowl of what was, once, I’m sure, fresh fruit. From my perch, I’m thinking about how I don’t have the same relationship to manhood and being in the world of men that Hoagland had, but even so have just as much a need for a particular word to give me a way of being there. I did miss out on “the steamy skies of locker rooms,” and still, I have my own sort of pubescent savage universe to navigate, seemingly all over again. Poems, perhaps more especially now the ones that talk about bodies, have the means to calm and they make me grateful, like Hoagland, “for the lives I / never have to live again.” He concludes:

I recall when flesh

was what I hated, feared

and was excluded from:

Hardly knowing what I did,

or what would become of it,

I made a word my friend.

* * *

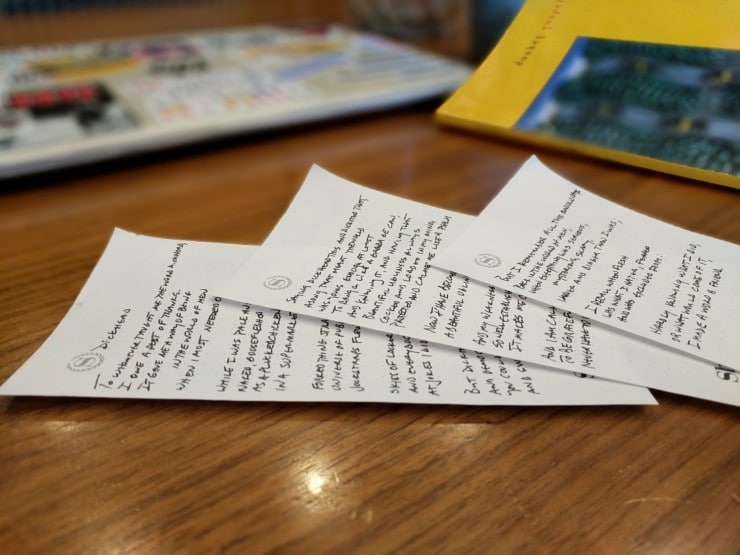

As is Tweetspeak’s tradition, we invite you to a group poetry dare for the month, this year reading a favorite poet all month, and writing poems out on paper. Perhaps you’d even enjoy making a collage of pictures and phrases cut out from magazines in response to a poem. Each week I’ll share what I’ve read, and hope to see what you’ve been reading as well.

“Dickhead” by Tony Hoagland (excerpt)

and I am calm enough

to be grateful for the lives I

never have to live again;

Featured photo by Nathalie, Creative Commons license via Flickr. Post by Will Willingham.

Browse more Tony Hoagland

Browse poets and poems

Explore Adjustments by Will Willingham

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

L.L. Barkat says

Thank you for this post and its depths. I find myself not wanting to interrupt its own flow and perfection. I find myself wanting to almost meditate upon it. (Even with some of the strong images, this is how I find myself. 🙂 )

I really like this from Hoagland’s poem:

“Hardly knowing what I did,

or what would become of it,

I made a word my friend.”

And I like that though you don’t seem to have found a single word the way he did, you’ve found a genre (poetry)—which one could also say Hoagland found. Words do have such remarkable power. It’s good when they are on our side as friends.

Will Willingham says

It’s true, as you seem to suggest in the last of your comments, that words can also become something other than friend. It is good, I think, to have made friends with many of them in order that those rogue other words might lose some of their force. 🙂

Bethany says

I’m ruminating on this idea of reading a favorite poet all month and responding to it in some way. It’s a wonderful thing to find a poet who sings in your key. Typically, I go with Kooser, but I’ve gone through some shifts lately and am wondering where it will land me (or with who, rather). 🙂

Will Willingham says

Kooser is always a good choice. Wondering who you landed with this month in the end. 🙂

Bethany says

or with *whom 😉

Laura Brown says

In the late 1980s, sometime before the ’88 presidential election, I heard a group of teenage boys in a shopping mall gleefully mock-taunting one another with the word “Dukakis.” Savoring the sound of it, delighting in their appropriation of a funny name, cracking themselves up, bonding as bros, feeling the freedom of saying it out loud (with a loud emphasis on the middle syllable) — a name conveying so many things they otherwise probably couldn’t have even found the words for, let alone dared to say.

At the risk of driving this into a discordant abyss, I wonder if this is one of the purposes of cusswords, especially corporeal cusswords. And what kind of self-explaining and body-accepting work small children might be doing when they make friends with a word during the creative phase of generating butt jokes.

Will Willingham says

Dukakis. Lol. 😉

I think there is a place for it, especially during our most formative years. Which is why I think they still have to be considered cusswords, and not just fully welcomed into the the realm of polite parlor conversation. I mean, if they are not seen in some way as inappropriate, they lose some of that power.

Mary Van Denend says

You pose a great question here, Laura. It made me think of a family story we still laugh about.

When my kids were very young we lived on the coast of Maine near a small harbor, where a crusty old fisherman would walk by our house every morning on his way to piddle around on his boat. If the kids were in the yard he’d yell out at my boys, “What are you up to, you two towheads?” Our 3 yr old daughter, who was younger, secretly adopted this word “towheads”, not knowing its meaning at all. One day when the brothers were chasing and teasing her she’d had enough. She jumped into the open playpen for safety and said, “Stop it, you idiot towheads!” This must have sounded like a terrific swear word to her, and combined with “idiot”, she was delivering a blow.

Will Willingham says

I recall in a moment of utter frustration with one of my siblings as a kid I threw out a particular slur. At the time, I thought I made up the word. I didn’t recall ever having heard it before. And of course I coupled it with an absurd image that only made sense coming from a little kid’s mouth. My brother was aghast that I would use such a word (he knew what it meant) that it stopped him in his tracks from his continued harassment and compelled him to have a rational conversation with me about using words I didn’t understand, etc.

Sandra Heska King says

I’m with Laura. I need to sit with this piece for a bit.

The first time I ever heard the word “douchebag” was when I saw E.T. in my 40s. Seriously. Then there was “Uranus.. Get it” Your anus?”

I still love that movie.

Will Willingham says

Okay, that one I could live without. But the E.T. joke was priceless. 🙂