I have a personal definition of what makes a good biography. Solid research and an understanding of the subject are a given, but what separates exceptional biographies from good ones is whether I find myself believing that I’m there with the subject, living the scenes, and experiencing the trials and triumphs. A simpler way to say it is this: Do I identify with the story being told about this person’s life?

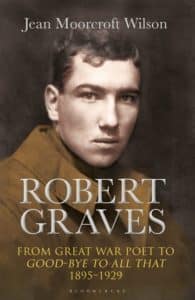

Robert Graves: From Great War Poet to Good-Bye to All That 1895-1929 by Jean Moorcroft Wilson is one of those exceptional biographies. Almost all I knew about Graves was that he was the author of I Claudius and Claudius the God, written in the 1930s and popularized on PBS in the 1970s. Derek Jacobi starred in the title role. I was so mesmerized by the TV series that I read both books, learning that Graves had based his fictionalized story on the gossipy account by the Roman historian Suetonius in The Lives of the Caesars.

This first volume of a planned two-volume biography allowed me to see the man not only in the context of World War I poetry but also in the decade that followed the war. And it confirmed my vague perception that Graves stood apart from his fellow war poets; he wanted it that way and took pains to suppress a lot of his own war poetry. He was so successful that quite a few of his poems were published only after his death.

Robert von Ranke Graves (1895-1985) was the son of a British father and a German mother. His upbringing was conventional middle class. Alfred, his father, was the literary figure in the family, and Amy, his mother, was the religious figure. Both were significant influences on Graves, and both likely played a role in how his initial prudish nature gave way to an unconventional lifestyle after he married. Wilson spends considerable effort on what she sees as Graves’ conflicted sexuality, until he embraced conventional marriage after meeting Nancy Nicholson. Yet theirs was not so conventional; Nicholson believed so strongly in the rights of women that she kept her maiden name after marriage and insisted that their daughters carry her last name.

Like so many other poets and writers, Graves and his poetry were transformed by World War I. Wilson points out that even previously published poets like Graves had a horribly difficult time finding the right language to describe the scenes and events of the war. Yet the war evoked an outpouring of verse across the spectrum of British society; Wilson notes that poet and writer Edmund Blunden said that Britain had been transformed from a nation of shopkeepers to a nation of poets.

Graves was seriously wounded in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, returning to England to recover. While he continued to serve in the army, he did not return to the front. For many years he suffered from what today is called post-traumatic stress disorder, and small reminders could quickly push his mind back to the battlefield.

Jean Moorcroft Wilson

Following the war and his marriage (with four children arriving in quick succession), Graves embraced a lifestyle that was unconventional even for the 1920s. He had met the American poet and writer Laura Riding, and she became part of the Graves family, even with Nancy Nicholson’s initial approval. Riding would exert an almost controlling influence on Graves well into the 1930s, as his literary career grew and soared and hers stagnated. He would eventually leave his wife and family and simply live with Riding.

Wilson brings in-depth familiarity with World War I poetry and poets to her subject. She’s written biographies of other war poets, including Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon, Charles Sorley, and Edward Thomas, as well as studies of Virginia Woolf and the London she lived in. She is a lecturer in English at Birkbeck, University of London, located in Bloomsbury. Her understanding of the war, the poetry it produced, and the British literary scene of the 1920s informs virtually every page of the Graves biography. And it seems that Graves knew (and often rejected) such literary stars as T.S. Eliot, Siegfried Sassoon, T.E. Lawrence, Edith Sitwell, Thomas Hardy, Virginia Woolf, the American John Crowe Ransom, and many others.

Robert Graves is an outstanding literary biography, treating the poet with both sympathy and dispassionate understanding. Wilson doesn’t make excuses for how he often treated people, including his own family. She notes that he was likely the best loved poet of the 20th century. And she has us walk in the poet’s shoes, sometimes celebrating with him and sometimes cringing at his actions and attitudes. She tells his story very well indeed.

Related:

Brian Gardner’s Up the Line to Death: The War Poets 1914-1918

Siegfried Sassoon and The War Poems

The Most Famous Poem of World War I

The Poems the Soldiers Read in World War I

The World War I Poets in the War

Photo by Greg Westfall, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young,author of Poetry at Work and the novels Dancing Priest, A Light Shining, Dancing King, and the recently published Dancing Prophet.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

L.L. Barkat says

Fascinating background, Glynn. 🙂

And can I just say?—that photo, oh, that photo of woodlands. I love it.